With contributions by Leontine Coelewij, Grace Deveney, Rachel Jans, Susanne Neuburger, Andrea Nitsche-Krupp, Valentina Ravaglia, and David Toop; with excerpts from Paik’s writings. Exhibition catalogue. Tate Publishing, London. DelMonico Books / Prestel, New York, 2019. 150 illustrations. 176 pages. $50.00. Exhibition venues: Tate Modern, London: October 17, 2019-February 9, 2020. Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam: March 14-October 4, 2020. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art: May-October 2021. National Gallery, Singapore: Opening November 2021.

Reviewed by James Leggio

This new assessment of Nam June Paik (1932-2006), widely known as “the father of video art,” accompanies a traveling retrospective organized by Tate Modern and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Comprehensive in scope and rich in detail, it gives him his due as among the leading experimental artists of the latter half of the twentieth century.

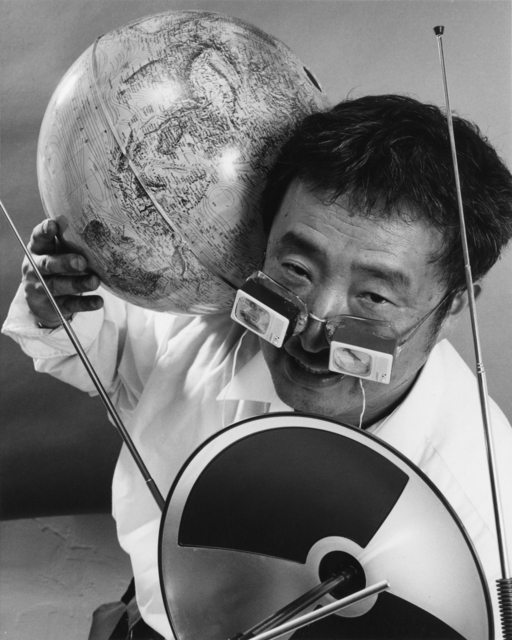

One of the first images in the book playfully shows Paik as an almost godlike figure. Having long been considered a global visionary, here he supports the weight of the world on his shoulder, like a modern Atlas, while peering over his signature TV Glasses, his form framed by antennae.

Lightheartedly, Paik undermines his heroic status through a self-deprecating pun, paying sly homage to fellow video artist Charles Atlas, who had collaborated with him on Merce by Merce by Paik in 1975-76 — and was often confused with the famous bodybuilder of the same name, whose muscular physique could still be seen in print advertising in the 1970s.

The globe-bearing Paik appears in a presentation of Good Morning, Mr. Orwell at the Kitchen, New York, on December 8, 1983, which looked ahead to the hour-long broadcast with the same title on January 1, 1984. That New Year’s Day marked the dawn of the year George Orwell’s novel Nineteen Eighty-Four, with its all-seeing eye of Big Brother, had been teaching us to dread since its publication in 1949.

Those in the communications industry were perhaps the most anxious about future uses and abuses of television. In 1958, in a milestone speech in the immediate aftermath of the McCarthy Era, broadcaster Edward R. Morrow tried to strike a balance between TV’s entertainment value and its key role in maintaining a healthy national discourse:

This instrument can teach, it can illuminate; yes, and even it can inspire. But it can do so only to the extent that humans are determined to use it to those ends. Otherwise, it’s nothing but wires and lights in a box.

Paik believed deeply in the power of “this instrument” to teach and inspire. He saw the potential of technology — “wires and lights in a box” — to become a positive force in human affairs. Promoting the term electronic superhighway, he believed that connectedness could make possible a kind of global utopia made out of what was (in every sense) “free” information. And so, he devised an international satellite-TV performance event that offered a joyous antidote to Orwell, allowing us to welcome the long-anticipated year 1984 with a friendly “good morning.”

