James Leggio

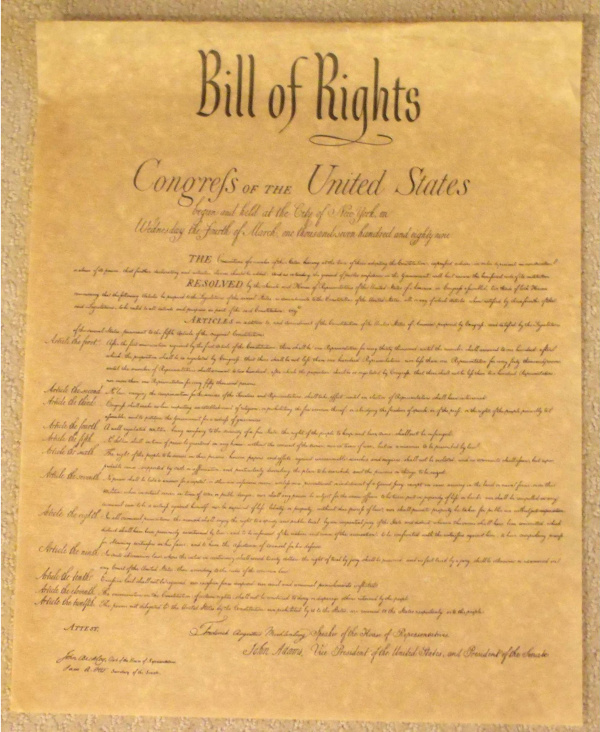

Like the King James Bible, the United States Constitution contains a number of lofty-sounding but ambiguous sentences whose word choices, syntax, intent, and conceptual frame of reference remain problematic — and therefore prone to misreading. The Second Amendment is one of these passages. It reads:

A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.

The disputed meaning of a key phrase — “a well regulated Militia” — goes to the heart of the gun debate that now bitterly divides citizens across the country. Gun-rights activists take the Amendment to mean that “the people” in general have an indisputable right to bear firearms as they see fit, asserting unfettered use for recreation, self-protection, and even self-expression.

And yet this phrase’s meaning was in fact quite otherwise, and clearly so, to those who waged the American Revolution and subsequently wrote the Constitution. As Patrick J. Charles has written in his book The Second Amendment: The Intent and Its Interpretation by the States and the Supreme Court (2009) and in a series of articles including “The 1792 National Militia Act, the Second Amendment, and Individual Militia Rights: A Legal and Historical Perspective” (2011):

Unfortunately, this [the gun-rights activists’] argument would fail were a court to fully investigate what constituted the Second Amendment’s “well-regulated militia” as the Founders understood it. The right to “keep and bear arms” in a “well-regulated militia” was not a license to individually train or discharge firearms. What constituted a “well-regulated militia” was a carefully planned constitutional military force controlled by the State and federal government.

No random, freelance shooting of firearms was authorized by the Amendment, despite some contrary claims made today. Instead, legitimate use of arms took place within a militia: a properly trained, organized, and officered military unit answering to the lawful government through the authorized command structure.

Indeed, the United States Militia Act, as signed by George Washington on May 8, 1792, includes this very specific definition of what “well regulated” was taken to mean at the time:

Sec. 7. And be it further enacted, That the rules of discipline, approved and established by Congress, in their resolution of the twenty-ninth of March, 1779, shall be the rules of discipline to be observed by the militias throughout the United States …

And this is where Baron von Steuben comes in. The document cited here in the Militia Act as the official “rules of discipline, approved and established by Congress” is in fact Regulations for the Order and Discipline of the Troops of the United States, the elaborate set of regulations written by Steuben, with Washington’s authorization, during the throes of the Revolution and officially approved by Congress on March 29, 1779. Ultimately Steuben’s military-training drill manual did much to create an army capable of winning independence for the new nation.

