James Leggio

The printed score for Mozart and Da Ponte’s opera Don Giovanni (1787) calls it a dramma giocoso, or “humorous drama.” Nonetheless, comic though it very often is, its humor can be cutting, even cruel. Some jocund dialogue passages between Don Giovanni and his servant Leporello make light of a father who died defending his daughter from assault. Other comically pointed interludes mock a betrayed promessa sposa seeking marital justice. And the work applies a certain patronizing humor as well to a peasant bride relentlessly pursued by a nobleman who uses his wealth and social status as leverage.

Maynard Solomon put his finger on this most problematic aspect of Don Giovanni and Mozart’s other comic operas in Mozart: A Life (HarperCollins, 1995):

Although Don Giovanni commits an incidental murder. . . the cardinal crimes in the Da Ponte operas . . . are those aimed against virtue, in the first place seduction and rape. Indeed the threat of sexual violation is central to all of Mozart’s opera buffas and singspiels from Zaide to Die Zauberflöte. . . . The threat of seduction or rape provides a backdrop of menace in these operas, which is quite at odds with their comic surface. And the ambiguity in the range of feminine responses to sexual threat adds another level of unease to the narrative tension.

With the growing public recognition, over the last fifty years or so, of how deeply these “cardinal crimes” infiltrate the complex, ambiguous fabric of Don Giovanni, the title character has increasingly fallen from grace with audiences. Though as recently as the 1950s and 1960s he could still be thought of as a high-living romantic adventurer, since the 1970s he’s widely been performed as a ruthless criminal. Notably, Teddy Tahu Rhodes was dressed to kill, in an outfit of leather boxers, boots, and cape, designed by Carl Friedrich Oberle, in the Sydney Opera House production of 2005.

Which raises a question: Since we have become more anxious than ever about scenes of sexual predation being presented for an audience’s entertainment — and especially now, after the revelations of the #MeToo movement that began to erupt in 2017 — just how does an opera company these days go about staging a highly problematic “humorous” drama from the eighteenth century that still draws blood in the twenty-first?

We can begin to explore Don Giovanni’s contested status on the present-day stage by first going back in time, to an era well before the Don’s fall from grace. What did things used to be like in this role’s salad days?

Don Giovanni, Then and Now

In the middle decades of the twentieth century, before the character’s fall, the Don Giovanni singer of choice was Cesare Siepi (1923-2010). His great international success in the part may come in one way as a surprise since, as a true basso cantante (or “singing” bass), he had a much darker, heavier voice than did the many baritones associated with the role in that era, such as Tito Gobbi and Eberhard Wächter, which you might think would put him at a disadvantage in a light, airy piece like the famous Serenade. (Compare audio clips of Siepi, Gobbi, and Wächter in that aria.) Yet with his elegant bel canto phrasing and powerful stage presence, Siepi could make the Don seem like a dashing, seductive lifeforce, with more gravitas than a baritone could muster.

As an obituary for Siepi in the Guardian in 2010 recalled:

