With contributions by Faya Causey, Sara Green, Annemarie Iker, Ariel Kline, and Anna Swinbourne. Exhibition catalogue. Princeton University Art Museum, 2020. Distributed by Yale University Press, New Haven and London. 192 pages. 143 illustrations. $45.00

Reviewed by James Leggio

The exhibition Cézanne: The Rock and Quarry Paintings presented a group of paintings — “small in number, large in importance,” as curator John Elderfield writes — along with related watercolors and documentary materials. It was the first major exhibition devoted to the artist’s profound interest in rock formations and, more generally, in the then-burgeoning science of geology, which helped shape his conception of landscape.

Considered in the short term, the exhibition, unfortunately, fell into the pandemic abyss. After opening at the Princeton University Art Museum on March 7, 2020, the show was forced to close within a week by Covid-19 restrictions, and plans were cancelled for its second venue, the Royal Academy of Arts, in London.

But considered in the long term, the project, preserved in book form, remains of enduring interest, in part by its drawing attention to the truly long term — the eons of deep, geological time rendered visible in the stratified rocks and excavations that Cézanne painted. We have much to learn from this relatively small but focused body of works, retracing time’s slow, ineluctable passage and unearthing the deep past of his subject’s stony matter.

Catalogue contributor Faya Causey conveys the vastness of geological time evident in these works by quoting Charles Darwin’s advice, in the Origin of Species (translated into French in 1862), that one has to “examine for himself great piles of superimposed strata and to watch the sea at work grinding down old rocks and making fresh sediment before [comprehending] anything of the lapse of time, the monuments of which we see around us.”

The Princeton book gathers together Cézanne’s geological pursuits from four sites. One site lies in the north: the Forest of Fontainebleau, forty miles from Paris, is known as much for its unusually shaped sandstone boulders as for its oaks and pines. The others cluster in the south, including the rocky coast along the Bay of L’Estaque, and two locales near the artist’s native town of Aix-en-Provence: the stony, wooded grounds of the Château Noir, and the ancient, abandoned Bibémus Quarry — over which towers serenely in the distance the biggest rock of all, the massif Montagne Sainte-Victoire.

Readers can explore each site in detail, since each has its own section within the plates. Each section is also equipped with its own Introduction, excellently written by Anna Swinbourne, and catalogue entries provided by Annemarie Iker, Ariel Kline, and Sara Green. All of them benefit from Faya Causey’s detailed overview of the state of geological knowledge in Cézanne’s time, mentioned above, along with Causey’s new research, included in the book, into important related documentary drawings.

“The Geological Skeleton”

The catalogue takes as its epigraph Cézanne’s remark to Joachim Gasquet, around 1897:

In order to paint a landscape well, I first need to discover its geological foundations.

The nature of this “need” may not be immediately obvious. Apparently, the Impressionists Cézanne had exhibited with in the 1870s felt no such need. The way that Monet, for example, evoked the shimmering effect of light in Parc Monceau, or gave a dazzling surface to the fields near Argenteuil, possess a beauty that seems, quite intentionally, skin-deep.

But as John Rewald once wrote in a catalogue entry on the Château Noir painting shown below:

Because of the strange way in which Cézanne humbly submitted to his perceptions while dominating them, he remained attached to nature’s permanence rather than allowing himself to be distracted by the charm of evanescent conditions of light. His concerns lay in the complete integration of his observations on the picture plane.

In the twenty-five rock and quarry paintings catalogued here, from across decades of his career, Cézanne sought to “discover” nature’s material permanence, its underlying “geological foundations.”

How, precisely, did the artist go about the elusive process of discovery? That long and complex story is told in Elderfield’s intricately argued catalogue essay. Let me very crudely approximate one of its points, as I understand it.