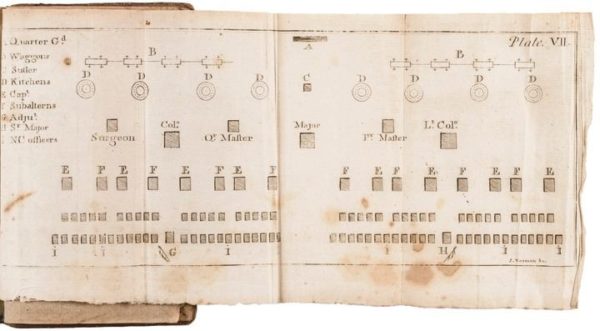

Baron von Steuben codified the practical, working definition of “a well regulated Militia” in his Regulations. The book version of Regulations printed in 1794 therefore contained, as an appendix, the Militia Act of 1792, which had explicitly pointed back to Steuben’s manual as authoritative. Taken together, the Militia Act and the Regulations clarify the Revolutionaries’ understanding of what a militia was, how its training regulations worked, and how its deployment of armaments fit into the overall government structure framed by the Constitution (ratified in 1788) and the Bill of Rights, with its Second Amendment (ratified in 1791 — the year before the Militia Act).

The Regulations and the Act were all about specifics, some of which are lost on us today in vastly different times. For example, one important issue in weapons training concerned ensuring uniformity of firearms. The Founders wrote the Second Amendment to grant “the people” the right to “keep and bear arms” precisely so that citizens could serve in a militia in which they had to provide their own firearms, gathered from hither and yon. Recruits to the Continental Army might muster with a chaotic array of different arms, including but not limited to the familiar British “Brown Bess” smooth-bore flintlock musket, captured from the enemy; the “Charleville” musket, purchased in quantity from the French; muskets of every description made by local gunsmiths; and the grooved-barrel American long rifle, also known as the “Pennsylvania” or “Kentucky” rifle, made for game hunting and used in the army by sharpshooters.

Since their weapons were of varied types and constructions, the Militia Act made it the responsibility of the “brigade inspector to inspect [the brigade’s] arms, ammunition and accoutrements.” As Patrick J. Charles writes in another of his books, Armed in America: A History of Gun Rights from Colonial Militias to Concealed Carry (2018), “The militias of the thirteen colonies maintained different qualities of arms, including different bore lengths, firing capability, and ammunition. In 1779 Baron von Steuben began the process of correcting this deficiency.”

Thus Chapter 1 of Steuben’s Regulations begins with this very corrective to the problem of incompatible armaments: “The arms and accoutrements of the officers, non-commissioned officers, and soldiers should be uniform throughout.” By Steuben’s directive, the soldiers in a given unit could all draw on the same kind of munitions and could therefore pick up and fire each other’s weapons as needed in the heat of combat, or share a common stockpile of compatible musket-ball sizes and paper cartridges. Bringing order and regularity to the distribution and support of weapons made for a much more efficient chain of supply and a more consistently effective fighting force.

The Amendment granted a right to bear arms, but for a specific purpose — serving in a well-regulated militia — often ignored nowadays. For example, with the regulation on uniform armaments, we are so used to the idea of the army itself issuing consistent, materially integrated sets of combat gear — indeed the common term for a soldier, “G.I.,” means “general issue” — that the historical need to regulate a militia’s varied ordnance can be forgotten, and the legacy of Steuben overlooked. Yet the Second Amendment, in citing both a well-regulated militia and the right to bear arms, is closely bound up with his key work of Revolutionary regulations.

Who was Steuben, and how did he come to write his Regulations?

•

Baron von Steuben was born Friedrich Wilhelm Ludolf Gerhard Augustin von Steuben on September 17, 1730, in Magdeburg, Prussia, to a military family. In America he was known as Frederick William Augustus von (or de) Steuben.

Entering the officer corps of the Prussian army at the age of sixteen, Steuben served until the end of the Seven Years’ War (1756–63), rising to the rank of captain. For a time he was attached to the general staff of Frederick the Great. Leaving the army shortly after the Peace of Hubertusburg in 1763, Steuben at some unrecorded date during the next twelve years appears to have been created a baron (Freiherr), while acting as court chamberlain to the Prince of Hohenzollern-Hechingen. Yet he left Hohenzollern-Hechingen under obscure circumstances, and deeply in debt, in 1775 to seek posts with the British East India Company and the French and Prussian armies. All of these efforts came to nothing. At last, in the summer of 1777 he was brought to the attention of Benjamin Franklin, then in Paris as an agent of the embattled American colonies. By letter, Franklin presented him to George Washington as “a Lieutenant General in the King of Prussia’s service,” a vastly imposing, if fictitious, rank that greatly impressed both Washington and the Continental Congress — as did Steuben’s offer to accept only his expenses as payment until the Revolutionary cause succeeded. He was directed to report to General Washington at the Continental Army’s bleak winter encampment at Valley Forge in February 1778.

