James Leggio

It’s not as dreadful as some may fear. Indeed, DeMille’s 1927 silent epic is actually quite enjoyable to watch. Still, it should be noted that a lot of the pleasure comes from the decidedly non-biblical episodes that embellish the gospel story as told here.

The scenario, by Jeanie Macpherson, is marked by numerous oddities, among them the fact that many large, crucial pieces of the gospels have been left out. Despite a running time of more than two and a half hours, there’s no Nativity here, no Flight into Egypt, no Herod the Great, no baptism in the Jordan River, no Sermon on the Mount, and, oddest of all, no Ascension. With what’s left in, the biblical chronology is often scrambled, as familiar events take place out of order or in the wrong locations.

Although quotations from the gospels are scrupulously cited by chapter and verse in the title cards, much of the rest of the storyline often amounts to a free improvisation from the screenwriter’s imagination. For instance, Jesus visiting another carpenter’s shop and discovering a cross being fabricated there does make a kind of bizarre sense, but has no biblical authority. Even stranger, a bogus affair between Judas Iscariot and the high-living courtesan Mary Magdalene has been invented for “love interest.” Other fabrications have an unfortunate effect on the film’s tone: the Magdalene’s imperious cry “Harness my zebras!” may evoke unwanted laughter. (When they arrive, her zebras get a glamour close-up reminiscent of the chariot racehorses in Ben-Hur.)

With all this in mind, it’s hard to fathom why an Amazon online reviewer wrote: “I believe this is one of the most scripturally accurate of films I have seen outside one that has been sanctioned and produced by a religious affiliation.” And yet, the film’s considerable creative license yields certain benefits. When retelling such a numbingly familiar story, there needs to be something distinctive and striking about how the material is reshaped. For instance, Nikos Kazantzakis’s revisionist novel The Last Temptation of Christ (1955) takes a deliberately non-gospel approach, emphasizing Jesus’s sheer visceral revulsion at his looming sacrifice, and gives the story a new slant, a different, alternative account of how the Passion could have turned out. In a less radical way, the jumbled script of The King of Kings, whatever one may think of it, does offer a lively reboot of the biblical narratives.

Undeniably, some of the invented bits are little masterstrokes, such as having the crowd of witnesses at the Crucifixion include a heartless, gawking spectator who has had the presence of mind to bring along a bag of snacks — like eating popcorn at a movie. And, touchingly commiserating with the Virgin Mary, the distraught mother of one of the crucified thieves gestures toward her own son, saying, “That one is my boy.” These inspired moments of showbiz flair may be preferable to the sanctimonious piety of George Stevens’s The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965), where the dialogue is virtually a tissue of familiar quotations, reverently recited with deadly sincerity.

DeMille’s admirable cast makes the most of the script’s deliberate anomalies. Ignoring the accepted view that Jesus was about thirty years old at the time of his death, H.B. Warner has the face of an older, sadder Jesus; he was fifty when the film was made. He gives a surprisingly naturalistic performance and is comfortable with some lighter touches that exist only in the gospel according to Macpherson. The charming, invented scene of him “healing” a little girl’s broken wooden doll — after all, he was a carpenter — offers a gentle moment of humor rare in this kind of film. Joseph Schildkraut creates a dynamic and effective Judas; with his agonizing self-doubt, not to mention his matinee-idol looks, which give a certain credibility to his make-believe affair with the Magdalene, he almost steals the picture. Ernest Torrence makes a strong physical impression as Simon Peter, even as he proves endearingly bumptious by shrugging his shoulders at Jesus’s more cryptic directives. Rudolph Schildkraut (Joseph’s father) plays the high priest Caiaphas as a caricature, in unsettling scenes of blatant anti-Semitism that are hard to watch; in this case, unfortunately, that’s an all too accurate account of what’s in the gospels themselves.

