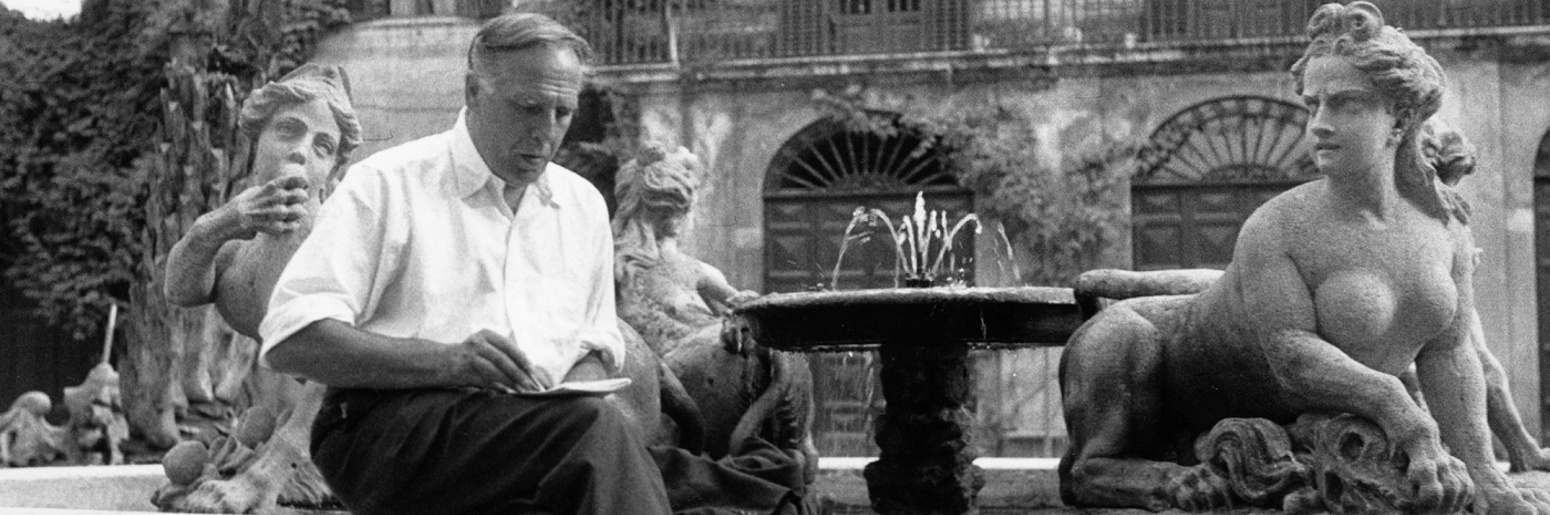

James Leggio

Johann Sebastian Bach’s St. John Passion begins with one of the composer’s most compelling choruses. (See a video clip, with Jos van Veldhoven conducting, or a complete German/English libretto.)

Lord, our ruler, whose fame

In every land is glorious!

Show us, through your passion,

That you, the true Son of God,

Through all time,

Even in the greatest humiliation,

Have become transfigured!

This chorus is not the towering, majestic opening that might have been expected, especially by listeners familiar with the St. Matthew Passion. Here, instead, with “the greatest humiliation” lying ahead, the orchestra when first heard sounds unsettled: the anxiously repeated string phrases; the tread of the bass notes, suggesting a forced march; the sour wailing of the oboes; and then the intensely articulated vocal runs in the choir convey something akin to anger. The energy of nervous conflict remains palpable to an audience two hundred and seventy years after the composer’s death.

Yet how we hear this music is in some ways fundamentally different from how audiences heard it during Bach’s lifetime. Certainly, through the work of many musicologists and conductors since the 1970s the instruments we hear today in this repertoire are largely “period,” and our choirs are generally closer in size to the twelve singers Bach may have employed. But still, how we hear Bach’s church music is quite different — different in acoustical ambience, and in the positioning of musicians within the performance space — from what congregants heard in the first venues: Leipzig’s St. Nicholas Church in 1724 and St. Thomas Church in 1725.