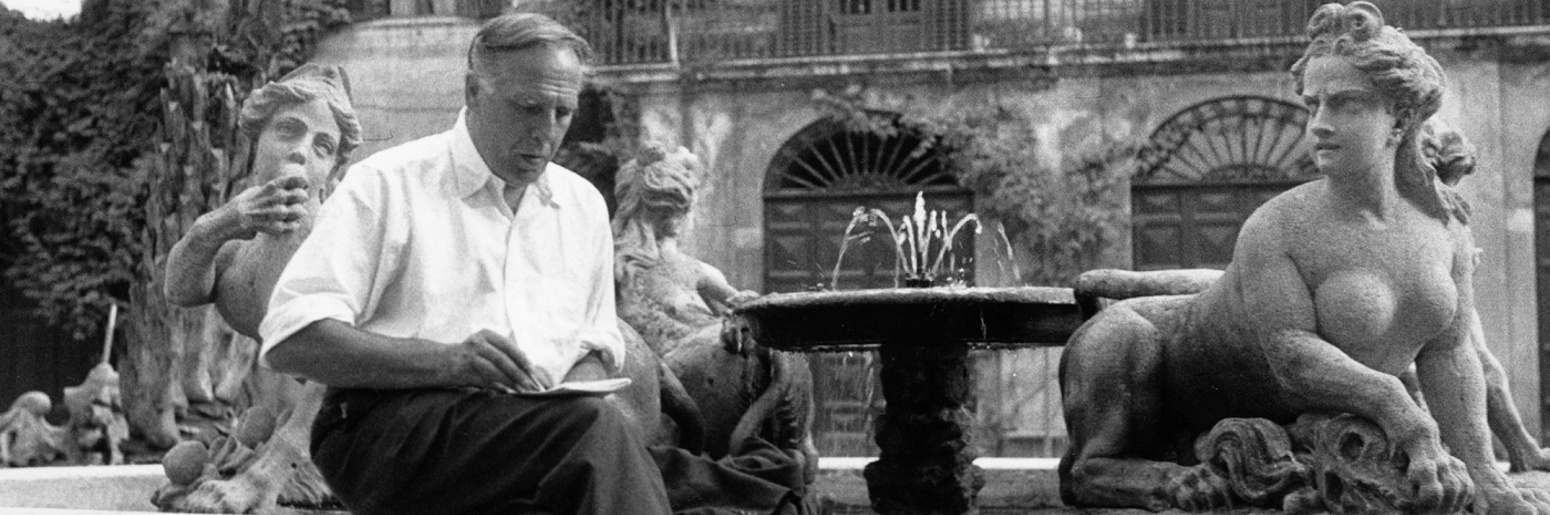

A serendipitous juxtaposition of geological and artistic methods, observable on a sketchbook page (shown below, and reproduced in the catalogue), offers a kind of shorthand guide. One image on it is a portrait of the artist’s friend Antoine-Fortuné Marion, who was to become a distinguished naturalist; he was called “géologue et peintre” for a combination of interests matching Cézanne’s own, and the artist learned much about the current state of geological study from him. The other image, sharing the page with Marion, is a sketch of a studio écorché, a flayed figure that, with its skin removed, revealed to student artists the flexing muscles underneath, supported in their pose by the skeleton, as an anatomical foundation for drawing, painting, or sculpting the living figure in all its vibrant corporeality.

What Cézanne found in geology — revealing the earth’s hidden, form-giving strata beneath the surface — was, perhaps, a landscape equivalent of the écorché. It helped articulate the unique underlying masses and volumes.

Some such notion is likely behind this account of the artist at work on “the landscape as an emerging organism,” attributed to Madame Cézanne by Maurice Merleau-Ponty in “Cézanne’s Doubt” (1945), quoted at length in the Princeton catalogue:

He would start by discovering the geological foundations of the landscape; then, according to Mme Cézanne, he would halt and look at everything with widened eyes, “germinating” (germinait) with the countryside. The task before him was, first, to forget all that he had ever learned from science and, second, through these sciences to recapture the structure of the landscape as an emerging organism. . . . Then he began to paint all parts of the painting at the same time, using patches of color to surround his original charcoal sketch of the geological skeleton. The picture took on fullness and density; it grew in structure and balance; it came to maturity all at once. “The landscape thinks itself in me,” he would say, “and I am its consciousness.”

