The Hours. Composer: Kevin Puts. Librettist: Greg Pierce. Conductor: Yannick Nézet-Séguin. Principal cast: Renée Fleming, Kelli O’Hara, Joyce DiDonato, and Kyle Ketelsen. Production: Phelim McDermott. Lighting design: Bruno Poet. Choreography: Annie-B Parson. Set and costume design: Tom Pye. Projection design: Finn Ross. Dramaturg: Paul Cremo. The Metropolitan Opera, New York, November-December 2022.

James Leggio

To retrace the intriguing backstory of this new opera, let’s start at the beginning.

In 1998, author Michael Cunningham brought out The Hours. Spinning a new, independent novel out of Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway (1925), he enfolded elements of her fiction and life within two other stories, about her posthumous American readers. We are introduced to Virginia Woolf herself, portrayed in England in the year 1923; Laura Brown, in 1949, in California; and Clarissa Vaughan, in the New York City of the late 1990s.

Then, in 2002, Paramount Pictures released a film adaptation of Cunningham’s novel, directed by Stephen Daldry with a screenplay by David Hare and a score by Philip Glass.

And now, based on both the novel and the film, we have the opera The Hours, with music by Kevin Puts and libretto by Greg Pierce, which premiered at the Metropolitan Opera in November 2022.

In retrospect, it seems almost inevitable that the novel and film story called The Hours would ultimately lead to an opera, completing the trifecta. Both the novel and film are, essentially, heavily aestheticized studies in the psychology of suicide, and in fact the leading characters in many of the most revered tragic operas in the repertoire do choose to end their own lives. In some ways, it’s almost a defining feature of opera as an art form. The obvious examples, among female characters, include the chosen deaths of Purcell’s Dido, Bellini’s Norma, Verdi’s Trovatore Leonora, Wagner’s Brünnhilde and Senta, Puccini’s Tosca, Cio-Cio-San, and Liù, along with many others. The list is long for male characters as well: Verdi’s Otello, Gounod’s Romeo, Massenet’s Werther, Berg’s Wozzeck, Britten’s Peter Grimes, and so on. Familiar endings such as these, as for example when Tosca leaps from the roof of a high building or Wozzeck drowns himself, established the expectations that many will bring to The Hours as a serious opera.

Indeed, it’s tempting to reimagine the whole twenty-four-year enterprise of The Hours — Michael Cunningham to Stephen Daldry to Kevin Puts — in terms of music drama. In this essay, I want to entertain the notion that The Hours has in some sense been an opera all along, from the beginning. But this approach can be tricky: the word operatic, in its positive sense, can mean in this enterprise something like “grandly, lyrically expressive”; but it can also mean, in a negative sense, “exaggerated or melodramatic.” There’s a tug-of-war between these two alternatives throughout the cross-media evolution of The Hours.

Above all, such an approach to The Hours suggests itself because there was already a great deal of opera within the published text of Mrs. Dalloway as Woolf wrote it.

And so, to begin, let’s explore opera’s role in Mrs. Dalloway.

Opera in Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway

Since Mrs. Dalloway is very much a novel of everyday surroundings, as experienced by the principal characters, it’s not surprising that pedestrian sounds take up much of its auditory space. The tolling of nearby Big Ben punctuates the action, marking off the passing hours, one by one, that gave Woolf’s story its initial working title as “The Hours.” And the music heard, on the street and in the remembering mind, is often unremarkable.

Yet at the same time, Woolf was intimately familiar with the music of Richard Wagner, having attended performances of nearly all his operas, most of them many times over, including at least four complete cycles of Der Ring des Nibelungen; she saw Tristan und Isolde while writing Mrs. Dalloway. Even as early as 1909, she had noted somewhat jealously, in her essay “Impressions at Bayreuth,” that “we are miserably aware how little words can do to render music.”

A number of scholars have explored Woolf’s use of Wagnerian materials. For instance, Emma Sutton points out in Virginia Woolf and Classical Music: Politics, Aesthetics, Form (Edinburgh, 2013):

Despite the notorious affectivity of Wagner’s music, which Woolf warily acknowledges in works including Jacob’s Room and The Years, “Impressions at Bayreuth” had outlined a conception of music in the abstract as inclusive, as accommodating the diverse autonomous subjectivities of its listeners, a capacity that Woolf attributes to music’s “lack of definite articulation”: “Perhaps music owes something of its astonishing power over us to this lack of definite articulation; its statements have all the majesty of a generalisation, and yet contain our private emotions.”

(I’ll return to the idea of music’s accommodating “diverse autonomous subjectivities” at the end of this essay.)

Sutton follows out the theme of disarticulation in analyzing the well-known but still puzzling episode of the beggar woman who sings in Regent’s Park in Mrs. Dalloway:

The beggar woman’s song in Mrs Dalloway famously confounds listeners and readers, appearing to lack recognisable formal shape or development, seeming ultimately senseless: “bubbling up without direction, vigour, beginning or end, running weakly and shrilly and with an absence of all human meaning”. Language and semantics break down, the sounds rendered as “ee um fah um so / foo swee too eem oo”. The song is a form of Ur-language or Ur-music, a counterpart to similar originary models such as the tonic sol-fa singing method, which the sounds recall, or Wagner’s accounts of the origins of music and language in Oper und Drama and elsewhere, or even his primeval Erda (“Earth”) from the Ring (the voice is “an ancient spring spouting from the earth”).