As contributor Valentina Ravaglia writes about the broadcast event, in the exhibition catalogue under review:

A hectic video montage simulating the experience of “channel surfing,” Good Morning, Mr. Orwell included live events from WNET-TV’s studio in New York and the Centre Pompidou in Paris; it was also broadcast in Korea, the Netherlands and West Germany. This was an optimistic retort to George Orwell’s vision of a dystopian future, now supposedly present, in which telecommunications are deployed as instruments of mass surveillance and oppression. Paik visually brought together events happening simultaneously in the USA and Europe, overlapping in the same frame through split-screen and chroma-key effects; John Cage could thus be seen playing music in New York over a performance by Joseph Beuys shot in Paris. The juxtaposition of high art and entertainment lured viewers with pop music and sketch comedy while exposing them to avant-garde figures such as Charlotte Moorman and Allen Ginsberg; pop band Oingo Boingo alternated with images of Merce Cunningham dancing over footage of Salvador Dalí. A music video for a Peter Gabriel and Laurie Anderson duet also featured prominently, as well as computer animations accompanying a Philip Glass composition. Paik even reclaimed the inevitable technical difficulties, like signal failures, as productive random variables.

(Watch the full broadcast.)

It was a red-letter day in the history of the Global Village. And Paik’s heady vision of a linked-up video world had made it happen.

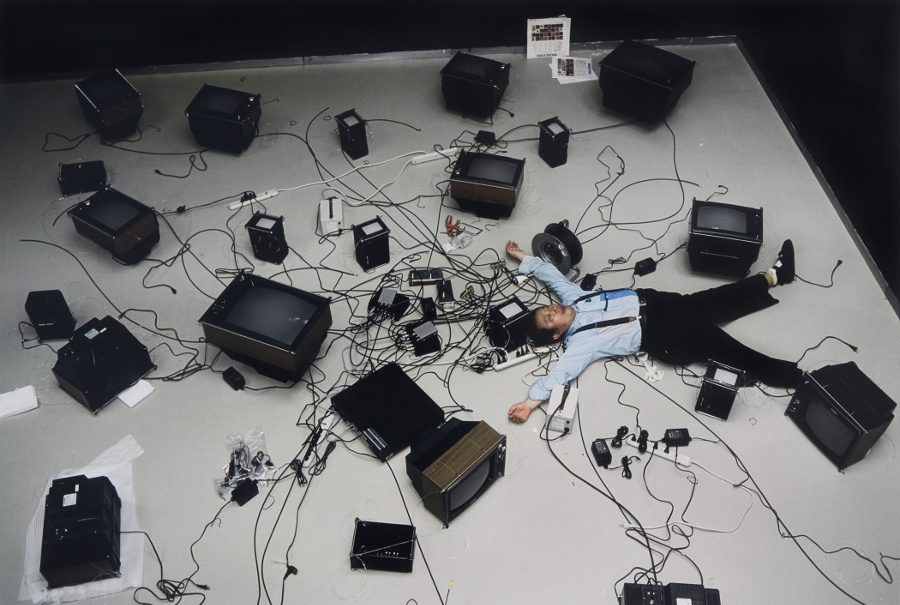

The popular theorist Marshall McLuhan had said that media devices were “the extensions of man.” In the photograph (below) of Paik lying with his arms and legs splayed out among TV monitors, entwined with elaborate wiring that seems like an extension of his own nervous system, he turns into the very embodiment of video connectedness — a Vitruvian Man for the media age.

Fame in Flux

Since his death in 2006, Paik’s grand “open circuits” optimism, though quite firmly grounded in his mastery of emerging technologies, has unfortunately not aged well in some respects. We now take for granted many modes of audiovisual interaction he helped pioneer, giving little thought to how they came to be. And in an age of rogue cable outlets, internet trolls, and reckless tweet-wars, we’re less trusting of utopian media schemes.

Moreover, with the loss over the years of many of his friends and collaborators, among them Cage, Cunningham, Moorman, and Beuys, there’s been a seismic generational shift. Now that Paik has moved irrevocably into the realm of the historical, it requires an effort of sympathetic imagination for audiences to rediscover what was of continuing value in his unusual brand of hands-on radicalism.