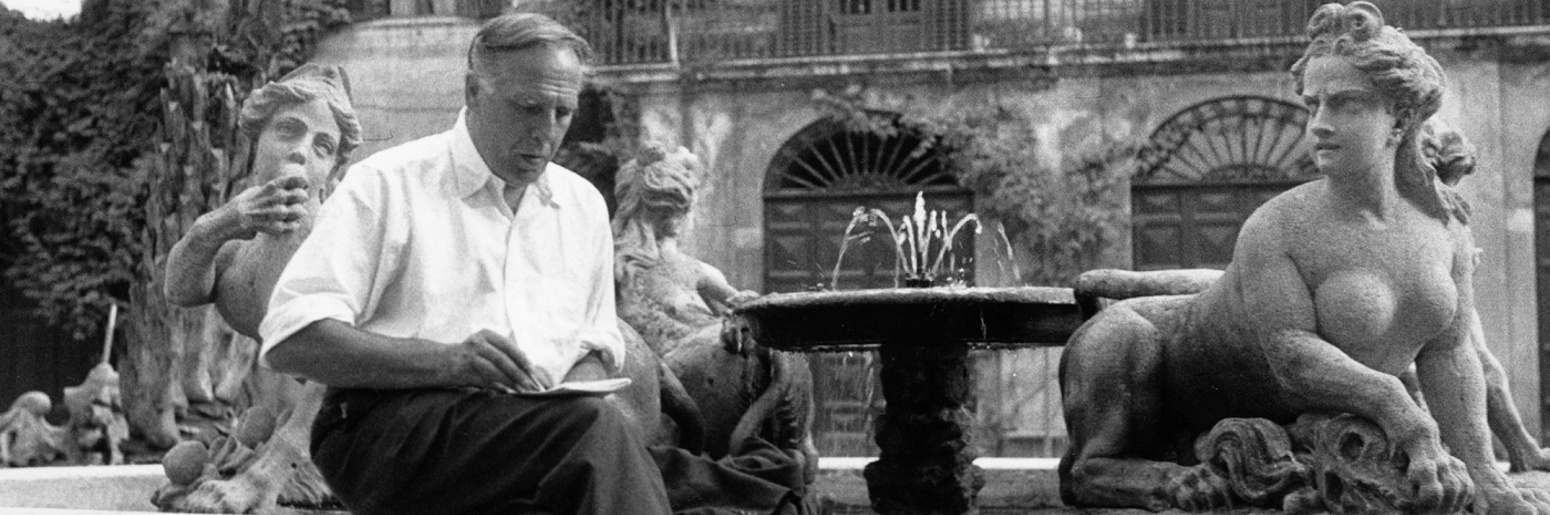

During the 1950s and 60s, Cesare Siepi, who has died aged 87, was the most sought-after of Italian basses, renowned for his Don Giovanni, a role he undertook in most of the world’s major houses. He was indeed the natural successor in the part to the legendary Ezio Pinza, and like Pinza he graced the stage of the Salzburg Festival with his portrayal. . . . There is a permanent record of the occasion in the film made at the festival in [1954] (now available on DVD), with Wilhelm Furtwängler conducting Mozart’s opera. In it, as at Covent Garden a few years later in Franco Zeffirelli’s famed production, Siepi held the stage as a handsome figure, in the mould of Errol Flynn with the attendant sex appeal, although the interpretation overlooked the more saturnine side of Giovanni’s nature so prominent in today’s performances of the part.

The obit here alludes to the charismatic, and quite unobjectionably moral, swashbuckler portrayed by Errol Flynn in the Warner Bros. film Adventures of Don Juan (1948), which fixed the Don’s image in popular culture for a generation. But this mainstream Hollywood Don Juan was simply a misunderstood good guy, with little or no trace of Giovanni’s deeply shadowed undercurrents.

Only since the 1970s, an era marked by the women’s liberation movement, has the saturnine, more troublesome side of Mozart’s Don, mentioned in the Guardian obituary, taken general hold. Even seemingly lighthearted numbers, such as the popular Champagne aria, have in feminism-aware times come to look a lot less charming and a lot more obsessive than they did in Siepi’s day. Elaine Sisman points out how this aria has always tended toward disorder, but now more ominously (see her influential essay “The Marriages of Don Giovanni: Persuasion, Impersonation, and Personal Responsibility,” in Simon P. Keefe, ed., Mozart Studies, Cambridge, 2006):

The chaos of unordered dances at the ball is embodied and forecast in “Fin ch’han dal vino,” even in the older performances of this aria that show the Don as a pleasure-seeker rather than an obsessive man in the grip of compulsion.

She adds in a footnote:

Compare Cesare Siepi, conducted by Furtwängler in the film made of the Salzburg Festival in 1954, with Rodney Gilfry conducted by Nikolaus Harnoncourt at the Zürich Opera House in 2001. Tempo is only one of the many differences between them.

Watching those two performances, the half-century between them becomes immediately obvious. (Watch video clips of Siepi and Gilfry singing the Champagne aria.) Although the Salzburg film looks technically limited, even primitive, when compared to the Met’s slick “Live in HD” shows beamed to us today from Lincoln Center, we can nonetheless be caught up in Siepi’s exuberant, carefree manner — and effortless vocalism — as opposed to Gilfry’s off-putting maniacal grin and eye-popping, cokie stare. Which one would you want to have a drink with?

How the Don was once viewed, in the Siepi era of the 1950s and 1960s, versus how different he seemed to writers by the late 1970s, finds striking expression in Catherine Clément’s book Opera, or the Undoing of Women, first published in 1979. She writes of Don Giovanni’s fall from grace through her own experience as an operagoer. At first, in her youth, she could not resist him:

Who will give me back the Don Juan of my youth, the pure, blind love imprisoned in fantasies my men have? As a girl I could not resist. Sometimes Zerlina, sometimes Donna Anna, sometimes Donna Elvira. I gave in while defending myself, “vorrei e non vorrei.” I want to and I do not want to: I sought vengeance, impressively, for a trifle, fantasizing the supreme offense of rape that is always on the horizon of a girl’s imaginary: I had a mystical forgiveness, pursuing the beloved with charitable parables.

But then her recollections take a different turn, as all the air suddenly goes out of the fantasy:

I remember one day at the Opera. The stage was immense. . . . Don Juan, gesturing grandly with his cape, caught his foot in a guitar, and came crashing down, ludicrously, head over heels, down the huge staircase on which he was delivering his famous serenade . . . this is the image my ears remember . . . Don Juan’s ass rolling down the stairs: all the champagne seductions and lavish splendors of this rebel hero are gone. No, Don Juan is not to haunt my musical universe.