The critic here alludes to the two scenes in Wagner’s four-opera cycle Der Ring des Nibelungen, in which the character Erda, the earth goddess, appears. In Das Rheingold, amid a dispute over possession of the golden ring, Erda mysteriously rises from out of the earth and warns Wotan, lord of the gods, of disaster unless he relinquishes the hard-won prize. (Watch this scene, from Bayreuth in 1976.) In Erda’s second appearance, in Siegfried, Wotan calls upon her to awaken and, with her all-knowing wisdom, advise him on the fate of his daughter Brünnhilde (Erda is her mother) and the young hero Siegfried, who will soon arrive to set Brünnhilde free. (Watch this scene, also from Bayreuth in 1976.)

•

As Sutton notes, she’s extending the argument made by J. Hillis Miller in Fiction and Repetition: Seven English Novels (Harvard, 1982). There, Miller had apparently been the first to notice that three lines of the Mrs. Dalloway text surrounding the beggar woman’s singing come from an art song composed by Richard Strauss in 1885. Miller wrote:

Woolf has unostentatiously, even secretly, buried within her novel a clue to the way the day of the action is to be seen as the occasion of a resurrection of ghosts from the past. There are three odd and apparently irrelevant pages in the novel (pp. 122-124) which describe the song of an ancient ragged woman, her hand outstretched for coppers. Peter hears her song as he crosses Marylebone Road by the Regent’s Park Tube Station. It seems to rise like “the voice of an ancient spring” spouting from some primeval swamp. It seems to have been going on as the same inarticulate moan for millions of years and to be likely to persist for ten million years longer:

ee um fah um so

foo swee too eem oo

The battered old woman, whose voice seems to come from before, after, or outside time, sings of how she once walked with her lover in May. . . . Woolf has woven into the old woman’s song, partly by paraphrase and variation, partly by direct quotation in an English translation, the words of a song by Richard Strauss, “Allerseelen,” [All Souls’ Day,] with words by Hermann von Gilm. . . . [H]eather, red asters, the meeting with the lover once in May, these are echoed in the passage in Mrs. Dalloway, and several phrases are quoted directly: “look in my eyes with thy sweet eyes intently”; “give me your hand and let me press it gently”; “and if some one should see, what matter they?” The old woman, there can be no doubt, is singing Strauss’s song.

(Listen to Strauss’s “Allerseelen,” sung by Hermann Prey.)

The final stanza of the song, though not quoted by Woolf, is nonetheless suggestive as well. For, as Miller pointed out, on All Souls’ Day the dead rise in spirit and visit the living, much as Peter Walsh and Sally Seton, vividly recalled by Mrs. Dalloway, actually come back into her life, after many years’ absence, and attend her party at the end of the novel.

In the seemingly private, almost esoteric nature of the song the author had implanted within Mrs. Dalloway, Sutton (and a colleague, Vanessa Manhire) find fresh evidence of Woolf’s enduring preoccupation with cultural Wagnerism:

Whether or not we recognise the words of the Strauss song into which these phonemes morph, or perceive echoes of “Träume” from Wagner’s “Wesendonck-Lieder”, a “study” for Tristan, which eulogises the “wondrous dreams / [that] hold my senses in thrall, [so] that they have not dissolved, / like empty bubbles, into nothingness”, is almost irrelevant: such “recognitions” cannot fully explain the song to us or its fictional listeners. As Vanessa Manhire notes, the disruptive effects of the song are extensive and multiple, seeming to halt time and dissolve location (the woman sings “through all ages”).

(Listen to Wagner’s “Träume,” sung by Jessye Norman.)

Like Erda’s appearances, which too “halt time and dissolve location,” Late Romantic pieces like Wagner’s “Träume” and Strauss’s “Allerseelen” represent an enrapturing sound-world of memory and desire familiar to Woolf the music lover.

The significance of Wagnerian (and Straussian) allusions in Mrs. Dalloway should not come as a great surprise. At the time the novel was being written, Leonard and Virginia Woolf, as the proprietors of their Hogarth Press, were setting type for the first book edition in Great Britain of T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, one of the most widely influential statements of modern literary Wagnerism.

•

Like Eliot, Woolf had known mental crisis, and she was able to give creative expression to that experience in the way she invented her own modernist style of writing.

Her misguided “treatment” by an ill-advised medical profession had been disastrous. In 1904, distraught at the deaths of her mother, older half-sister, and father within a relatively few years — what she called “the seven unhappy years” — she had thrown herself out a window, and was institutionalized for a time under the care of the eminent psychiatrist George Savage, who had been a friend of her father’s. She continued to consult Dr. Savage for a decade.