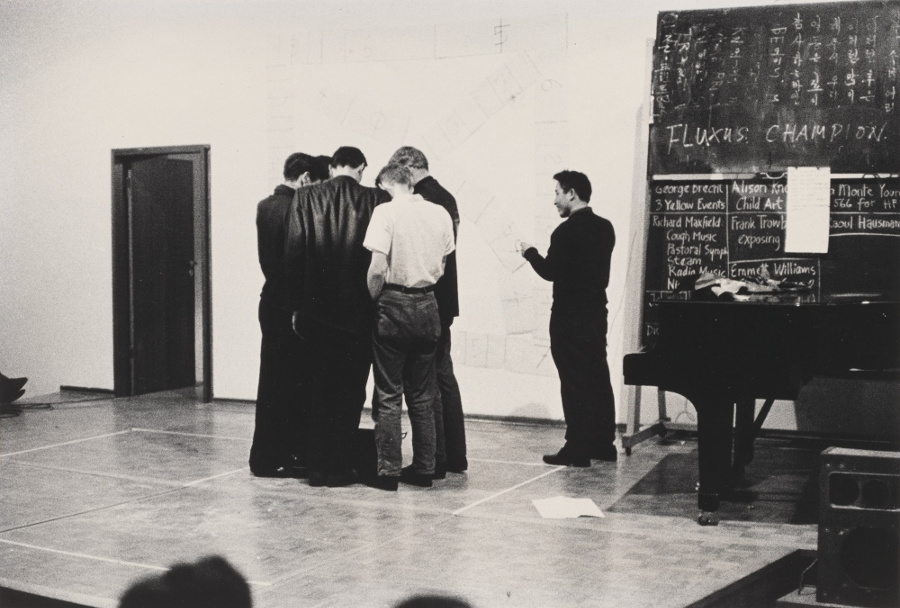

We can sense this state of affairs in reservations expressed by some of the reviewers when the present exhibition opened at Tate Modern in London — especially concerning Paik’s early affiliation with the interdisciplinary Fluxus group, famous for its épater le bourgeois performances. After participating in its activities at a formative stage of his work, as Beth Williamson noted in Studio International, “Paik continued to take inspiration from Fluxus and bring artists, composers and performers together throughout his career.” Some other reviewers, however, saw his Fluxus heritage as dated or quaint. Bidisha wrote in The Guardian:

In the Fluxus group, as with all Paik’s collaborators, it’s starkly noticeable that there are almost no women. One 1963 piece, Paik’s Fluxus Champion Contest, is literally a willy contest: men piss into a bucket while singing the national anthem, and whoever’s still singing and peeing at the end wins. It’s depressing. These gifted guys want to dissolve every rule, except that of patriarchy, of the men’s club. There is a large room dedicated to footage of Paik’s collaborative performances with his friend, the cellist Charlotte Moorman — which resulted in her becoming notorious as the “topless cellist.” Paik’s work crystallises very obviously once he leaves Fluxus behind.

A widening of Fluxus studies beyond the men’s-club model has been under way for quite a while. For example, in 2009, Women and Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory devoted a special issue to “Women and Fluxus: Toward a Feminist Archive of Fluxus,” guest edited by Midori Yoshimoto. Another resource, “Experimental Women in Flux” from 2010, on the Museum of Modern Art’s website, brings in MoMA’s extensive library of documentary material.

Our understanding of women in Fluxus is indeed changing. A review of the major show devoted to Moorman at New York University’s Grey Art Gallery in 2016 appeared under the long-overdue headline “Charlotte Moorman Is Finally Remembered as More Than ‘The Topless Cellist.’”

The catalogue under review also makes it clear that the frankly bodily aspect of Paik’s early work, as in the Champion Contest, was not quite an all-male enterprise. Contributor Andrea Nitsche-Krupp devotes an essay to Paik’s Serenade for Alison (1962), written for founding Fluxus member Alison Knowles. The piece could be considered a counterattack on the critical reception of the “Flux Fest” that year in Wiesbaden, the first official presentation of the newly minted Fluxus group. Among other things, the score indicates:

Take off a pair of nylon panties, and stuff them in the mouth of a music critic.

Take off a pair of black-lace panties, and stuff them in the mouth of the second music critic.

Take off a pair of blood-stained panties, and stuff them in the mouth of the worst music critic.

The present era, which highly values body art, often as a subset of performance art, could witness a reappraisal of Paik’s youthful transgressions against personal decorum. Nonetheless, the Fluxus group’s festive, anarchic disdain for authority can still lead to dismissal of his involvement with it as a sophomoric episode that happened to precede his emergence as a major artist.

Admittedly, in Paik’s Champion Contest, as in other of his more outlandish early pieces, there is indeed an in-your-face juvenile element, often fixed on shy-making genital display, such as the infamous Young Penis Symphony (1962), in which a lineup of male participants stood behind a curtain that had holes cut out of it at groin level; or the transistor-miniaturized TV Penis (1972), worn in performance by Stuart Craig Wood.