All his former splendor gone, nowadays we are left not with a “rebel hero,” but just a marauding hunter. Even the most entertaining musical numbers, such as the one promoting effervescent “champagne seductions,” become tainted: the lavish dispensing of sparkling wines at the Don’s parties now turns champagne into a gateway drug softening up the unwary for molestation.

An audience member looking through a present-day #MeToo lens sees not only a predator pursuing his prey, but one who can also sometimes incite unwarranted mirth along the way, at a discarded victim’s expense. Don Giovanni has thus seemed to become in some ways, since the 1970s, a smaller and less generous work, in its protagonist’s cold, sardonic contempt for those he wounds.

The Advent of Director’s Theater

Times have indeed changed. And so, what now shapes a viewer’s sense of right and wrong in this old tale of a rake’s comeuppance?

The answer, in a word, is “staging.” To a great extent, our moral compass is, for better or worse, imposed on us by the now all-powerful stage director. For the years after Siepi’s heyday witnessed the global rise of Regietheater, or “director’s theater,” its onset marked by Patrice Chéreau’s epochal restaging of Wagner’s Ring at the Bayreuth Festival of 1976, the cycle’s centennial year. There, memorably, Chéreau took the three Rhinemaidens guarding the gold at the bottom of the primordial river and turned them into three sex workers prowling their turf down by the hydroelectric dam.

In this freewheeling new theatrical world, Don Giovanni too became less about the vocal feats of superstar singers, and more about a director’s radically novel “concept” of the piece.

To cite just one example of a director overriding Don Giovanni’s libretto as written, and substituting a different action: Ivo van Hove, in his 2023 production at the Metropolitan Opera, simply eliminates the formal fencing duel between the Don and the Commendatore, always one of the defining moments in the drama. Instead, Giovanni just takes out a pistol and shoots the unarmed old man. It’s plain murder. His sheer contempt for his victim makes Giovanni a mere villain, by jettisoning the trial-by-combat code of honor that Mozart and Da Ponte had allowed him to observe toward the Commendatore in the written scene. Van Hove’s take on the action, however, with its firearms trick, seems closer in spirit to the familiar film scene of Indiana Jones offhandedly shooting the inconvenient swordsman who confronts him.

Clearly, we are in a post-heroic period of the opera’s history. Indeed, the tale of its “hero,” or antihero, may no longer be the only, or even the most compelling, story Don Giovanni has to tell.

In what follows, therefore, let’s get away from the too-familiar focus on Giovanni himself. Instead, let’s look closely at the three women — Donna Elvira, Donna Anna, and Zerlina — who are his targets, and ultimately his adversaries. And let’s consider how they are now treated: not so much by Giovanni himself, but rather by that postmodern puppet-master, the stage director.

Just how does the director pull the strings of the dramatis personae? If one director can put a gun in the Don’s hand, what might other directors do with the aggrieved Elvira, the traumatized Anna, or the adventurous Zerlina?

The Bitter Tears of Donna Elvira

The laughs during the servant Leporello’s popular Catalogue aria, sung for Donna Elvira’s benefit alone, have a sharp edge. The truth hurts: it is, after all, an aria with an agenda. Elvira wants to know why Giovanni abandoned her — after, as she pointedly reminds him, “you declared me your bride.” (Elvira, says Sisman, “is in fact the victim of a clandestine marriage, a detail not noted in the voluminous literature surrounding the opera”: an “irregular form of marriage” from which “the Church never withdrew its approval.”) Giovanni blandly asserts that he had his reasons for leaving her, but he dares not say what they were, since he had simply exploited clandestine-marriage status as a step to seduction. So instead, he forces Leporello to be the one to speak, if only to shut Elvira up while the Don himself sneaks off:

Giovanni: If you don’t believe me, believe this trustworthy gentleman.

Leporello: (Except the truth.)

Giovanni: Come here and tell her something.

Leporello (aside to Giovanni): And what am I to tell her?

Giovanni: Yes, yes, explain everything.

Significantly, Leporello mutters under his breath the Italian expression “salvo il vero,” meaning Elvira might best believe anything “except the truth.”

Following up, he spouts some temporizing blather about how a square is not a circle. But then he decides to try out il vero after all. He truthfully enumerates to Elvira his extensive written catalogue documenting his master’s seductions — in Spain alone, one thousand and three — of which she is neither the first nor the last. Presumably, as a single digit within this vast sum total, she is supposed to be silenced by sheer math. (Watch Ildebrando D’Arcangelo sing the aria at the Theater an der Wien in 1999.)

Yet the Catalogue aria represents a strange move on Leporello’s part. For one thing, it blows Giovanni’s essential cover story as a supposedly proper, respectable gentleman in his community. For another, the aria tips off Elvira that a rampaging libertine is operating on a dangerously vast scale, cutting a wide swath through women of every rank, age, and condition — almost as if he’s a viral human epidemic.

Nonetheless, Mozart accompanies many lines in the aria with laughing woodwinds.