He subjected Woolf to what was called the Weir Mitchell rest cure, designed to treat female “hysteria” cases by means of extended bed rest, inactivity, strict isolation from friends and family, and enforced drinking of great quantities of milk. Hermione Lee, the author of a major biography of Woolf, notes: “Dr. Savage’s application of this system had a powerful effect on Virginia Woolf’s life.” Among the consequences: a lingering fear of medical incarceration.

It was her writing that eventually gave her a way to address the damage done. With his authoritarian conduct and unhelpful ideas about how to treat “nerve” cases, Dr. Savage (and some other practitioners) would be bitterly satirized in the character Sir William Bradshaw, the renowned London psychiatrist in Mrs. Dalloway whose blundering and bullying provoke the suicide of the shell-shock patient Septimus Warren Smith.

By projecting her own medical mistreatment onto Septimus — who, like the author in 1904, leaps from a window — Woolf unknowingly provided the nexus between a man’s suicide and a woman’s that gave rise to the novel The Hours.

Michael Cunningham’s Novel The Hours

In the emergence of The Hours enterprise, much has been made of what Virginia Woolf had to say about her leading character, in the introduction to the second edition of Mrs. Dalloway, in 1928:

Of Mrs Dalloway then one can only bring to light at the moment a few scraps, of little importance or none perhaps; as that in the first version Septimus, who later is intended to be her double, had no existence; and that Mrs Dalloway was originally to kill herself, or perhaps merely to die at the end of the party. Such scraps are offered humbly to the reader in the hope that like other odds and ends they may come in useful.

These “odds and ends” have since inspired a cottage industry based on second guessing her novel, seen in retrospect as a kind of diagnostic premonition of Woolf’s own suicide, in 1941.

Notably, with Michael Cunningham’s novel The Hours, in 1998, Woolf became “source material” for another novelist to appropriate at will. Woolf the actual, historical personage underwent a kind of rewriting — largely reduced, more than half a century after her death, to an episode in the literature of self-extinction. To my way of thinking, her portrayal there begins to drift toward the negative sense of “operatic”: exaggerated or melodramatic.

The emphasis on Woolf’s death may not be for everyone the most useful approach to understanding her, as a person or an artist. Julia Briggs makes the point in Virginia Woolf: An Inner Life (Harcourt, 2005):

Woolf’s life, like that of Sylvia Plath, is too often read in terms of her death, as if that was the most interesting or significant thing that happened to her. But like Septimus Warren Smith in Mrs. Dalloway, her death was the outcome of particular circumstances. Events seemed to conspire against her. . . . [Though she] like most people, could feel angry, paranoic, or depressed, she was for much of the time cheerful, lively, and creative — at once intensely private and absorbed in her imaginary worlds, and warmly sociable, amusing and amused.

Instead of attempting a more fully developed portrait of Woolf’s creative mind and mental state, circa 1923, while she was writing Mrs. Dalloway, Cunningham narrows the focus to the suicide theme, opening his novel with what he titles a “Prologue,” portraying her death in 1941. A prologue usually fills in what happened back before the central events (“What’s past is prologue”), rather than what happened eighteen years afterward. Passed over in silence in the novel The Hours are precisely those intervening years, when Woolf was living mostly in London, producing five more novels and a large number of essays, as well as working with Leonard to run their Hogarth Press, and thriving amid the company of major literary figures of the era. It’s important to remember that Mrs. Dalloway, far from representing some kind of endgame for Woolf, was in fact a breakthrough, opening up the years of her full maturity as an experimental novelist. It was not an end but a beginning.