In a reconstructive study of the acoustics of these two churches, Thomas Braatz notes that despite the differences between them, in both “the sound issued from a location high above the ground floor,” and he quotes the German musicologist Arnold Schering to the effect that in both churches, “The organ and choir lofts did not extend visibly into the nave of the church, but rather created a realm unto itself separate from the congregation.”

In this separate realm up above, and hidden away at the rear of the church, the soundtrack of biblical scenes was played out by musicians who, for the most part, could not be seen by the general public. The creation of a floating musical domain above the heads of the faithful appears to have been especially effective in Bach’s home-base church of St. Thomas, where the acoustics produced a somewhat more finely dispersed sense of hall resonance that Schering called “dematerialized” (entmaterialisiert). Though both churches have since been drastically altered, the word dematerialized captures the characteristic ambient quality that Bach expected from his home church. The music wafted down from an intangible world on high, promoting the spirituality of the unseen. It is from the airy realm consecrated to music, above, that we below are to hear the Passions, along with Bach’s other religious works.

Nowadays, of course, the Passions are most often performed in the very different ambience of concert halls, with the musicians on a stage in front of the audience. And even when performed today in a church, the Passions are generally treated as special public events that, quite understandably, move the musicians out of the elevated, largely unseen choir loft in the rear, and down to the main floor — in front of the altar, displacing a service rather than serving it. The church turns into a glorified playhouse. Instead of invisible holy events, the Passions become material plays that need to be “staged” somehow.

The Problem of Staging the Trial Scene

Under these modern performing conditions, producers and conductors often feel obliged to justify, or at least explain, how they’re staging these front-and-center Passions, whether in church or concert hall. For example, the website of Apollo’s Fire, the Cleveland Baroque Orchestra, carries this advisory on its performance of the St. John Passion, conducted by Jeannette Sorrell:

THE CONCEPT: Ms. Sorrell’s vision for the production sought to bring immediacy and clarity to Bach’s dramatic structure through several means. The “action” (storytelling) scenes take place on a specially lit platform in the center of the orchestra. All of the characters — Jesus, Pilate, Peter, etc. — perform their roles from memory, physically confronting each other on the platform. The “reflective” arias, in which Bach takes us outside of the story to contemplate what just transpired, are performed at the front of the stage, away from the drama platform. In the extended “mob” scene of the Trial Before Pilate and up through the climactic Condemnation of Jesus, half of the chorus is placed amongst the audience [as seen in this video clip], shouting at Pilate from the aisles.

The dynamic between Pilate and the “mob” is so much at the center of the “action” that the producers include a video interview with Jeffrey Strauss, the singer playing Pilate, talking about how his problematic character presents his dilemma to the audience.

It’s significant that here and in other productions, the treatment of the so-called “mob” scene is singled out for special attention. In the DVD liner notes to the performance of the St. John Passion conducted by Peter Dijkstra we read:

. . . by far the longest part is devoted to the trial between Pilate, Jesus, and the Jews. This places the human tragedy of Pilate at centre stage: he is torn between the incarcerated Jesus and the raging mob out in the street, and his fear of the crowd finally makes him decide against his own conscience. The arrangement of choir and orchestra in our performance also contributes toward the presentation of this conflict: the orchestra is seated between the two-section choir, and the singer of Pilate can physically feel the power of the raging mob, “threatening him musically” from two sides [as seen in this video clip]. He has to turn to face Jesus, however.

Like many other performance groups, the producers of these two stagings of the St. John Passion focus on one difficult issue: how to direct the scenes featuring “the Jews . . . the raging mob out in the street” without evidencing anti-Semitism, or perhaps more accurately, anti-Judaism. How do you maintain a focus on the intended message about the tragic grandeur of Jesus’ death, while also acknowledging the ferocity of the “mob” scenes in the trial as staged by John himself in composing his gospel?

The Trial Drama as a Theological Invention

It has been argued that in the gospel attributed to St. John the Evangelist the entire trial scene is likely an authorial invention.

The biblical scholar John Dominic Crossan declares that “the Trial is, in my best judgment, based entirely on prophecy historicized rather than history remembered. It is not just the content of the trial(s) but the very fact of the trial(s) that I consider to be unhistorical” (Who Killed Jesus? Exposing the Roots of Anti-Semitism in the Gospel Story of the Death of Jesus, 2009, p.117).