Director Jonathan Miller edited the book Don Giovanni: Myths of Seduction and Betrayal (Schocken, 1990) shortly after staging Don Giovanni at the English National Opera. As he wrote in his introduction, during the eighteenth century “women who fell from the position of honorable chastity and who failed to have their sexual conquest subsequently sanctified by marriage sank into a sort of death in life — a limbo of exclusion from society, of dishonour and disgrace that very often led to suicide.” Miller goes on to explain the ramifications of this history for the Catalogue scene between Elvira and Leporello:

In light of such evidence, it is difficult for Leporello to perform the catalogue aria in the usual mood of unbridled merriment. In rehearsing the scene with Elvira, the knowledge that such a long list of amorous conquests implied a short, or perhaps not so short, appendix of tragedies led us to sadden the end of the song, as if Leporello becomes infected by Elvira’s despondency and sees, perhaps for the first time, that he has been the unwitting but nonetheless culpable assistant of a truly deplorable enterprise. . . . It is not difficult to visualize the dank morgues in which so many of the despairing victims of the Don’s delight yielded up their post-mortem secrets.

For us today, it is the Don himself, and not his victims, who has fallen into “a limbo of exclusion from society, of dishonour and disgrace.” Miller as director thus shows himself to be Elvira’s supporter, praising the way she can make Leporello face his master’s underlying cruelty.

Nailing down the case against Giovanni, scholar Elaine Sisman shows how the three women undercut his criminal modus operandi:

. . . what might be called Don Giovanni’s Ur-assumption [is] revealed to be no longer valid: that the social stigma of sexual disgrace will prevent his victims either from calling attention to themselves or from coming forward to seek redress. Two screaming women (Anna and Zerlina) and one satisfaction-seeking woman (Elvira) stand ready to create public scandal and thus color the story irrevocably, moving events out of Giovanni’s control, possibly for the first time, since his career spirals downwards before our eyes.

By the end of Act I, Zerlina and Anna have endorsed Elvira’s accusations of Giovanni with a forceful “Me too.” The women have formed an alliance, unmasked the Don for what he is in the finale of Act I, and set the wheels in motion that will lead to his punishment at the end of Act II.

It becomes clear that the opera’s full original title — Il dissoluto punito; ossia, il Don Giovanni (“The Dissolute Punished; or, Don Giovanni”) — puts first things first: the opera’s true subject is his punishment, largely accomplished through women’s agency.

•

Be that as it may, focusing a performance on the coming endgame of the women’s triumph, as the action unfolds, remains a struggle. On stage, old directorial habits die hard.

For instance, in 2015 the Boston Lyric Opera put on what it called a “female-friendly” production of Don Giovanni. As quoted in the Boston Globe, the company’s artistic director, Esther Nelson, wanted audiences to now see the libertine “from the point of view of his conquests.” Nonetheless, the Globe countered, “Easier said than done,” for on stage Duncan Rock’s belligerent, muscular Giovanni dominated throughout, while Anna and Elvira remained merely “the usual studies in high dudgeon.”

Not only was there disappointingly less evidence of the women’s point of view than one might have hoped, but the opera company’s choice of advertising teaser line — “Hell hath no fury like a woman scorned!” — complete with exclamation point, seemed to use that superannuated and arguably misogynistic cliché to trivialize Elvira’s complex social dilemma. Thinking herself a married woman, she feels not so much scorned as unlawfully betrayed by a spouse: abandoned, in violation of a marginal but nonetheless socially recognized form of marriage.

Something very striking about Elvira stands in plain sight in the backstory: in recitative she reminds Giovanni that he remained with her for three days after their “marriage” in Burgos. Even such a brief period of domestic fidelity seems wildly out of libertine character for the Don, with his infinitesimally short attention span. As a kind of pseudo-honeymoon, this three-day interlude of sustained intimacy in a sense confirms Elvira’s marital standing. Her status with him remains unique: when Giovanni utters to Leporello the famous line “Hush, I seem to catch the scent of a woman,” it turns out to be Elvira who is approaching. No wonder her scent is so familiar, since he may well have spent more time in her arms than with anyone else in the Catalogue. Such was her hold on him.

Highlighting her role as an agent of the institution of marriage, a sympathetic director can emphasize Elvira’s protecting, at great personal cost, the impending weddings of Anna to Ottavio and Zerlina to Masetto.

Nonetheless, Giovanni’s repeated humiliations of Elvira, framing her as a hectoring virago or calling her deranged and morbidly jealous — continuing right up to the beginning of the damnation scene — do trade successfully on a lurking audience sense of her as what used to be called a “hysteric.” A significant number of people attending the Met’s new production repeatedly enjoyed laughing at her out loud, as a frequent butt of the opera’s humor, when she’s mocked to her face by Giovanni.