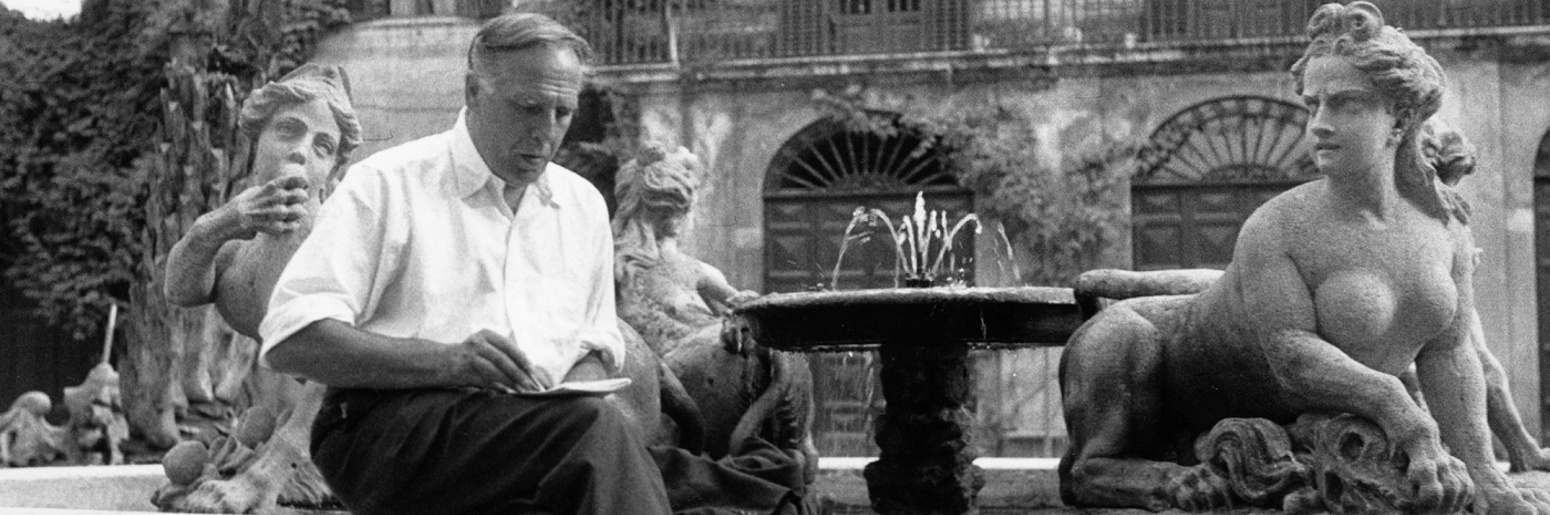

The photograph above was taken by Gisèle Freund in 1939, among her several portraits of Virginia and Leonard Woolf at their Bloomsbury house. It reminds us how much older Virginia Woolf was, how many years past her writing of Mrs. Dalloway, by the time World War II broke out, when its attendant terrors began to push her toward a recurrence of toxic depressive episodes. A year after this photograph was taken, while she and Leonard were residing in the country the Bloomsbury house was wrecked by a German bomb. (The fact that Woolf died at the age of fifty-nine would be ignored in the impossibly youthful casting of the actor who walks into the river in the film of Cunningham’s book.)

In the novel, Cunningham makes the suicide theme all-pervasive by adding two other characters, beyond Virginia Woolf, who also contemplate ending their lives, in the two other plotlines: Richard, the poet dying of AIDS, who is a contemporary variation on the shell-shock patient Septimus Warren Smith in Mrs. Dalloway; and Laura, who suffers silently amid the smothering normality of suburban America in 1949.

This multiplication of misery, attempting to expand the ramifications of Woolf’s own troubled situation, may perhaps be vulnerable to the charge of scattering the author’s resources. The Laura plotline especially, though touching, seems underdeveloped, lacking the psychological richness of Clarissa’s story, in the 1990s. Within the tripartite structure of the novel The Hours, despite its undeniable virtuosity, the other two plotlines reveal perhaps less than one might have hoped about the core issue of the overall enterprise: why, at one time, Woolf considered ending Mrs. Dalloway with the main character’s death. (Woolf went so far in preparing the ground in the novel as to point out that Clarissa Dalloway’s heart had been weakened by her illness during the influenza pandemic of 1918.)

A deeper exploration of just one, anchoring “case history” might have exerted greater centripetal force on The Hours enterprise, rather than letting it disperse its insights across three different time zones.

The scholar Edward Mendelson, in his book The Things That Matter: What Seven Classic Novels Have to Say About the Stages of Life (Pantheon, 2006), has looked deeper into the texture of Mrs. Dalloway as a work of fiction, discovering how the eponymous character could indeed have died, in a thematically convincing way, within her novel. He focuses on the “little room” into which she withdraws to be alone, after hearing from Dr. Bradshaw the distressing news of Septimus’s death. Mendelson finds in her “arrival” — that is, her return, at the very end of the book, from her sorrowful contemplation in the little room, to the party, her guests, and the “ecstasy” of her final appearance to Peter — a vestige of Woolf’s original thought that Clarissa herself might die:

The reason Virginia Woolf chooses this indirect way of describing Clarissa’s arrival seems to be that the book, in effect, remembers its author’s original intention (as described in her 1928 preface) to have Clarissa “kill herself, or perhaps merely to die at the end of the party.” In a ghostly invisible form, the original story is hidden within the published version as a parallel or shadow narrative that coincides with the story that takes center stage. In that invisible parallel narrative, Clarissa dies as she steps out of the little room. This shadow version of her death completes an action imagined earlier in the book, when Peter remembers Clarissa’s theory of the survival of the unseen part of ourselves.

This is the hard yet rewarding work that literary criticism does for us: developing new, richer insights into the imagination of a classic work through a scrupulous, sympathetic close reading of what the author actually wrote.

It’s perhaps a bit disappointing, therefore, given all the creative freedom allowed a literary artist, that The Hours, in its own quest to discover new insights, spends so much of its time ingeniously increasing the sheer number of the tragically long-suffering, those lingering on the lip of the volcano, from one (Septimus) in Woolf’s novel to three (Richard, Laura, Virginia) in the book Cunningham writes himself.

•

Nonetheless, in thus giving a more diverse scope to sorrow, Cunningham does display the fine sensitivity to music that marked Woolf’s choice of opera references in Mrs. Dalloway. Her allusions to the voluptuous music of self-abandonment, as encountered in Wagner and Strauss, posed a challenge to anyone trying to evoke a sound-world in a printed novel. Cunningham responded by proposing a different range of options.