It’s also true, of course, that Champion Contest is not the most glorious example of the many ways Paik anticipated the future. But inspired silliness of this kind is still part of our culture, and continues to inform in novel ways. For instance, one of the 2015 Ig Nobel Prizes — awarded to unlikely achievements in the sciences, in a ceremony hosted at Harvard — went to the group of physicists who established a “Universal Law of Urination,” which calculated a normative trans-species timeframe of 21 seconds (give or take 13 seconds) to empty the bladder, whether for a house cat or an elephant. In Paik’s Champion Contest, Frank Trowbridge of the United States won with a time of 59.7 seconds, a notable accomplishment in light of subsequent research.

•

Thomas McMullan in Frieze expressed concern about a different aspect of the London show, its emphasis on documents:

The exhibition makes much of placing Paik in a social context. This can sometimes see the artist becoming lost in the mix of his famous friends — like John Cage and Joseph Beuys — or bogged down in endless Fluxus documentation.

To be sure, that’s a worry in exhibiting Fluxus and other early work, which now exists largely on paper. Jonathan Jones, too, in The Guardian, found the exhibition’s sheer volume of printed documentation problematic, even stultifying, and wrote of the installation scheme at Tate Modern:

The power of Paik’s art lies in its lightheartedness. . . . Paik’s gleeful beauty gets buried in this doomed attempt to turn him into a mighty modern artist on the scale of, say, Robert Rauschenberg. After that teasing glimpse of his magical way with video, you have to drag yourself through room after room, each revisiting his early career as a member of the international 1960s group Fluxus in impenetrable detail. To read every single poster, flyer and magazine — all assiduously assembled in vitrines and dwelling on long-forgotten happenings in Darmstadt — would take a lifetime. And I’ve got TV to watch. It’s not that Fluxus was boring. It’s just that you clearly had to be there.

Navigating a large exhibition, spread out through a sequence of gallery spaces, we fragile humans, with our tired feet and aching backs, may have little patience for the dusty documents of long-ago moments, now trapped in vitrines for our inspection. Understandably, we want to proceed quickly to the spectacular video works the artist is known for: sculptural pieces, installations, single- and multi-channel videos, recordings of live broadcasts, and so on. We eagerly want to see TV Garden bloom again, or TV Buddha once more contemplate its own image, and now have them joined — for its first showing since its 1993 debut — by Paik’s ambitious Sistine Chapel.

Given the choice between these landmark video works, on the one hand, and on the other, showcases filled with fading ephemera, the museumgoer’s priorities are clear.

The printed book, however, made to be read at home in a comfy chair, is a much more forgiving medium than the marathon exhibition. A catalogue as fine as this one invites us to peruse at leisure the historical photographs, deadpan documents, and lively anecdotal evidence left in the wake of Paik’s cyclonic early career.

Still, though, as Jones said about Fluxus, “you clearly had to be there.” Fortunately, in a way we can be. Documentary footage of some performance pieces appears within the exhibition. And for the reader at home, audiovisual representations of some Fluxus-related actions and musical pieces are available online; live links to them are included in the discussion below. These momentary flashbacks do at least give us some fleeting sense of being there, experiencing the multimedia works as the living performances they were.

In addition, those audiovisual recordings show how the early pieces, often now undervalued, opened a gateway to the great video creations for which Paik is celebrated.

Paik the Musician

Looking at the early work reminds us that Paik trained as a musician. In his youth in Korea, he studied classical piano. After his family resettled in Japan during the Korean War, he attended the University of Tokyo and wrote his thesis on Arnold Schoenberg, graduating in 1956. He then relocated to Germany, studied with Wolfgang Fortner at the Conservatory of Music at Freiburg, met John Cage in Darmstadt, and encountered Karlheinz Stockhausen at the Studio for Electronic Music in Cologne.

He was drawn as well to the maestro of Fluxus, George Maciunas, who succinctly defined the group’s aesthetic by giving its 1962 Düsseldorf show the apt title “Neo-Dada in der Musik.” (It included Paik’s Sonata quasi una fantasia, a neo-dada exercise in which he stripped while playing Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata.)

In order to fully understand Paik’s development as an artist, we need to understand the role music played in leading him, ultimately, toward video.