Observing the merry audience reception often given to the verbal abuse inflicted on Elvira by Giovanni, Kristi Brown-Montesano asks what she calls a “heretical question” (in Understanding the Women of Mozart’s Operas, University of California Press, 2007):

Could it be that golden boys Mozart and Da Ponte managed to “out-Giovanni” the libertine himself, manipulating us with words and music into enjoying a sadistic display of power over a helpless woman?

Donna Anna: Reporting an Assault

If the patronizing stereotype of the “scorned woman” has proven resilient in the directorial management of Elvira’s anger, so too has a different typecasting category sometimes been imposed on Donna Anna in her grief.

Mozart and Da Ponte left it to our imaginations to figure out what happened between Anna and Giovanni just before they emerge from her family residence. The stage directions say “She enters, holding firmly onto Don Giovanni’s arm, as he tries to shake her off,” and in the struggle she cries out, “Like a wild avenging Fury I’ll pursue you to the end.” Soon her father comes to her aid and is killed.

For reference, look at this opening scene in the 1954 Salzburg film, which meticulously observes Da Ponte’s stage directions (watch a clip, featuring Otto Edelmann, Elisabeth Grümmer, Cesare Siepi, and Dezsö Ernster). We cannot know at this point what happened in the minutes before Anna’s appearance on stage. Not until much later in Act I, in the long recitative leading up to her aria “Or sai chi l’onore,” do we hear her detailed account of a masked intruder entering her rooms.

Now here’s the problem: when Anna calls herself “a wild avenging Fury,” a director could take that as license to bring in another aspect of the derisive “hell hath no fury” view of things. Following out the logic of Romantic writer E.T.A. Hoffmann’s well-known short story “Don Juan” (1812), one might claim that Anna is or has been in love with the Don, willingly consented to his advances, and only afterward, in remorse for her father’s death, furiously cried rape.

Anna’s role, as thus rewritten by unseen directorial hands, becomes embroiled in one of the pernicious tropes of what is now sometimes called rape culture: the false accusation.

We see this perhaps most clearly in the 2011 La Scala production of Mozart’s opera. This version tries to imagine for us what could not be seen in Anna’s rooms, in the opera as written. While Leporello the lookout complains outside, Giovanni (maskless) and Anna frolic in her bedroom, relatively unencumbered by garments. Their sharp back-and-forth dialogue, which in other productions represents a bitter, desperate struggle, sounds in this revised context suspiciously like a bit of provocative “talking dirty” in bed. But perhaps the most remarkable feature of this behind-closed-doors reimagining is the role of Anna’s father: he suddenly barges unannounced into his daughter’s bedroom and catches her in flagrante delicto with a stranger. She hides her face in shame when her father looks at her. (Watch a clip from La Scala, 2011, with Bryn Terfel, Peter Mattei, Anna Netrebko, and Kwangchul Youn.)

Stage director Robert Carsen explained the logic of his “false accuser” concept in an interview for the 2017 revival of his La Scala production (watch the interview). There he pays Don Giovanni the ultimate compliment of the director’s profession, claiming that the Don “stage manages” everything in the opera. Indeed, in Act II of this production, Giovanni sits in a director’s chair with his back to the audience and raptly watches (with Elvira’s maid as his guest) the confused events set in train by his exchange of cloaks, and identities, with Leporello. In this telling, the stage director makes himself Don Giovanni’s ally and accomplice: essentially, he anoints the Don as his protégé. While impugning Anna’s honesty on stage, in the interview Carsen also sees fit to apply the words “psychotic” and “hysteric” to Elvira.

Late in Act I of this staging, Anna’s account of what happened with Giovanni in her apartment looks entirely different from what we saw in the first scene. When she starts her narrative, in the recitative before “Or sai chi l’onore,” we’re supposed to know immediately that she’s lying, because her story simply does not match what we saw with our own eyes earlier. (Watch a second clip from La Scala, 2011, with Anna Netrebko declaiming Anna’s narrative.)

Hers is a long, complicated speech, the longest in the opera, and it’s well worth reading carefully, to note the wealth of corroborative detail in her testimony, something investigators look for in a victim’s complaint. (The libretto is here quoted from William Murray’s translation.)

It’s a speech prompted in part by Elvira, continuing her role as the defender of marriage. In the immediately preceding scene (included in the La Scala clip), Anna and Ottavio encounter Elvira and Giovanni, the only time the four nobles appear together without the other characters. Elvira urgently tries to persuade Anna and Ottavio that the Don is not what he seems. The couple, impressed by Elvira’s forthright bearing, together comment, “I’m beginning to suspect.”

Directly afterward, since the intruder was (at least according to the printed stage directions) wearing a mask, Anna now recognizes him by having just heard Giovanni’s voice. When they’re alone, she tells Ottavio:

O ye gods! O ye gods! That man is my father’s murderer! . . . There is no doubt about it. The parting words the villain uttered, his whole voice recalled to my heart that worthless creature who, in my apartment . . .