For instance, as Clarissa Vaughan in The Hours pauses in front of a bookstore on Spring Street, looking to buy a present for a friend, she recollects a moment when the world was opened up to her by an unexpected experience with music:

Clarissa would have been three or four, in a house to which she would never return, about which she retains no recollection except this, utterly distinct, clearer than some things that happened yesterday: a branch tapping at a window as the sound of horns began; as if the tree, being unsettled by wind, had somehow caused the music. It seems that at that moment she began to inhabit the world; to understand the promises implied by an order larger than human happiness, though it contained human happiness along with every other emotion. The branch and the music matter more to her than do all the books in the store window.

An epiphany like this one, when “the sound of horns” reveals “an order larger than human happiness,” provides hints that (thinking ahead) a scriptwriter and film composer might want to follow up.

Just as suggestive, when Clarissa walks on to Washington Square, Cunningham likely alludes to the beggar woman singing the cryptic phonemes “ee um fah um so / foo swee too eem oo” in Regent’s Park in the novel Mrs. Dalloway:

Ahead, under the Arch, an old woman in a dark, neatly tailored dress appears to be singing, stationed precisely between the twin statues of George Washington, as warrior and politician, both faces destroyed by weather. . . . Under the cement and grass of the park (she has crossed into the park now, where the old woman throws back her head and sings) lay the bones of those buried in the potter’s field that was simply paved over, a hundred years ago, to make Washington Square. Clarissa walks over the bodies of the dead as men whisper offers of drugs (not to her) and three black girls whiz past on roller skates and the old woman sings, tunelessly, iiiiiii. . . . the bleat of car horns and the strum of guitars (that ragged group over there, three boys and a girl, could they possibly be playing “Eight Miles High”?); leaves shimmering on the trees; a spotted dog chasing pigeons and a passing radio playing “Always love you” as the woman in the dark dress stands under the arch singing iiiii.

Again, this welter of auditory stimuli provides a number of hints that a film composer could capitalize upon: not only the reference to the now well-known Wagnerian allusion, but a diversity of other sonic elements and musical styles.

These examples of Cunningham’s musicality, from Clarissa’s early childhood to her present moment, evidence an “operatic” manner in the more positive sense: lyrically expressive.

As it turned out, however, the hermetic sound-world of The Hours film as actually produced would not accommodate the likes of the Byrds’ “Eight Miles High” or Whitney Houston’s “I Will Always Love You.”

Philip Glass and The Hours on Film

Biographer Hermione Lee has written tellingly about portrayals of the novelist, in a collection of essays called Virginia Woolf’s Nose: Essays on Biography (Princeton, 2005). There she finds the film version of The Hours limited by its single-minded focus on the writer’s death, reinforced by its score:

At the beginning of the film The Hours . . . we hear in voiceover the words of Virginia Woolf’s suicide note to her husband, Leonard, and we see Nicole Kidman as Woolf, looking young and fierce, writing the note, leaving her country house (on a beautiful summer day), walking determinedly, in a tweed coat, down the garden path and towards the river-bank, and slowly entering, until she is fully immersed, the green, sun-and-shade-dappled waters of a gently flowing river, to the accompaniment of birds calling and a pulsating, emotional score by Philip Glass. Since the film begins with this romanticised version of the suicide of Virginia Woolf, it sets up a lifestory which is moving inexorably towards that death.

This romanticized film death does, of course, suggest the negative side of the “operatic”: exaggerated or melodramatic.

About David Hare’s script, Lee further points out:

How should we treat death? David Hare — perhaps too consolingly — imagines the voice of Virginia Woolf telling us, as she leaves us, that she has mastered this question, and understands what to do: “to look life in the face and to know it for what it is; to love it for what it is, and then to put it away.”

In the film, we see Leonard discover, open, and read the suicide note Virginia left for him. But the lines heard here, about looking life in the face, are not from her note. The quoted lines — the most renowned passage in the film of The Hours, and since then routinely attributed to the historical Virginia Woolf in dozens of memes and the like — were not written by Woolf at all, nor were they written by Michael Cunningham. They were apparently composed by David Hare in preparing the screenplay. The script is thus in this respect at a double remove from actuality: the historical Woolf as reimagined by Cunningham, and Cunningham as reimagined by Hare.

In moving from page to screen, the characterization of Woolf in The Hours enterprise becomes even more narrowly focused on her terrible struggles with anxiety and depression, leaving out almost everything else about her life. As Lee further writes of the film: “I wish something of Woolf’s gleeful comedy, her hooting laughter, her allure, and her excited responses to people and gossip, had been caught.”

But instead of portraying Woolf’s often energetic, intellectually dynamic life, it’s remarkable how the text of Hare’s published screenplay blatantly romanticizes her dead body:

At once the image of Virginia Woolf’s body, face down, swirling fantastically like a catherine wheel, back on the surface of the water and carried along by the current. Her hair is unloosed, her coat has billowed out. Her body swirls, moving fast downstream, wildly festooned like Ophelia . . .

With these words, the screenwriter veers dangerously close to the mid-Victorian sentimentality of painter John Everett Millais, and his voyeuristic, aestheticized view of Ophelia’s ugly death by drowning in Hamlet.