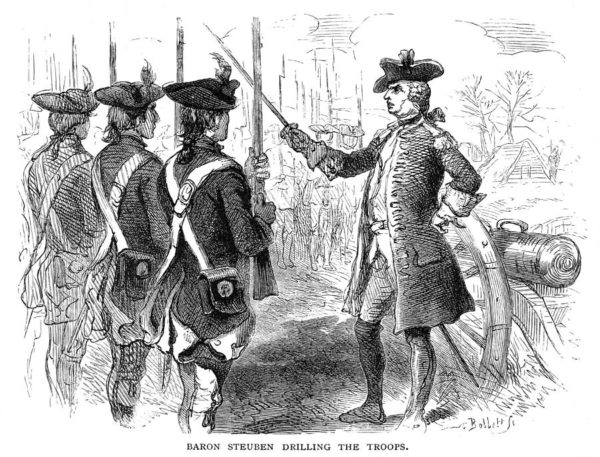

With his striking combination of qualities rare among the insurgents — his high professional military reputation, forceful Prussian bearing, and colorful personality — Steuben had a galvanizing effect on the downhearted, disorganized army and immediately became one of Washington’s most valued and trusted officers, winning appointment as inspector general and a mandate to train the army as an efficient fighting machine. All this despite the fact that Steuben spoke virtually no English and was obliged to work through interpreters.

At Valley Forge, Steuben formed a model drill company of one hundred specially selected men and undertook to drill them in person. As the drills progressed, he began to write (in brief installments, in French) the drill instructions that grew into the manual officially titled Regulations for the Order and Discipline of the Troops of the United States. This manual of drill and field-service regulations became the foundation of military training and procedure. Commonly known as the army’s “blue book,” and considered only slightly less authoritative than the Scriptures, it remained the official United States military guide until 1812.

Steuben’s transformation of his model company into a precision unit captured the imagination of the entire army. Rigorous drill suddenly caught on with the troops and led to what has been called “perhaps the most remarkable achievement in rapid military training in the history of the world.” By spring, Washington had acknowledged Steuben’s achievement by raising him to the rank of major general. From this turning point until the end of the war, the improvised Continental Army maintained a level of discipline comparable to that of the British regulars, with their centuries-old tradition.

•

There are, of course, far more glamorous books about warfare than Steuben’s. One only need think of Sun Tzu’s Art of War. Written sometime around 500 BCE and known in the West since the late eighteenth century, Art of War — with its keen insights into overarching strategy, battlefield tactics, and military psychology — has been admired by the likes of Napoleon, the German High Command, Mao Zedong, the leaders of Desert Storm … and Tony Soprano. Some of its most famous phrases, such as “All warfare is based on deception” and “Appear weak when you are strong, and strong when you are weak,” remain axiomatic, in part because intriguingly poetic. It is a grand “thought experiment” book for supreme commanders and heads of state. And sometimes for armchair generals.

Steuben’s book, in contrast, is essential for the common soldier on the ground. It is a tool for teaching rank-and-file troops everything from how to stand at attention, how to march, and how to fire a weapon to the precise meaning of each command spoken by their unit officers. As a drill manual, it depicts in exacting detail the specific actions called for by each verbal imperative.

It may seem like a relatively straightforward thing to aim and fire a musket. But Steuben knew that each step had to be carefully choreographed to make musket-bearers effective in the field. To give a sense of what the Regulations read like, here is the passage describing the first four orders and steps — out of more than two dozen — that recruits had to master for handling a weapon. (The underlined words are the officer’s spoken commands.)

I.

Poise — Firelock! Two motions.

1st. With your left hand turn the firelock briskly, bringing the lock to the front, at the same instant seize it with the right hand just below the lock, keeping the piece perpendicular.

2d. With a quick motion bring up the firelock from the shoulder directly before the face, and seize it with the left hand just above the lock, so that the little finger may rest upon the feather spring, and the thumb lie on the stock; the left hand must be of an equal height with the eyes.