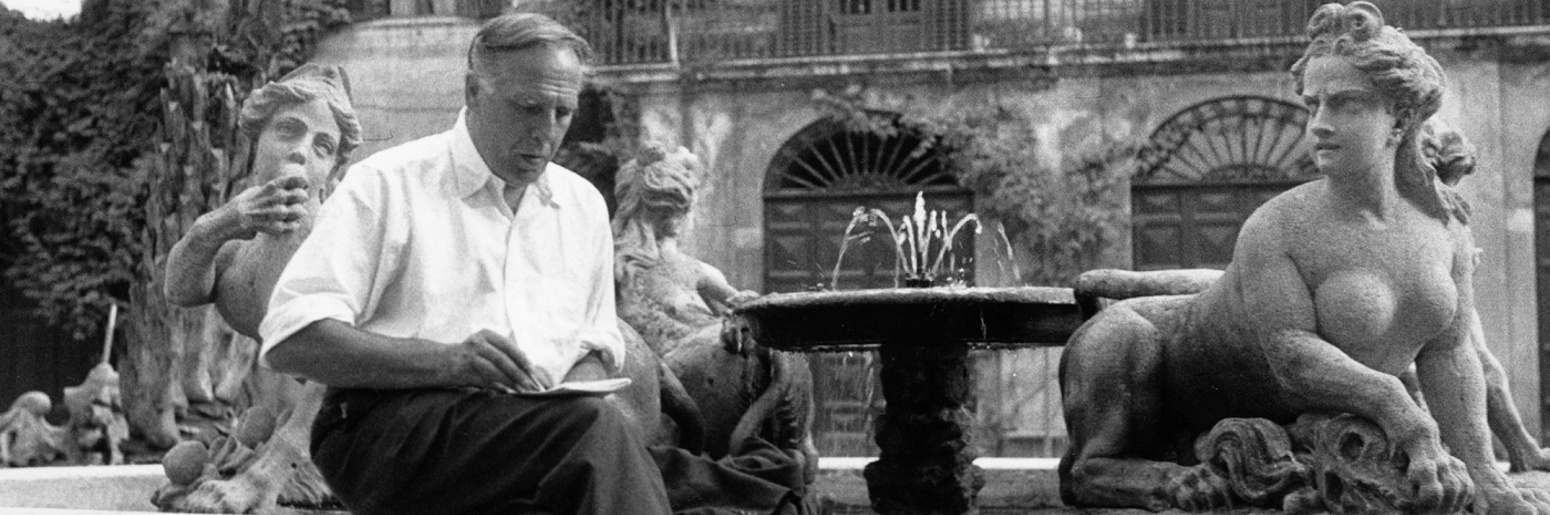

The film also offers many visual pleasures, which help make the invented material seem more plausible. The production design and photography are as good as one could hope for (IMDb credits Mitchell Leisen with art direction and J. Peverell Marley with cinematography). The set for the Temple of Jerusalem is splendid; publicity footage of DeMille with D.W. Griffith during this time perhaps suggests a wish to rival what Griffith had achieved in the magnificent Babylonian temple sequence in Intolerance (1916).

On a more intimate pictorial level, the dove wranglers on the set must have been working overtime, as we see these distinctive white birds throughout the film. They first appear in shots of the Virgin Mary, presumably recalling the dove of the Annunciation, and they flutter through many other key scenes as subtle reminders of an otherworldly presence, even as their flight enlivens some necessarily static camera setups.

On a technical level, the bookend two-color sequences, one at the beginning and one near the end, must have astonished the eye at the premiere.

Some of the more memorable visual effects are devoted to Jesus himself, including one of the most striking entrances any film star could ask for: Jesus’s first appearance. His entrance is deliberately delayed for quite a while. He is absent from the opening scene, in the Magdalene’s house; and in the following scene, set outside a humble home where he is hidden indoors, as he performs his cures off-stage. He remains totally out of view until — in the subjective shot seen through the eyes of the blind little girl as she is miraculously cured — he slowly comes into focus as the first sight the child has ever seen. As the title card reminds us, “I am come a light unto the world.”

The current Criterion DVD edition helps make the best possible case for the film. The color sequences have been carefully restored. And the flowing 2004 score provided by silent-film master composer Donald Sosin lets the viewer ride over the rough spots and discontinuities in the plotting, without dipping into the maudlin religiosity afflicting so many biblical epics. The DVD also includes a re-creation of the original orchestral score, which, with its overly emphatic eruption of Handel’s “Hallelujah” Chorus, lets you imagine the popular religio-musical taste of the time of first release. There’s a movie-house score for organ as well. (The archival footage with Griffith is on the disc to boot.)

Most of all in this film — with its heady mixture of gospel text and imaginative embellishment — it’s fascinating to see how Jesus’s final days were being portrayed in popular culture ninety years ago. Times change, if slowly. As recently as 1961, in Nicholas Ray’s remake of The King of Kings, it was reportedly deemed necessary, for the sake of decorum, to shave Jeffrey Hunter’s armpits before shooting the Crucifixion scene. Compare the reticence of that film with Martin Scorsese’s passionately heretical The Last Temptation of Christ (1988), based on the Kazantzakis novel, or with the unremitting brutality of Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ (2004). Nonetheless, the reverent retellings do live on, most notably in Risen (2016) — in that instance with the detective-story twist of a Roman tribune, played by Joseph Fiennes, searching for hard forensic evidence of the Resurrection.

(November 2017)

l am 73. This is the first “Jesus movie” I’d ever seen. During the 1950s I looked forward to watching it on TV every Easter. As a Catholic I wasn’t supposed to be watching it, apparently due to heretical aspects, probably such as you mentioned. So I “sinned” on Easter Sunday. So what?! I STILL like this one the MOST!/Michael