Ottavio is convinced by her act of voice recognition, though outside of an opera house, where a singer’s voice is their identity, this might seem a shaky form of evidence. He then asks to be told what happened in her apartment, the very thing the audience was not allowed to see at the opera’s beginning. Up to this point, we are in the dark as much as Ottavio is.

It was already quite late when into my rooms, where I unluckily happened to be alone, I saw a man enter, wrapped in a cloak. At first I mistook him for you, but then I realised that I was mistaken.

Anna’s account begins by setting the scene: she was alone, quite late, in her rooms. What does an audience make of her first thought, on seeing “a man enter, wrapped in a cloak,” that it was Ottavio? Had he possibly, sometime in the past, come to her late at night when she was alone and unattended in her rooms? Her initial assumption of a clandestine visit by her fiancé may, for a curious director, seem to pry open the beginning of a question about her life as a betrothed individual.

As she continues, her pinpoint recollection of detail may demonstrate how the second-by-second experience of a terrible event will be forever seared into one’s memory. But it may also remind the eager stage director that Anna has had quite a bit of time since the opening scene to, as they say, get her story straight. Either way, her account of the assault is compelling:

Silently he approached me and tried to embrace me. I tried to free myself but he seized me all the harder. I screamed, but no one came! With one hand he tried to quiet me, and with the other he seized me so hard that I already thought myself lost. . . . Finally my despair, my horror of the deed so strengthened me that by dint of twisting, turning and bending I freed myself of him!

She vividly describes the brute physicality of the struggle: the attacker using one hand to silence, the other to seize; Anna not simply struggling but “twisting, turning and bending.” Unlike some other targets of assault, however, she never has to answer the hostile defense-attorney question, “Why didn’t you scream?” She did scream, but late at night it took some time for help to arrive.

At this point, Anna’s account brings us up to what we could actually see at the beginning of the opera, when she pursued the intruder to the street:

Then I redoubled my screams for help. The felon fled. Quickly I followed him as far as the street in order to catch him, becoming in my turn the pursuer. My father ran out, wanted to learn his identity, and the rascal, who was stronger than the old man, completed his misdeed by murdering him!

Since we ourselves witnessed this street scene, it may seem strange to us, now, that Anna does not mention how her father in fact challenged the intruder to a duel. Another tiny bit of possible doubt embedded in Anna’s factual narrative? The degree of possible doubt can be increased by decisions made in the process of staging. Da Ponte’s printed stage directions tell us that as soon as the Commendatore arrives on the scene, Anna immediately runs into the house and therefore does not witness what ensues between her father and the intruder. Still, directors have felt free to choose their own precise moment for Anna’s withdrawal. In Carsen’s staging, she doesn’t leave until after her father has drawn his sword (slipped out of his walking stick).

The timing at this juncture is important, since manipulating the exact sequence of events makes it possible to argue, for one so inclined, that her account exhibits the bias of “motivated reasoning” (which has been defined, to paraphrase Ziva Kunda’s landmark article, as a process “by which personal emotions control the evidence that is supported or dismissed”). That is to say, Anna’s complete omission of the fact that the Commendatore challenged the intruder to a duel, a challenge she sees in Carsen’s staging, ignores her father’s fatal recklessness and makes Giovanni — who initially refused, twice, to fight the old man — look even worse than he is. Anna can be made to seem unduly “motivated” in her revenge-directed selection of the evidence, and anxious to motivate Ottavio as well.

Finally we learn from her, as the aria proper takes off, that this is not only an account of a crime, but also a call for her fiancé to act:

Now you know who tried to steal my honour from me, who was the betrayer who took my father’s life. I ask you for vengeance. Your heart asks for it, too. Remember the wound in the poor man’s breast, the ground all around covered with blood, if ever in your heart your just anger weakens.

The last line, fearing his anger’s weakening, could be read as a lingering concern about Ottavio’s steadfastness. Given very little to do by Da Ponte’s libretto, the tenor can fade into unaccountable passivity in conventional productions. And no wonder he often seems perplexed: his beloved Anna makes no clear distinction between legal justice and personal revenge.

Despite its occasional internal inconsistencies, the way Anna reports the assault matches the printed stage directions, as well as the staging of the 1954 Salzburg film, at least regarding the part of the action we can see, after Anna and Giovanni emerge from the residence. But because director Carsen has made up his own version at La Scala of what transpired within her rooms, all of Anna’s subsequent testimony in that performance is supposed to ring false, and her account is made to seem like a self-serving fabrication, designed to protect her honor in the eyes of her fiancé.

Anna is made, by the inventive staging, into the epitome of the false rape accuser. Further unsettling her credibility in the testimony scene, set at a church service for the Commendatore, Anna rather inappropriately at first wears the glamorous celebrity-in-disguise dark sunglasses of a Hollywood star. Then too, her frantic flailing through a sea of chairs, in recounting her attempt to evade the assailant, not only contradicts our eye-witness memory of that earlier scene, but also gives an unwonted sense of calculated theatricality to her pantomime, as if she borrowed the chair business from Pina Bausch’s renowned, frequently revived dance piece Café Müller, in which a roomful of straight-back chairs obstructs the dancer.