The convening of a trial is historically highly unlikely because no such proceeding was in any way necessary, or even plausible, according to how Jesus’ arrest and execution were set in motion. In Crossan’s view, and that of Géza Vermès, “Jesus’ downfall was precipitated by the fracas he caused in the sanctuary at Passover,” the episode in John about the money-changers at the Temple (Vermès, Introduction to Partings: How Judaism and Christianity Became Two, 2013, p.25). As Crossan vividly continues the story, “. . . and the soldiers moved in immediately to arrest him” (Jesus: A Revolutionary Biography, 1994, p.150).

Here is how John (2:13-19) recounts the dramatic event that would cost Jesus his life:

The Passover of the Jews was at hand, and Jesus went up to Jerusalem. In the temple he found those who were selling oxen and sheep and pigeons, and the money-changers sitting there. And making a whip of cords, he drove them all out of the temple, with the sheep and oxen. And he poured out the coins of the money-changers and overturned their tables. And he told those who sold the pigeons, “Take these things away; do not make my Father’s house a den of thieves. . . . Destroy this temple, and in three days I will raise it up.”

This is Jesus’ most aggressive act in any of the gospels. Disrupting the Temple’s unique function as the place of sacrifice to God and, in addition, alluding to its destruction, with breathtaking recklessness he mounts an offensive that seems to invite political punishment. Moreover, in a rash phrase that openly flirts with blasphemy, he speaks of the Temple not as “our” Father’s house but rather as “my Father’s house.”

Attacking the legitimacy of the priestly regime, as well as challenging civil law and order, and particularly during the politically volatile time of the Passover, would have been more than enough to merit summary execution, especially in what was essentially a Roman police state. Jesus had brazenly committed a grave crime against both the imperial and local authorities, and in public, for all to see. With nothing in dispute to adjudicate, there was simply no need for a trial.

But it can be maintained that it was John who needed a trial, and a detailed one, for his own purposes. For him, a fictionalized story about a trial was an opportunity for doctrinal exposition: to argue out, in dialogue form, the nature of Christ’s kingship, for the benefit of a presiding Roman ruler.

Chronology is important here. Jesus had died in 33 CE. By the era when John’s gospel was being written, around 100 CE, a lot had changed. A number of the early church’s leaders were turning away from seeking Jewish converts in what seemed to them a hostile, recalcitrant Jerusalem: in 44 CE, Herod Agrippa I had put to death the apostle James and arrested Peter (Acts 12:1-3); and in 62 CE, the head of the early Christian congregation in Jerusalem, “James the brother of Jesus,” was stoned to death, according to the ancient historian Josephus (Jewish Antiquities 20.9).

At the same time, some of the early leaders were turning toward Rome, which looked more promising for gaining (gentile) converts. Especially after the destruction of the Temple of Jerusalem, in 70 CE, Rome became the focus of what the early church may have thought of as its theological manifest destiny.

John’s account of the trial scene, composed at the end of the first century, is all about Christ being sympathetically defended by a legal representative of Rome — an ideal storyline for establishing legitimacy in the empire and cultivating Roman converts.

•

The biblical scholar and John gospel specialist Raymond E. Brown frequently pointed out in his book The Death of the Messiah (1994) and in his edition The Gospel According to John (2 vols., 1966, 1970) that the trial before Pilate, as written by the John author(s), is not to be confused with the transcript of a legal proceeding. It has little to do with either Roman law or Jewish custom.

Instead of a true trial, almost seventy years after Jesus’ death John creates a densely packed play, a stage drama, in seven scenes, that is more complex and detailed than any trial account in the other canonical gospels. As Brown writes in his edition of John’s gospel (p.858), “There are two stage settings: the outside court of the praetorium [judgment hall] where ‘the Jews’ are gathered; [and] the inside room of the praetorium where Jesus is held prisoner. Pilate goes back and forth from one to the other in seven carefully balanced episodes.”