To follow the steps in Paik’s career as a musician, Michael Nyman’s essay “Nam June Paik, Composer” (in the catalogue of the Whitney Museum’s 1982 Paik retrospective, curated by John G. Hanhardt) remains essential. Nyman lays out the course of Paik’s compositional career. After working very early on with folk-inspired material and then in relatively conventional serial and non-serial modes, Paik made a radical break in 1959, inaugurated by his Hommage à John Cage. The next great milepost was 1964, the year he moved to New York, which marked the beginning of his collaboration with Charlotte Moorman.

(Watch a 45-minute concert re-creating some of Paik’s compositions.)

Let’s pursue these two turning points in Paik’s musical career — his association with Cage and then with Moorman.

The Piano After John Cage

It’s revealing that Edward R. Morrow had referred to the TV set as an “instrument.” Before Paik fell in love with it, he passionately loved other instruments — musical instruments. Before he brought the TV to life, not only as a vehicle for communication but as a physical object, he brought musical instruments to life.

In giving instruments a sense of lively animation, the early performance pieces for piano show Cage’s influence, if in a somewhat unexpected way.

The usual way is demonstrated by this capsule comment in the general “Artists” section of the Tate website:

Cage is perhaps best known for his 1952 composition 4′33″, which is performed in the absence of deliberate sound; musicians who present the work do nothing aside from being present for the duration specified by the title. The content of the composition is not “four minutes and 33 seconds of silence,” as is often assumed, but rather the sounds of the environment heard by the audience during performance. The work’s challenge to assumed definitions about musicianship and musical experience made it a popular and controversial topic both in musicology and the broader aesthetics of art and performance.

This is certainly the standard take on the piece. But what may be left out of this account is the sheer material reality of musical instruments, their bodily presence, an omission that interdisciplinary critics have been trying to address for some time.

Most notably, in his book Panaesthetics: On the Unity and Diversity of the Arts (Yale, 2014), Daniel Albright offered a striking observation about 4′33″. Albright said that though no instrumental sound is heard, it actually mattered which kind of musical instrument was “performing”:

. . . Cage’s 4′33″ performed by an oboist differs strongly from 4′33″ performed by a pianist; the look of an oboist holding his instrument in his lap, relaxed yet secure, is not the look of a pianist hunched before her instrument, refusing to play.

In romance fiction, unrequited lovers supposedly say, “We could have made such beautiful music together.” Concert musicians, bound in an intense, lifelong partnership with their chosen instrument, are not as wistful. Many of these performer/instrument spousal pairings do indeed turn out to be happy marriages, but others develop into a love/hate relationship. And thus, Albright’s example implies two very different scenarios with the significant other, the instrument. The oboist almost appears to be abetting his delicate, lightweight, woodwind partner’s rebellious silence, letting it rest comfortably in his care.

The pianist, though, confronts a formidable, heavyweight rival that was, we should bear in mind, largely a product of the Industrial Revolution, constructed around a cast-metal armature, with hammers striking tightly stretched wires — a pounding piece of percussion machinery as much as an instrument of personal expression. Not for nothing was it once called the Hammerklavier.

It’s precisely this hidden mechanical history that Cage brought out by reinventing the piano, when he “prepared” it with metal screws, bolts, and other factory products, revealing it anew as the percussion instrument it had always been, thereby changing its fundamental auditory qualities. (Watch Jesse Myers play Cage’s Sonatas and Interludes, a cycle of twenty pieces for prepared piano, composed in 1946-48.)

In another strategy for dealing with his massively imposing significant other, Cage could cut it down to a manageable size, by using a toy piano. He thereby further diminished the autonomous status of the instrument whose most prestigious manifestation is called a “concert grand,” making it instead a concert mini, with decreased powers to contest the keyboardist. (Watch Zitong Wang play Cage’s Suite for Toy Piano.)

In addition, of course, Cage could simply overrule his partner’s ability to be heard by instructing it, in the sacrosanct written score, to remain silent, in 4′33″ — a little masterpiece of passive aggression. Despite the performance directive, Tacet, given throughout, some versions of the sheet music include time signatures (usually 4/4) as well as expressive tempo indications (such as Adagio), which could be taken as a rather cruel joke at the mute piano’s expense.

•

Radical though Cage’s efforts to dominate the physical piano were, it’s evident (as in the video of Sonatas and Interludes) that the instrument’s visible exterior remained inviolable. Its immaculately polished wood still conformed to elitist concert propriety.