II.

Cock — Firelock! Two motions.

1st. Turn the barrel opposite to your face, and place your thumb upon the cock, raising the elbow square at this motion.

2d. Cock the firelock by drawing down your elbow, immediately placing your thumb upon the breech-pin, and the fingers under the guard.

III.

Take Aim! One motion.

Step back about six inches with the right foot, bringing the left toe to the front; at the same time drop the muzzle, and bring up the butt-end of the firelock against your right shoulder; place the left hand forward on the swell of the stock, and the fore-finger of the right hand before the trigger; sinking the muzzle a little below a level, and with the right eye looking along the barrel.

IV.

Fire! One motion.

Pull the trigger briskly, and immediately after bring up the right foot, coming to the priming position, placing the heels even, with the right toe pointing to the right, the lock opposite the right breast, the muzzle directly to the front and as high as the hat, the left hand just forward of the feather-spring, holding the piece firm and steady; and at the same time seize the cock with the fore-finger and thumb of the right hand, the back of the hand turned up.

Clearly, there was a lot more than just the three-word “ready–aim–fire” in the disciplined discharge of a weapon. Other chapters expanded this well-controlled action into such tactical deployments as “Firing by Battalion,” “Firing by Divisions and Platoons,” “Firing Advancing,” and “Firing Retreating.”

Ranging comprehensively across military protocol, elsewhere the Regulations codify everything from setting up encampments to marching in formation, from daily inspections of the troops to the hierarchy of the official command structure. Under Steuben’s guidance, the Revolutionary forces were nothing if not “well regulated.”

•

In 1780, in recognition of Steuben’s success in turning the army into a disciplined fighting force, Washington granted Steuben’s wish for a command. He served as a division commander in the final siege of Yorktown, where his intimate experience with siege tactics in the Seven Years’ War contributed substantially to the final defeat of the British. Washington’s last official act as wartime commander was to write a letter to Steuben commending his service.

After the coming of peace, Steuben became an American citizen, retired from the army, and made his home in New York. In 1786 the state of New York granted him 16,000 acres north of what is now Utica. As in his youth, however, Steuben was improvident about personal finances; a group of influential friends, Alexander Hamilton among them, had to rescue him from bankruptcy in 1790, the same year that the federal government finally decided to repay his wartime service with a pension of $2,500. He died on November 28, 1794.

Baron von Steuben brought unique qualities to the Revolutionary cause: his depth of military training and minutely detailed grasp of the techniques of command were precisely what the bedraggled Continental Army desperately needed. He was among the few truly indispensable figures in the achievement of independence. His likeness can be seen in John Trumbull’s mural The Surrender of Lord Cornwallis at Yorktown in the rotunda of the Capitol, in Washington, D.C.

(Seven paragraphs of this essay originally appeared as my unsigned Publisher’s Note in Baron von Steuben’s Revolutionary War Drill Manual [New York: Dover Publications, 1985], reprinted by permission. The rest was written in September 2018.)

Fascinating history!

The fact that ‘A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed’ is a single statement seems to require us to recognize the writers’ intent to establish a dependency: the phrases or conditions which follow “A well regulated Militia” are dependent upon, are pertinent “only” in, this situation to which the latter phrases refer (back). To modernize the language, we could state: “Because a well regulated Militia is necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms shall not be infringed upon.” [I am not wholly comfortable with the existent comma after the word “Arms”]

It seems clear that those who want to isolate the dependent phrase, “the right of the people to keep and bear Arms…shall not be infringed” ignore the sentence’s construct.

With an aversion to cold, dry facts-I thought you made it

especially interesting and colorful by weaving Steuben’s

personality throughout.

Very enjoyable and the visuals added a lot.

The US Supreme Court, while repeatedly overturning gun control legislation, has referenced this syntactic dependency and indicated that properly framed gun control laws would not be overturned. We need to get that done!

As Leggio points out, it is bizarre that “Originalist” Supreme Court justices, who claim fealty to the original intent of the Founders, choose to ignore richly documented history and overlook the “well regulated Militia” phrase when interpreting the Second Amendment. Is it possible that political dogma trumps historical facts in this case ? Could our “Originalist” justices really be that hypocritical and cynical? Let’s think what portends for our republic . . . .