The conductor John Eliot Gardiner concurs about the histrionic nature of the setup: “The sheer theatrical dynamism is here unprecedented. Not even the lake-storm in his cantata BWV 81, Jesus schläft, can match this for sustained dramatic momentum. Crucial to its effectiveness, again, is the physical deployment on an imaginary stage set: Christ as prisoner, immobile (perhaps immobilised) in the judgement hall, the crowd holding back in the outer court, ‘lest they should be defiled,’ Pontius Pilate the go-between” (Bach: Music in the Castle of Heaven, 2013, pp.368-9)

The structure of scenes taking place on this “imaginary stage set” is so schematic and so symmetrical — so much a creative-writing artifice — that Brown was able to produce the verse-by-verse plot diagram of the proceedings shown below. The arrows indicate the direction of the action. Equal signs mark the similarity of the scenes placed symmetrically on either side. The symmetry manifests itself in how Scene 1 is mirrored in Scene 7, both being about a demand for death; Scene 2 is mirrored in Scene 6, both showing Pilate and Jesus conversing in private; and Scene 3 is mirrored in Scene 5, for in both, Pilate finds Jesus not guilty.

Rather than a mere abstraction, Brown’s diagram gets at the intrinsic structure of the St. John Passion. As Eric Chafe notes: “John’s gospel is famous for what have been called its ‘typical chiastic patterns,’ and of these patterns the trial is the best known and most conspicuous; that is, episode one resembles seven, episodes two and six and three and five, are similar, while John shifted the scourging to place it at the center of the trial (episode four), the only scene that involves the Kriegsknechte rather than Pilate or the crowd” (Tonal Allegory in the Vocal Music of J.S. Bach, 1991, p.309).

As the diagram makes clear, Pilate’s repeatedly going back and forth between the outdoor courtyard (where the high priests stand) and the interior of the judgment hall (where the prefect interrogates the defendant) is a theatrical way of portraying, or “staging,” Pilate’s uncertain, vacillating view of the action unfolding before him. A historical Roman personage well known for his brutality is here turned into a sensitive, inquisitive figure of Hamlet-like indecision.

His exchanges with Jesus are the most memorable moments of the play. As presiding judge, he asks the prisoner a series of loaded questions, perhaps a risky move given this peasant preacher’s reputation for offering oracular, and therefore irrefutable, answers under hostile interrogation. To cite a famous example, recall Jesus’ reply during his ministry to an entrapment question from the Pharisees, which they had set up as a yes-or-no choice: “Rabbi, is it lawful to pay taxes to Caesar?” It’s the kind of thing present-day lawyers crudely call a have-you-stopped-beating-your-wife question; whether you say yes or no, you lose. In this trap about taxes, if you say yes, you’re siding with the oppressors of your own people; and if you say no, you’re liable to be accused of inciting rebellion. But Jesus, pointing out the emperor’s likeness stamped on a Roman coin, finds a different way — resourcefully asserting a distinction between church and state: “Render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and unto God the things that are God’s” (Matthew 22:15-22). Thrown a curveball, he hits it out of the park.

Now too, bringing all his stage presence to the role of defendant, Jesus responds with incisive, memorable statements that become articles of faith to the church. Indeed, he was by now in the evangelists’ accounts such an experienced debater that at times he puts the prefect on trial and interrogates him. Therein lies much of the drama of this carefully wrought play.

Who would have expected John to turn out to be one of the great, if unacknowledged, playwrights of antiquity? Yet performances of the St. John Passion demonstrate as much.

In the pages that remain, I’ll highlight how the calculated histrionic structure of a “Trial Before Pilate” drama, in seven scenes, plays out as an aesthetic artifice. To put the drama in context, we’ll want to crisscross back and forth from John’s gospel itself (c.100 CE) to Martin Luther’s sermons on chapters 18 and 19 of John (1528/29-1557), to Bach’s composition of the St. John Passion (1724), and finally to modern interpreters of this historical evolution.

•

Following the interruption for the Good Friday vespers sermon, the St. John Passion resumes with Part 2, containing the trial scene. Again, as with the opening chorus of Part 1, the audience is reminded of redemptive kingship, which “makes us blessed”:

ST. JOHN PASSION, Part 2

Chorale

Christ, who makes us blessed,

committed no evil deed;

for us he was taken in the night

like a thief,

led before godless people

and falsely accused,

scorned, shamed, and spat upon,

as the Scripture says.

SCENE 1 (OUTSIDE): DEMAND FOR DEATH

(See a video clip, with Roger Norrington conducting.)