Thus, a landscape painting is bodied forth, as Cézanne puts the muscular flesh of its full, dense volumes onto “the geological skeleton” of his charcoal sketch.

Rock of Ages

Of the four groups of site paintings, those depicting the Bibémus Quarry may be to some the most intriguing.

Substrate rock formations can be released to view from the skin of topsoil in different ways: some are pushed up to the surface by the earth’s internal forces; others have been exposed by natural erosion. Still others, though, as at Bibémus, were laid bare through excavations carried out by human toil. They thus bring into a formerly pristine spot the evidence of historical intrusions, in this case an archeological site dating back to the Roman Empire and abandoned as a working quarry in 1885. It’s not surprising that the main catalogue essay is titled “Excavations,” a leading theme throughout.

Contributor Anna Swinbourne puts before us this quarry of richly colored stone as Cézanne experienced it. She describes the advantages it offered him, both personal and visual:

Within its confines, he could paint sheltered from the mistral when it blew, protected from the sun when it blazed, and, most importantly, in uninterrupted solitude. Only the sounds of wildlife or a chorus of cicadas in the warmest season would pierce its pervasive quiet. The quarry’s spaces varied greatly — ranging from cloistered and intimate to open and colossal — and were defined by marred and glowing faces of cut limestone.

With a canvas like this one from Essen (above), Elderfield speaks of “the equivalence of paint and stony substance.” Especially on the right side, the close-up planes of ochre stone become identical with the textured surface of oil paint built up on the picture plane, stroke by stroke.

In addition to their pressure of spatial extent, the quarry paintings also have a temporal extent, and as such form the climax of that section of the curator’s essay headed “Time Travel,” a passage rich in paradox. He sees two different temporal scales at work on this site:

One shows time moving from the past at the top of the quarry to the present at the bottom. . . . The second temporal scale runs in the opposite direction, from Roman times at the top to earlier and still earlier ages as it descends.

What’s explained here is basic to the process of excavating strata. Seen one way, the layer back up where you started, at the surface, is the past, while the level to which you have currently dug down becomes the present, where you are now active. But seen the other way, because of its ancient past, the state in which the Romans left the place became the “present” site as known in later times, while further excavation over the course of the quarry’s subsequent working life took you down to deeper, earlier ages, long before the Romans.

Or, as Elderfield writes:

. . . each wall of Bibémus is a time-travel diagram in depth down to where Cézanne had set up his easel — in a distant past before the human drama had begun.

Excavating the Modern

The essay title “Excavations” has further ramifications. The process of excavation encompasses not only the quarrying of stone as at Bibémus, but also the idea of an archeologist’s dig.

Excavations of a more recent period come into play as well through the Rock and Quarry Paintings exhibition. In an article for the Princeton University Art Museum’s members magazine titled “Alfred Barr’s Insomnia — and the Awakening of Cézanne’s Interest in Geology,” Elderfield assembles what amounts to an art history detective’s report, unearthing the minutiae of Barr’s activities in the 1930s that brought to light the best documentary evidence we have about Cézanne’s interest in geology. The final point is this:

The most critical source of information about the Cézanne-Marion relationship, however, is the eyewitness account offered by Marion’s letters to their common friend, the musician Heinrich Morstatt. These letters remained unknown until they were published, also in 1937, by Alfred H. Barr, Jr., the Princeton University graduate who had given up his post-graduate work at Harvard in August 1929 to become, at age twenty-seven, the first director of The Museum of Modern Art.

The theme of excavating the past of art history (and of art museums, the Modern in particular) arises in part because some passages of the exhibition’s argument seem to unearth another now-historical site — the Modern’s Cézanne: The Late Work (1977) — the source of the brief citation of John Rewald above and, as it happens, the first Cézanne exhibition I ever saw. (Indeed, I learned in reading David Anfam’s comprehensive review of the Princeton project that it has induced like-minded individuals to “flash back to MoMA’s Cézanne: The Late Work.”)