When Paik, carrying on from Cage, comes to exert his own power over his piano-partner, control turns into something that looks more like abuse. A review of Paik’s Hommage à John Cage: Music for Tape Recorder and Piano (1959), presented in Düsseldorf, described how this beloved classical object was now being placed in physical jeopardy:

On top of the ladder sat the poet Helms, reading the score from a roll of toilet paper. Beneath him were the instruments: two pianos (one of which had no keys), tape recorders, tin cans with stones, a toy car, a plastic train, an egg, a pane of glass, a bottle holding the stump of a candle, and a music box. The audience was urged to be careful: Stand back, please! The cries of twenty distressed virgins rang out from the tapes, then came the WDR news broadcast. (. . .) In the fourth movement, the finale furioso, Paik ran about like a madman, sawed through the piano strings with a kitchen knife and then overturned the whole thing. Pianoforte est morte. The applause was never-ending.

An intense audio-only recording gives an ear-witness account of what the event sounded like. This 4-minute audiotape from the raucous Hommage was rediscovered in 1999 among the many then-uncatalogued items in Paik’s Mercer Street loft; it was released along with other early tapes on a commercial CD by the Sub Rosa label in 2001. (When the recording was made available, in turn, on YouTube after Paik’s death, a visual “realization” was added.) As a disembodied soundtrack on its own, the audio artifact in some ways makes the piece even more disorienting, more of an intimidating rampage, than the written account alone might suggest.

And things got more violent later on. At Paik’s first major solo exhibition, “Exposition of Music — Electronic Television” (Wuppertal, 1963), in a spontaneous action, Joseph Beuys destroyed one of the pianos on view, which Paik kept in the show in its ruined state.

Klavier Intégral

The remarkable Klavier Intégral, a milestone in Paik’s journey from musician to video artist, is the only survivor of the four pianos in “Exposition of Music — Electronic Television.” It had a prior history: it seems to have been one of the two pianos in Hommage à John Cage (presumably, the one with keys); it appeared again at a famously chaotic event in Mary Bauermeister’s Cologne studio in 1960 (recounted in the book under review); and finally, Paik prepared it in 1962-63 for his solo show in Wuppertal. That history is encompassed by the work’s broad officially assigned date of 1958-63.

Over those years, Klavier Intégral came to be festooned with what Paik’s assistant Tomas Schmit listed as “a doll’s head, a hand siren, a cow horn, a bunch of feathers, barbed wire, spoons, a little tower of pfennig coins stuck together, all sorts of toys, photos, a bra, an accordion, a tin with an aphrodisiac, a record player arm.” Catalogue contributor David Toop adds to the list “hidden devices activated by individual keys, such as a transistor radio, a hot-air fan, film projectors, a siren and a switch to control the lighting for the entire room.”

Many of the things on Schmit’s list have what might be called sentimental value — toys, doll’s head, bra, tin of aphrodisiac — and tend to sexualize the piano as an object of the artist’s affection, taking us back to Albright’s insight about instrumental partners. The items could be said to constitute evidence of a fraught spousal relationship. We respond to its long-suffering condition, even as a static object.

In contrast, the objects added by Toop’s list are all mechanical devices, run by electricity and activated by individual piano keys. So in addition to displaying intimate memorabilia, Klavier had also become a switchboard for running such sound sources as a radio, a fan, and a siren, as well as turning the house lights on and off. Intégral indeed. The growing dominance of the current-driven items built into Klavier tells us where Paik had arrived, late in his involvement with the piano as an enhanced acoustical instrument, before he moved definitively into fully electrified — that is, video — work.

Although the many dynamic sound components from its glory days are deactivated in the exhibition gallery, the piano — now as silent as 4′33″ — still carries an aura of mystery, evoked by Jonathan Jones:

One early work, in the Paik show, is mysteriously moving in a way that exposes the ephemerality of a lot of the stuff around it. Paik’s Prepared Piano from 1962-63 is what survives of a series of instruments to which he added objects along lines inspired by Cage. Its upright wooden body is deliberately scratched and battered, its keys covered in strange stains. It is sad and pungent. It has become, over the past six decades, a great sculpture.