Evangelist: Then they led Jesus before Caiaphas in front of the judgment hall, and it was early. And they did not go into the judgment hall, so that they would not become unclean; rather that they could partake of the Passover. Then Pilate came outside to them and said:

Pilate: What charge do you bring against this man?

Evangelist: They answered and said to him:

Chorus: If this man were not an evil-doer, we wouldn’t have turned him over to you.

Evangelist: Then Pilate said to them:

Pilate: Then take him away and judge him after your law!

Evangelist: Then the Jews said to him:

Chorus: We may not put anyone to death.

Evangelist: So that the word of Jesus might be fulfilled, which he spoke, where he indicated what death he would die. . . .

COMMENTARY:

In his sermons on John’s gospel, Martin Luther speaks of this episode in harsh terms: “When the Jews hear Pilate ask what sort of accusation they are bringing against Jesus, their conscience wavers, since they do not dare to come out into the open with it.” As he said a few sentences earlier, “The same thing is happening today to the enemies and persecutors of the Gospel. The pope with his godless bishops and prelates knows full well that he is committing an injustice, and yet they charge insolently ahead” (Luther’s Works, vol. 69, 2009, pp.204-5).

Apparently, the worst insult Luther can hurl at the high priest Caiaphas and his entourage is to say that they’re acting like papists! It’s a tactic he uses more than once, and interestingly, it suggests that Luther sees himself as an analogue of Christ, persecuted and falsely accused by a “godless” supreme ecclesiastical authority.

Already at this early point Bach’s drama is falling into a generalized, monolithic treatment of Judaism. For although Caiaphas is identified in the first line as the putative prosecutor of the case, the principal in the procession to Pilate, he never in the entire St. John Passion has any lines as a solo-voice character, unlike Peter or even Annas’ servant. That’s not Bach’s fault, however. Although Caiaphas had in fact in the priestly council laid out numerous charges requiring Jesus’ death, that was back in earlier chapters of John’s gospel, before the trial was convened. His earlier accusations are now — in the chapters devoted to the trial — largely imputed generically to “the Jews,” represented mostly as an undifferentiated group.

As Sonya Shetty Cronin writes, discussing the Septuagint’s ancient Greek term hoi Ioudaioi: “Brown simplifies much of this discussion regarding the anti-Judaism in the Gospel of John by stating that it rests chiefly on how John refers to ‘the Jews.’ The defining historical question regarding anti-Judaism in the Gospel of John is ‘Who are οἱ Ἰουδαϊσμός?’ Are they Synagogue members, during the time of the author, Synagogue leaders during the time of the author, Judeans (regionally), or other possible subgroups of Jews active in the first century?” (Raymond Brown, “The Jews,” and the Gospel of John: From Apologia to Apology, 2015, p.6). Further possibilities are raised as well.

James H. Charlesworth also writes about the crucial language problem: “The foreshadowing of anti-Judaism can be seen in the Gospel of John, in which ‘the Jews’ are portrayed as Jesus’ opponents. Unfortunately, too many miss the point that sometimes the Greek Ioudaioi means some ‘Judean’ leaders” (“Did They Ever Part?,” his contribution to the volume Partings, p.289). Similarly, as James D.G. Dunn writes: “. . . the shift from a purely ethno-geographic term [‘Judean’] to one of religious significance [‘Jew’] is first evident in Macc. 6.6 and 9.17, where for the first time Ioudaios can be translated as ‘Jew’; and in Greco-Roman writers, the first use of Ioudaios as a religious term appears at the end of the first century CE” (Jesus, Paul, and the Gospels, 2011, p.122, commenting on Shaye J.D. Cohen’s The Beginnings of Jewishness, 1999).

Thus, the John author himself, living at the end of the first century CE, was writing at a time when the accepted Greek term, Ioudaioi, still meant something like “Judeans,” i.e., those living within the geopolitical boundaries of Judea. But the word was also moving in the direction of meaning “Jews,” implying the religious beliefs of the people. And that ambiguity would prove problematic, to say the least.