Aside from Rewald’s, let’s consider two other contributions from the nine essays in the imposing catalogue for The Late Work. The two took almost diametrically opposed approaches. The depth of divergence between them might be said to inform the line of argument in the Rock and Quarry Paintings show.

One was “The Logic of Organized Sensations,” by the artist and curator Lawrence Gowing, whose choice of title, quoting Cézanne, tips you off that he takes a quasi-phenomenological approach. In his Acknowledgments to the Princeton book, Elderfield’s last sentence honors two revered figures in the history of art history: “Finally, I am again pleased to acknowledge the influence on my understanding of Cézanne of John Rewald and Lawrence Gowing, who introduced me to the study of his art some forty-five years ago, and whose foundational work on it resonates to this day.” Gowing’s 1977 essay, cited in the Princeton book, comports well with Elderfield’s conclusion that in depicting these scenes, “Cézanne indubitably had a bodily as well as visual experience.”

A passage from “The Logic of Organized Sensations,” analyzing a watercolor also in the Princeton catalogue, confirms as much (though in terms more literal than Elderfield’s):

How much sensuality there still was in the balance of his art is seen . . . in a watercolor [shown below] at The Museum of Modern Art painted at the Château Noir a little further along the rocky bluff that had provided his majestic upright motifs before. The rounded lumps in which the limestone is weathered cluster over a slanting cleft; it is the kind of place where one may feel that the genius loci has disturbingly developed a real physique, and Cézanne has painted it like a body.

The other essay from the 1977 MoMA catalogue, placed at the end of that book, perhaps as the intended climax and underlying raison d’être, was William Rubin’s “Cézannisme and the Beginnings of Cubism,” which pressed on, in its sense of linear progress, to Picasso and Braque. Rubin’s editorship of the Cézanne: The Late Work catalogue is also cited in The Rock and Quarry Paintings, but not his “Cézannisme” essay. Nonetheless, that essay seems to be encompassed by a comment Elderfield made in a talk at the Princeton show’s opening (video available on the exhibition’s website; text subsequently printed in The Brooklyn Rail):

. . . while both Picasso and Matisse said that Cézanne was the father of us all, like all artistic fathers, he is not responsible for what his children do. In fact, what the children did was, of course, very different from what Cézanne did. Certainly, the common understanding that Cézanne’s principal impact was on the development of Cubism is hardly supportable. Working on this exhibition, I have felt even more that associating Cézanne with the increasingly reductive geometric painting of the early part of the twentieth century is a wrong understanding of his importance. His increasingly proximate views of rocks seem to take you to the epicenter of his art in so vividly binding their depicted surfaces to the literal surfaces of his paintings. That constituted the great Cézannean revolution. Not that Cézanne made Cubism possible.

One might well think that the pendulum has swung back toward the possibilities offered by a phenomenological view, perhaps picking up some elements of Gowing’s account. Carol Armstrong’s remarkable recent book, Cézanne’s Gravity (Yale, 2018), which devotes extended attention to Merleau-Ponty on Cézanne, cites “The Logic of Organized Sensations” (as well as Theodore Reff’s essay in the 1977 catalogue) on the “constructive brushstroke,” the basic component of Gowing’s logic.

Precursors

Another factor that makes Gowing notable in the Modern’s passage through time was his association, in the MoMA orbit, with notions of a precursor to modernist art.

In 1966, Gowing wrote the catalogue for the Modern’s exhibition Turner: Imagination and Reality. It wasn’t every day that The Museum of Modern Art, which long defined “modern” as beginning with Cézanne, mounted an exhibition of a Romantic artist who died in 1851. In his Foreword to the catalogue, the Modern’s director of exhibitions and publications, Monroe Wheeler, gave this reason for the seemingly anomalous endeavor: “Transcending the concepts of romantic art, he reached out into the borderland between representation and the abstract.” With that dubious assertion — Turner “transcending” his own time to become an ambassador to ours — built into its rationale, the show, though a great success with the public, did not always please the critics.