•

Abetting the emphasis on predetermined ends, the film score’s metrically precise music, with its insistently rhythmic forward motion, propels the characters — across all three plotlines — toward their fates. (Listen to a clip from Philip Glass’s score.)

In interviews, Philip Glass has spoken about how he decided to apply a single, consistent style of scoring to all three stories, in order to hold the disparate, shifting timeframes together. A more period-minded kind of musical intelligence might perhaps have wanted one style for the Virginia Woolf/Nicole Kidman scenes, set in 1923; a different style for the Laura Brown/Julianne Moore scenes, in 1949; and yet another for the Clarissa Vaughan/Meryl Streep scenes set in the late 1990s, including the death of Richard Brown/Ed Harris. But Glass’s instincts were right, for the film. His score goes a long way toward achieving the unity of cumulative effect that the constant, rapid crosscutting between the three timeframes — far more fluid (or disjointed?) than Cunningham’s tidy chapters — can seem to undermine.

Glass’s characteristic manner is so unmistakable, and so adept at monitoring the varying tension levels of the storylines, that he seems, at least on this occasion, like a postmodern heir of Bernard Herrmann (1911-1975), who most famously scored the portrait of passionate, self-destructive fixation in Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo, balancing a steady pulse of arpeggios with a wide variety of inventive rhythms and shifting instrumental colors. (Listen to a clip from the Vertigo soundtrack.)

More than anyone else, Glass is responsible for those moments when the film of The Hours rises to the “operatic” — in the positive sense of lyrically expressive.

•

A song by Richard Strauss makes a brief but memorable appearance in The Hours.

As a kind of counterpoint to Glass’s spare, disciplined writing, the film’s soundtrack includes one episode of the voluptuously Late Romantic. Clarissa’s old friend Louis comes to visit her unexpectedly after a long absence, as she’s preparing for the party. After her upsetting earlier visit to check up on Richard, she’s trying to calm herself by listening to a recording of Strauss’s “Beim Schlafengehen” (“On Going to Sleep”) from Four Last Songs. (Watch a clip from this scene.)

The song title’s reference to going to sleep must be on Clarissa’s mind, as Richard is in a final decline, and so she immerses herself in opulent music (here majestically sung by Jessye Norman) to, so to speak, take the edge off.

In some ways, this is a basic character trap in the film of The Hours: trying to deny thoughts of death by escaping into sheer aesthetic pleasure, just as the troubled Laura, in 1949, encloses herself in a hotel room of her own to read Mrs. Dalloway in peace and solitude.

But to attempt this escape is, in the idiom of the screenplay, to fail “to look life in the face and to know it for what it is.” Woolf the character looks life in the face and decides to die, while Laura decides to live.

In an opera, as we shall see, the two of them could have sung through their opposite decisions in a duet. Or in a trio with Clarissa.

The Hours as an Opera

Anticipating the official debut at the Met of the fully staged opera, the Philadelphia Orchestra presented The Hours in a concert version eight months earlier.

Peter Burwasser’s review of the concert performances in March 2022 captured the complexity of Kevin Puts’s musical approach and perhaps some of the difficulties he faced:

There is a rhythmic propulsiveness in the manner of John Adams and Philip Glass, as well as lilting melodic patterns that recall Samuel Barber. These identify Puts as an American artist, but surely his overwhelming musical influence is the operatic output of Richard Strauss, particularly in Puts’s ability to fluidly pivot from cacophonous, richly textured outbursts to tender, emotionally introspective vignettes.

In light of the prior history of The Hours, some of Puts’s influences may have threatened to become something more like baggage, since he draws inspiration from composers we’ve already seen in a Woolfian context. His “rhythmic propulsiveness in the manner of . . . Philip Glass” could be problematic, since Glass had already created an award-winning score for the film of The Hours, and creative artists want to avoid any sense of imitation. So too with Richard Strauss, who in the film of The Hours provided a soaring Romantic moment: conspicuously, the only non-Glass music on the soundtrack. It cannot have been easy for Puts to contemplate the Woolf-related works of two of his composer role models.

But note, first off, that in Puts’s score — in just the opposite manner from Glass’s — each of the three plotlines has, to some extent, its own style, as conductor Yannick Nézet-Séguin made clear to the players in the first orchestral rehearsal (watch a clip), speaking about “twenties music” in the Virginia Woolf scenes. The midcentury American easy-listening music briefly heard in the Laura Brown/Kelli O’Hara scenes (referencing a style popular after the Big Band era, but before anyone dreamed of rock and roll) drifts out over the audience like a collective memory. The Clarissa Vaughan/Renée Fleming scenes, in the late 1990s, include high-culture references, among them, appropriately enough, vocal works by Mozart and Strauss.

The three period styles match the tripartite division of the Met’s stage in the production design, aptly described in the New York Times’ review of the debut: “In Tom Pye’s scenic design, the three stories are presented on realistic islands that float around a bare stage.”

•

In some unexpected ways, certain individual features of the prior material find a new place in the opera.