Still, we have to remind ourselves that what we saw at the beginning of Act I in Carsen’s La Scala staging was only what a director fancies could have happened, or what he wanted to happen, when Mozart and Da Ponte deliberately hid that part of the action from us, with their finely balanced ambiguity. With no witnesses to what occurred within her rooms, the story Anna tells, even as actually written in the libretto and score, could perhaps just conceivably have been forced into such a “she said, he said” stalemate. But Carsen/La Scala completely remove any residual ambiguity lurking in the Mozart/Da Ponte conception, and flatly accuse her outright of lying. The director might as well have sewn a scarlet letter onto her dress.

The choices of most other directors stand at the opposite pole. For instance, the Seattle Opera’s 2014 staging presented Erin Wall as a deeply traumatized Anna, her facial expression blankly despondent. She and Ottavio are here swearing an oath of vengeance against Giovanni, but the damage to her psyche has already been done.

•

Just as we can’t corroborate Anna’s behavior immediately before her entrance, so too do some feel that we don’t know enough about her ongoing emotional life throughout. As Brown-Montesano writes:

Mozart and Da Ponte do not fully expose Anna’s amorous “soft” side, even in her exchanges with her betrothed, Don Ottavio, leading commentators to generate theories about her “real” feelings about Don Giovanni. . . . Since the mid-twentieth century, critics and scholars have frequently asserted Donna Anna’s shameful secret passion as fact, but they have replaced the poet’s [Hoffmann’s] earnest sympathy for her plight with a disparaging cynicism.

Regarding her “soft” side, the new Met/van Hove staging marks a significant advance. Van Hove choreographs their body language to show us an Anna (Federica Lombardi) and Ottavio (Ben Bliss) whose passion generates extremely affectionate, intimate behavior. (Watch a clip of “Non mi dir” from the Met.)

Moreover, Bliss’s unusually virile vocal performance as Ottavio, who wields the ringing coloratura of “Il mio tesoro” as a weapon, to match the sword he’s carrying, makes the tenor for once a credible male adversary to Giovanni.

Zerlina’s Razor

The character Zerlina, in her first scene with Giovanni, faces a rapid-fire strategy of seduction. In recitative, he hustles her along, from flirtatious initial approach, to outrageously ardent flattery, to abrupt marriage proposal, in a few minutes. (Watch their ensuing duet in the Glyndebourne Festival production of 2010.)

And his strategy almost works, not because Zerlina is naïve — far from it — but because she is comfortable with her own sexuality, and possesses a lively sense of amorous adventure. At Glyndebourne, the Cinderella-like moment when Giovanni puts her missing slipper back on her naked little foot tells us where, at first, she thinks this relationship with her Prince Charming is going.

Only Elvira’s timely intervention removes her from Giovanni’s grasp. And from there, disappointment follows. Zerlina’s disenchantment grows after an embarrassing episode wherein the Don again pursues her, but this time while Masetto watches, enraged, from a hiding place. And it is her scream at what may be an off-stage attempted rape that precipitates the frantic finale of Act I.

In Act II, therefore, we can observe a different, aggrieved, and truly aggressive side to her, in an episode few have seen in performances of Don Giovanni: the so-called Razor scene.

As with Ottavio’s aria “Dalla sua pace” and Elvira’s “Mi tradì,” Mozart and Da Ponte wrote the Razor scene for the second staging of the opera, in Vienna in 1788, the year after the first staging, in Prague.

This episode was interpolated into Act II, immediately following the capture and unmasking of Leporello, who had been impersonating Don Giovanni. In it, Zerlina threatens the servant with a razor blade and ties him up.

Kristi Brown-Montesano gives an admirably insightful, detailed account of Da Ponte’s vulgar dialogue for this scene:

. . . Da Ponte gave Zerlina a rather coarse vocabulary and manners in a scene and duet with Leporello added for the Vienna premiere. This interpolated later scene (2.10a) not only shows a more aggressive Zerlina, but the duet skewers the manine theme. When Leporello tries to flatter Zerlina as his master did (“by these your two hands, white and tender, but this fresh skin, have mercy on me!”), she responds by dragging him around by the hair and menacing him with a razor blade. Calling the feckless manservant a “schiuma de’ birbi” (“scum of rogues”) and “mascalzone” (“scoundrel”), she terrorizes him with threats of dismemberment. She wants to take off his head and hair and extract his heart and eyes, bestowing upon him the “reward that comes to he who injures young women.” Shouting to Masetto for assistance, she mutters when she receives no answer, “Where the devil has he gone.” By the duet’s end, Zerlina makes it clear that she knows how to deal with rascals: still armed with her blade, she binds the trembling Leporello to a chair and exclaims, “Joy and delight glitter in my breast. This is the way one handles men.”