The assessment of its power rings true. But I think the inference to be drawn from Klavier Intégral is not so much that it makes Fluxus’s ephemerality look bad by comparison. Rather, I believe, this vibrant sculpture is, in fact, a monument to ephemerality. It’s the very incarnation of music in flux. Alas, we have become deaf to its music because in a museum setting, its flux is arrested. In the Whitney’s 1982 Paik catalogue, Dieter Ronte, then the director of the Museum Moderner Kunst in Vienna, lamented that as an object in his museum’s collection, the clamorous Klavier had been “reduced to a static visual existence,” because visitors could not hear it played.

Since then, however, its home museum has made available an 8-minute video showing what Klavier Intégral sounds like in action, in a demonstration piece, For Nam June Paik’s Piano by Manon-Liu Winter, recorded in 2009. The performance puts before us the live Klavier, with everything it’s got. Its features thereby become more legible as evidence of all it has seen and lived through in its vexed partnership with Paik. For example, in one of the video’s startling close-ups, we may be surprised that the pianist’s fingers are forced to skirt dangerous coils of barbed wire, until we remember that this object was reaching its final form in (West) Germany little more than a year after the construction of the Berlin Wall.

Watching this multimedia apparatus up close now, with its bare flashing bulb, transistor radio, and supporting circuitry, it begins to suggest what “wires and lights” in the big box of a piano console could do, in the form of a kinetic sound sculpture.

Its progeny includes the player-piano and TV hybrid from 1993 now in the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Thirty years after Klavier, this untitled piece looks back on how Paik had moved through the portal of music into the world of video. Late in his active career, he now grants the piano-as-object a well-deserved encore, and lets it catch up with the technological times by “playing” fifteen televisions. A fascinating video presentation by MoMA media conservator Glenn Wharton demonstrates what a tricky multimedia act that was, and what a challenge it is to preserve.

Viola d’Amore

Amid the mayhem of Paik’s Fluxus-era attacks on the piano, it’s quite remarkable that he could still exploit the instrument’s lyrical power in his early video Electronic Moon, #2 (1969), a collaboration with experimental film and video maker Jud Yalkut. Accompanied by a straightforward, unaltered performance of Debussy’s Clair de Lune, the shimmering moon, which may at times resemble a soccer ball, goes through a number of visual metamorphoses, leading up to the arrival onscreen of Paik and an anonymous woman.

Paik’s brand of lyricality can also be seen with the other musical instrument he transformed on his way to the more strictly video work — the cello — in his collaboration with the Juilliard-trained Charlotte Moorman. Not unlike Electronic Moon in this respect, his liaison with the cello shows marked tenderness amid palpable sexual tension.

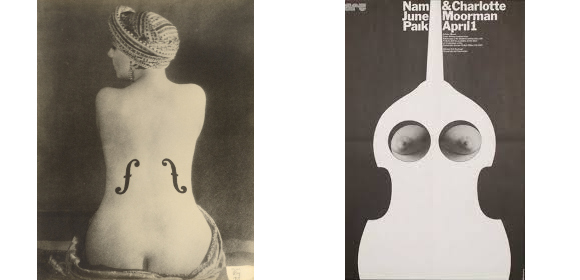

A precedent for this treatment may have been Man Ray’s Le Violon d’Ingres (above), which places on a woman’s back the scrolling f-holes from the front of the stringed instrument. In a kind of neo-surrealist twist, the Paik/Moorman performance poster, too, asserts the shape of the instrument as female, by showing Moorman’s breasts through her cello’s bodily silhouette.