For instance, the puzzlingly oblique role of the “Man Under the Arch” (hauntingly sung by countertenor John Holiday) in the opera recalls the phonemic song of the beggar woman in Regent’s Park in Mrs. Dalloway, where her incomprehensible, unheeded commentary, like Erda’s, cast a shadow across the plot.

The Met’s program notes give a clue to another specific adaptive issue faced by composer and librettist. The notes describe a scene set in the Woolfs’ suburban Richmond house this way:

Virginia asks her cook, Nelly, whether she believes that a young woman could start the day joyfully and then decide to kill herself. This leads Virginia into a fantasy foreshadowing the way she’ll eventually end her own life.

Recalling the icy, antagonistic relationship between Woolf and her cook as depicted in the novel and film, her seeking Nelly’s feedback on a possible plot point in writing Mrs. Dalloway seems strangely out of character, especially considering their established servant/master roles.

However, Nelly’s raison d’être is simply to give Woolf an occasional conversation partner. Nelly (sung by Eve Gigliotti) and her brief replies are pressed into service to address a libretto-writing problem: at some basic level, modernist fiction’s innovative stream-of-consciousness technique may be unsuited to spoken (or sung) theatrical presentation, because that consciousness has to actually talk to someone sometimes, onstage, to create workable dialogue, unless the audience is to sit through long stretches of uninterrupted, elusive, meandering interior monologue. That’s a lesson playwright Eugene O’Neill learned in the 1920s, in his struggle to strike a balance in his Strange Interlude (1926-28).

Other benefits derive from the device of the Nelly scene. Her usefulness as a prompt to Virginia’s thoughts (SPOILER ALERT) makes possible the masterstroke the opera offers us, as opposed to the novel and film. That is, this time we don’t have to watch Virginia Woolf commit suicide. Kudos to Puts and Pierce. For once, in an opera, a woman doesn’t die at the end.

The portrayal of Woolf’s death by drowning in the River Ouse, as shown (twice) in the film, has always seemed gratuitous to some of us — “operatic,” in the malign sense of “melodramatic” — since no one can ever know her demeanor and final thoughts as she went into the water in 1941, at the age of fifty-nine: not even whether she might conceivably have changed her mind when it was too late, or struggled to resist the current. Some basic facts are of course known, such as the dead-weight stones found in her coat pocket, or the wording of her suicide note(s). But whatever was supposedly happening inside her mind and body at the very end has essentially been made up, first by Cunningham and then by Hare.

In the opera, in contrast, in a moment of foreshadowing prompted by Nelly, the relatively abstract presentation of the River Ouse as a mass of moving dancers’ bodies, with Woolf off to the side at a safe remove, allows us to contemplate the author’s eventual end, eighteen years later, without feeling like gaping voyeurs.

•

Despite the extraordinary dancing in the vision of the river, as choreographed by Annie-B Parson, it must be acknowledged that some may find the opera’s larger scaled episodes at times less successful.

The elaborately overproduced flower scene in particular can look and feel a bit too much like a flash crowd. (Watch a clip of the flower shop scene.) The novel Mrs. Dalloway’s opening sentence — “Mrs. Dalloway said she would buy the flowers herself” — while efficiently serving its author’s purpose of setting the story in motion, cannot easily bear the enormous weight of significance, and sheer repetition, imposed on it at the outset of the opera. The line is not, after all, poignantly wise, in the manner of Tolstoy’s first sentence in Anna Karenina (“All happy families are alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way”), which boldly announces the ensuing novel’s theme. Nevertheless, the commotion at the florist shop in The Hours keeps ringing the changes on that flower-buying sentence — with awkward punning on the words “buy” versus “by” (“buy the flowers . . . by herself”) — as if its ramifications were inexhaustible. Yet the enormous Met stage needs to be filled, somehow, and an ambitious song-and-dance number accomplishes that.

Compare that pop-up extravaganza to the economical modesty of the flowers as seen with Meryl Streep (Clarissa Vaughan) in the film version.

Of course, this is a somber opera, and it could use a little lift like the florist shop once in a while. In addition, in a 1949 scene we see little Richie and his straight-arrow father, Dan, gleefully playing silly word games at the breakfast table, as when Richie says his bowl of cereal is getting “swampy.” The titters in the Met audience at that episode of midcentury sitcom father-and-son banter suggest a production team unafraid to trigger a family-friendly flashback to Leave It to Beaver.

But even at breakfast there’s a crowd, as the dancers enact a parade of home appliances through the kitchen.

Oftentimes the overcrowded, hyperactive staging of private lives can make even a strong scene ring slightly false. Even when Virginia Woolf (Joyce DiDonato) is seen alone, lost in thought at her writing desk, her solitude is shattered by the arrival of prop-changing stagehand elves.