To see what all this looks like in action, watch a clip of the Razor scene, again from Jonathan Kent’s Glyndebourne Festival production of 2010, with Luca Pisaroni and Anna Virovlansky. This performance includes some clever directorial felicities that do enter fully into the spirit of the dialogue as written. That is, if turnabout is fair play, Zerlina takes this opportunity to inflict a number of gender-based insults on Giovanni’s stooge and co-conspirator, as if she were avenging what he did, for example, to Elvira with the Catalogue aria and with his support of Giovanni’s subsequent verbal abuse.

Most notably, Zerlina here makes creative use of personal accoutrements. First, after provocatively taking off one of her (modern-dress) nylon stockings in full view, almost as an act of erotic torment against the helpless Leporello, she stretches it out to tie up his legs. Then she removes his belt, loops it around his neck like a noose, and makes it into a leather strop for sharpening her razor, as if she were a barber about to shave him. (Shades of Beaumarchais.) Finally, she opens up the other stocking to shrink-wrap Leporello’s head, distorting his features as if he were a criminal in disguise (which of course he was, in the preceding episode).

Here, agency trumps humor. Perhaps that’s why the scene quickly fell out of the standard performance tradition. The initial audience, in imperial Vienna, may have been nonplussed by the spectacle of superheated female revenge — coming from a peasant, no less, early in the Age of Revolutions.

Moreover, although Zerlina does manage to punish the dissolute one, it’s only in absentia, so to speak, with Leporello as his surrogate. In fact, the three women in the opera find themselves unable to punish Giovanni himself directly.

Finale: The Patriarch’s Return

Although Don Giovanni’s guilt was publicly established by the end of Act I, he remains at large until the last minutes of the opera. The women’s alliance revealed his crimes to all, back in the ballroom scene, but nothing much happens to him as an immediate result, though the Razor scene may suggest a shift in the balance of power. Yet even if Ottavio makes good his promise to go to the authorities with charges of assault and murder, Giovanni’s wealth and social rank may still protect him from prosecution.

Despite the women’s bravest efforts, then, and despite their having proven their case, the state of play remains at a standstill for most of Act II. There the action digresses into numerous mildly comic interludes that do little to advance the main “punishment” plot. Amid the occasional longueurs of Act II, justice is delayed and momentum lost. Perhaps the action as written cannot be expected to entirely escape the eighteenth-century rules of the game, after all, when patriarchy reigned.

Given the governing spirit of the age, it’s not surprising that, ultimately, Giovanni is brought to a final reckoning not by the women alone or even by the community at large, but by one man — who happens to be a dead father.

It’s well known that Mozart’s father, Leopold Mozart, died while his son was writing Don Giovanni. Not entirely surprisingly then, by the 1920s some commentators began to think of Don Giovanni in terms defined by Sigmund Freud, a view that Otto Rank challenged and enlarged upon in his own essay “Don Juan” (1922), written after seeing the opera.

Since then, many interpreters have assumed Mozart’s self-identification with the Don, countered by a father figure. For certain psychoanalytically inclined critics, the whole opera becomes an Oedipal struggle between Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (projected onto the highly talented but mischievous youth Don Giovanni) and his demanding father and musical mentor, Leopold Mozart (projected onto the censorious old paterfamilias, the Commendatore).

Fortunately, with far greater subtlety and insight, Brigid Brophy clarifies the interplay of father and son (in Mozart the Dramatist, Faber, rev. 1988):

. . . in 1787 he faced the obligation of the commission he had accepted in Prague, conscious that it must be his first major work to be carried through without Leopold’s support, and unconsciously holding himself to blame for Leopold’s absence. . . . In these pressures Mozart must have doubted . . . whether he could rise to the occasion; and the Commendatore’s ability to rise . . . even after death must have figured to him as a magic talisman of his own ability to transcend Leopold’s death.

And most remarkably, in this matter of life and death, the crime for which the Don is punished in the end is not so much seduction or even rape: it’s parricide. Giovanni kills a monumental father figure in the first scene, and the dead Commendatore avenges himself — and himself alone — in the damnation scene, without even mentioning his wronged daughter’s name. Only then is Giovanni dragged off to hell. (Watch this scene from the 1954 Salzburg film.)

•

But wait. Even this definitive ending of the rake’s time on earth can be reversed by an ingenious director.

Most astonishingly, in Robert Carsen’s La Scala production, Eros triumphs over Thanatos. At the close of the final “happy ending” sextet, Don Giovanni mysteriously rises again, smirking and smoking, from the land of the dead, as the six other characters slowly sink into the steamy abyss below the stage, upon singing these lines:

This is the end which befalls evildoers.

And in this life scoundrels

always receive their just deserts!

The opera may once have been called Il dissoluto punito, but in Carsen’s staging who is punishing whom?

(August 2023)