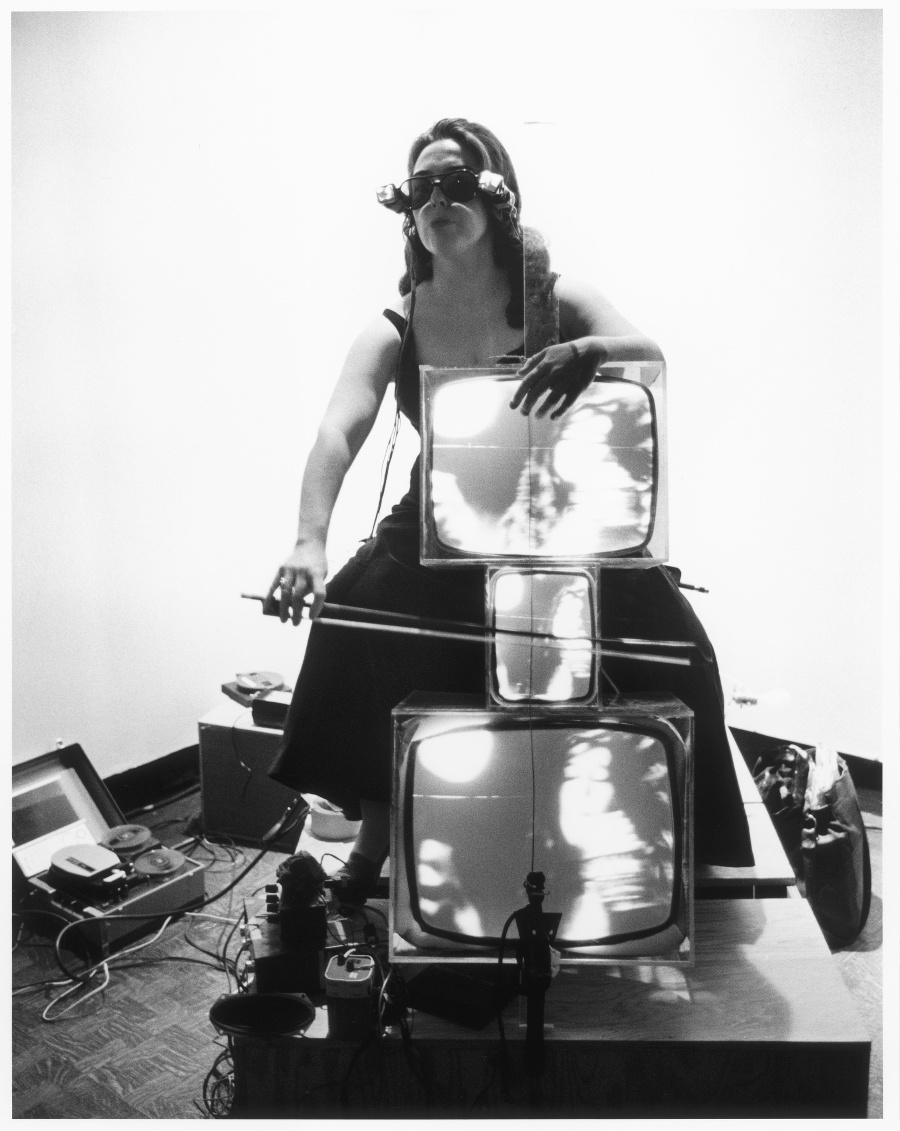

The three of them — Moorman, Paik, and the cello — made up a ménage à trois. Sometimes, Moorman played a conventional acoustical cello, while wearing Paik’s TV Bra (below). Other times, she played Paik’s back as the body and fingerboard of a surrogate cello, bowing across the single string she pressed against his spine.

Most significantly for the future, she played Paik’s breakthrough work, Concerto for TV Cello and Videotapes (1971), which took the idea of the instrumental other in a new direction. A concerto is by definition a musical score bringing together a soloist and an ensemble. In this instance, the solo instrument is the cello, and the ensemble is the videotapes.

Documentary footage lets us see the piece in performance. In this clip we glimpse the intimacy of the collaboration. Moorman moves the undulating bow with her right hand while the fingers of her left hand depress the strings on the fingerboard; she plays some phrases arco, others pizzicato; occasionally, she slaps the strings. And while she’s absorbed in her performance, the TVs respond to it, fulfilling their role as the accompanying ensemble. They do this by carrying images of her in performance, and “playing” them back to her, and us, like a cello theme with video variations. But the TVs respond to the cello in a most disorienting manner, vertiginously rotating their images of it within the screens — an effect of delirious amour fou.

Recalling the trope of lovers “making beautiful music together,” consider Paik’s words from a 1975 interview (published in French, translated in Nam June Paik: Becoming Robot, Asia Society, 2014):

What was most interesting was the intercourse (les rapports) between the body of Charlotte Moorman and the TV set. When two Americans like Moorman and TV make love together, you can’t miss that.

So it was actually a ménage à quatre, as the two artists ultimately acknowledged the TV as the fourth, much-loved partner — a development charged with ramifications for Paik’s subsequent career.

•

We’re fortunate to have this and other recordings, because these events marked a significant change. Concerto for TV Cello and Videotapes confirmed Paik’s decisive shift — from (or through) musical instruments to his new instrument: the video screen.

He would play it like the virtuoso he was for the rest of his life.

(March 2021)