Twenty-five years later, the Turner exhibition had an unexpected coda at the Modern. For in 1991, revisiting the show’s mixed reception, Elderfield published an article, “The Precursor,” in the MoMA annual series Studies in Modern Art. It addressed the intellectual and critical puzzles the show posed, within the context of abstract painting as understood in the mid-1960s.

At one point, down in the weeds of trying to identify precisely which artists Turner supposedly precursed, Elderfield quotes Hilton Kramer’s assertion in a review of the 1966 exhibition — “Turner comes to us at the present moment as an inspired precursor of the attempt to create a pictorial style out of the materials of color alone” — and evaluates it thus:

This seemed far more plausible. The Museum of Modern Art was showing Turner because he was a Color Field painter. But which one? Frankenthaler? Olitski?

Other names follow: Kenneth Noland, Morris Louis, even Mark Rothko; just within this one area of painterly practice, we are awash in candidates to be Turner’s heir. And more widely, as the accounts in the press at that time of just which artist(s) Turner foreshadowed kept proliferating, Dore Ashton shifted the debate topic altogether by focusing not on alternative contemporary heirs but rather on an alternative precursor — Monet — writing: “The resurrection of fathers is a frequent occurrence here, though their moments of worship are brief . . . [they] satisfy a peculiar American craving for history.”

Elderfield draws this conclusion from the competing searches for parenthood:

So each generation creates its own paternity for itself — or as a contemporary of Turner’s put it rather more eloquently, the child is father of the man.

The point here, I think, is not whether a tolerable argument could be cobbled together for Turner (or Monet) as an imaginable precursor to one wing or another of contemporary abstract painting. Rather, the point is that the very idea of a precursor is so subjective, and so riddled with inner contradictions, that it’s a misleading basis for historical analysis. By so effectively problematizing precursorhood, the author of “The Precursor” quietly offers a healthy corrective to those teleologically preordained successions of the-prophet-foreshadows-the-savior variety, based on biblical typology.

And it might occur to an outside observer that perhaps the artist to benefit the most from overturning the precursor paradigm would be Cézanne, whom some within the Modern milieu had reduced to a prophet of Cubism — a sort of John the Baptist to Picasso’s Messiah.

Yet “The Precursor” article does make an illuminating distinction between misguided teleology and creative aspiration, thereby casting a retrospective light on Cézanne: The Late Work:

. . . it used to be said that Monet had outlived himself, but in fact he went further than his contemporaries. . . . Here lies the attraction within modernism (and significantly, I think, within later modernism), to precursors who have identifiable late styles which do not seem as much endings as beginnings. Thus, late Monet, late Turner, late Cézanne, late Matisse, all may be perceived as paradigmatic of the wish to go beyond the established modernist past and thereby to open up a new modernist future.

•

In view of Elderfield’s homage to John Rewald and Lawrence Gowing, and in this instance his continued attention to the ramifications of Turner: Imagination and Reality, I want to give Gowing the last word. There remain rich veins of his writings to be explored afresh.

For example, in another twist to a once-dominant MoMA orthodoxy, Gowing returned to write the catalogue essay for Paul Cézanne: The Basel Sketchbooks (MoMA, 1988). His is a working-artist’s evocation of how Cézanne manipulated material solidity with a pen or pencil, thereby deftly redrawing the lines of influence surrounding this sheet of bather studies:

It is only lately that opinion has rallied around Cézanne’s enduring achievement — of rebuilding the creditable solidity of an image . . . Those who lamented Cézanne’s bathers, which were held to be “not what he was good at,” put their finger on exactly what qualified Cézanne to take the crucially courageous, foolhardy option which retrieved painting from its falsification in the Salons. The bather who holds the mirror for her morosely dubious sisters releases them from the faked fidelity of their time. Below the group of four and the tentative likeness of himself in the cap with the shiny peak there are two versions of the bather with her head enfolded in her arms, one with a poetic tenderness, the other hard-bitten and prosaic. She was the earliest and latest of the party, descended from Delacroix’s Le Lever, still rapturous and self-embracing in the Barnes Foundation Large Bathers in readiness for her liberation as a demoiselle in the rue d’Avignon and the poetic freedom of another time.

(December 2020)