•

After seeing The Hours live in the house, I watched it again in the “Met in HD” video transmission, where the greater readability of the subtitles and, more important, the availability of carefully composed closeup shots and camera movements made what was going on both more comprehensible and more affecting. As has often been pointed out in recent years, the Met’s productions these days seem largely designed and lit to exploit the shifting viewpoint of the TV camera, with the experience of the audience member sitting immobile in the house almost an afterthought. The audience at the bricks-and-mortar Metropolitan Opera House is there to applaud, laugh, and cry, and thereby validate the performance for remote video viewers. Perhaps someday, when HD transmissions have become the Met’s preeminent way of communicating with its viewers, each broadcast will be accompanied by the preamble that used to precede each episode of the 1980s TV series Cheers: “Filmed before a live studio audience.”

In HD, the vast theatrical space looming over the death of Richard, the visionary poet, is cut down to only his little apartment, contributing to its pathos, despite the Met’s lofty proscenium soaring overhead. The camera’s closeups hide the distracting gigantism of the stage’s surround. (Watch a clip of this scene.)

Indeed, at the Met and in HD, the two scenes with Richard (sung with dignity and restraint by Kyle Ketelsen) remained the most moving in the opera. It may be instructive to compare them to the death scene of Richard’s model and source: the shell-shocked veteran Septimus Warren Smith in Mrs. Dalloway. A chamber opera version of Mrs. Dalloway was produced at Lyric Opera Cleveland in 1993, with music by the prolific American composer Libby Larsen and libretto by Bonnie Grice. In it, the long scene of Rezia and Septimus at home culminates in his death — as he jumps from the window, fleeing the threat of forced psychiatric incarceration. (Watch a clip from Lyric Opera Cleveland.)

Part of the emotional intensity of an operatic scene like this comes from its intimacy, which the Met production of The Hours somehow manages to achieve from time to time, especially onscreen, when we are allowed to forget a problematic venue accommodating 3,850 audience members, many of them very far away from the stage.

Nonetheless, despite the scale of the house, the Met’s acoustics help draw the audience in. Even in such a large auditorium, the orchestra can fill the aural space with a huge wave of sound and then, if desired, pull back for the whisper-level exchanges. One of the great moments in the score is the massive symphonic outpouring immediately after Richard’s death. A powerful elegy, gloriously played by the Met orchestra and sung by the Met chorus, it offers a rush of pent-up emotion after the most wrenching scene in the opera. (Listen to an audio clip from the Met radio broadcast.)

•

In Mrs. Dalloway, Woolf portrays one of her ruminating characters, Peter Walsh, as he happens by chance to observe the ambulance that carries Septimus’s body away. Peter’s thoughts also take the form of an elegy:

And yet, thought Peter Walsh, as the ambulance turned the corner, though the light high bell could be heard down the next street and still farther as it crossed the Tottenham Court Road, chiming constantly . . . yes; really it took one’s breath away, these moments; there coming to him by the pillar-box opposite the British Museum one of them, a moment, in which things came together; this ambulance; and life and death. It was as if he were sucked up to some very high roof by that rush of emotion . . .

Thoughts of “some very high roof” in his elegy for an unknown stranger who leaped from a building form one of many examples of a kind of hidden mental transfer between the discrete, multiple consciousnesses — here between Septimus and Peter — at work in Mrs. Dalloway, and which becomes a model method of the opera.

•

Puts returns to his most intimate style in the final scene. (Watch a clip.) Some press reviewers had snarky things to say about the final trio with the three stars. We know that Puts admires Strauss, and for that very reason it could have seemed unwise to reference, however remotely, the final trio of Der Rosenkavalier, in which Renée Fleming used to sing the Marschallin and Joyce DiDonato has sung Octavian. But to complain about the existence of The Hours trio is to ignore the eerie, drama-defining fact that it gives Virginia Woolf a chance to hold hands with a version of her creation, Clarissa.

Which is to say: The Hours trio does succeed in drawing out the therapeutic effect embedded in the way Woolf wrote Mrs. Dalloway in the first place.

Angus Fletcher, who holds dual degrees in neuroscience and literature, has written about her use of stream-of-consciousness, in his Wonderworks: Literary Invention and the Science of Stories (Simon & Schuster, 2021):

Woolf’s style provides the same therapeutic effect. As it guides us through the consciousnesses of character after character after character, it gradually attunes our brain to a greater consciousness: the third-person perspective of the novel itself. That perspective weaves us in and out of the minds of Clarissa, Scrope, Septimus, and all the rest, enabling us to simultaneously experience inside feelings and outside distance. The resulting blend of emotional perception and cognitive separation mimics the modern psychiatric treatment for heightened cognitive reactivity. Filling our consciousness with mental flow, yet reducing the neural activity of our cortical midline structures and insular cortex, it allows us to experience emotional torrents while remaining free of their undertow. In this therapeutic state, we can be conscious of Clarissa’s “shock of delight” and Septimus’s desperate suicidal thoughts without being shocked or desperate ourselves. We can know the river’s deepest currents while feeling calm upon the shore.

At its best, when The Hours weaves the voices of Clarissa, Virginia, and Laura into a trio — manifesting on the opera stage this liberating blending of their different emotional and cognitive states — the music gives us access to what Fletcher calls “a greater consciousness.”

In the modern age, that may be as close as we get to catharsis.

(December 2022)