Whether he meant “Judean leaders” or “Jews,” it was John’s creative choice as a dialogue writer to set up the accusations as uniform crowd-speak, rather than, say, having Caiaphas step forward to make the case before Pilate in his own solo voice. And retaining, in German, the much-vexed identification of the collective “die Juden” was, of course, inevitable for Bach; no church-employed Lutheran composer was going to alter Martin Luther’s translation. Given only this group-speech to work with, perhaps it’s to be expected that a composer might seize upon the aggregate “die Juden” as an opportunity for strong choral writing — too strong, for most of us.

Specifically of the choruses, Michael Marissen writes: “I wonder if the St. John Passion readily lends itself to anti-Jewish construal because of the highly expert musical settings of the biblical choruses. No matter what the St. John Passion’s arias, chorales, and framing choruses have to offer as commentary, what may still ring too easily in people’s ears today are the terrifying repetitions of the biblical text’s ‘Crucify, crucify!’” (Lutheranism, Anti-Judaism, and Bach’s “St. John Passion,” 1998, p.30).

Even when, at a more granular level, key terms are not already successively repeated in the gospel text, Bach manages to repeat phrases and individual words in a way that heightens the emotional effect of the hostile chorus. In this scene, for example, it’s not enough for the chorus just to sing “straight” the written gospel sentence “Wäre dieser nicht ein Übeltäter, wir hätten dir ihn nicht überantwortet” (“If this man were not an evil-doer, we wouldn’t have turned him over to you”), but rather the choral writing (Dover full score, p.47) specifically requires the altos, for instance, to hammer a single word five times in a row —“nicht, nicht, nicht, nicht, nicht” — in a way that sounds almost like an insult aimed at the slow-wittedness of the authorities.

For a moment, it may be permissible to imagine Bach having composed certain parts of the St. John Passion very differently. In a webinar on May 23, 2020, hosted by the Center for Early Music Studies at Boston University and devoted to the St. John Passion, musicologist Daniel R. Melamed slyly floated a possible alternative treatment of the Part 1 opening chorus that seems to fit the gist of the text better. And I feel that the chorus music of the trial, too, even while retaining the text and situation as they stand, could have been quite otherwise: perhaps with a slower, more deliberative tempo, or dynamics less raucous, or word-pointing accents less insistent, the priestly entourage could have been endowed with a measure of judicial gravitas as they seek the last resort of a death penalty. The crowd’s choral music did not have to be inflected quite so aggressively here, at the outset of the proceedings — boiling over immediately into insistently rising vocal lines — since the group is simply stating two self-evident points about the case: the defendant is considered to have committed a serious crime, and the priests lack the means to execute him for it.

Be that as it may, the hostile onstage choral statements from “the Jews” at this early point, though as yet relatively mild, are shocking nonetheless because they come so soon after the very same choir singers have just, in their other, devotional “role,” sung the opening chorale of Part 2, about “Christ, who makes us blessed” (text by Michael Weisse). But note that even the chorale itself serves a narrative of disparagement — describing Jesus’ trial as taking place before “gottlose Leut” (“godless people”) — a view that thereby creeps into the contemplative content of the Good Friday vespers.

•

SCENE 2 (INSIDE): FIRST INTERROGATION: KINGSHIP

(See a video clip, with Jeannette Sorrell conducting.)

Evangelist: . . . Then Pilate went back into the judgment hall and called Jesus and said to him:

Pilate: Are you the King of the Jews?

Evangelist: Jesus answered:

Jesus: Do you say this of yourself, or have others said this of me?

Evangelist: Pilate answered:

Pilate: Am I a Jew? Your people and the high priests have delivered you to me; what have you done?

Evangelist: Jesus answered:

Jesus: My kingdom is not of this world; if my kingdom were of this world, my servants would fight over this, so that I would not be handed over to the Jews; now however my kingdom is not from here.

Chorale

Ah great king, great for all times,

how can I sufficiently proclaim this love?

No human’s heart, however, can conceive

of a fit offering to you.

I cannot grasp with my mind,

how to imitate your mercy.

How can I then repay your deeds of love

with my actions?

Evangelist: Then Pilate said to him:

Pilate: Then you are a king?

Evangelist: Jesus answered:

Jesus: You say I am a king. I was born for this, and came into the world, that I might bear witness to the truth. Whoever is of the truth hears my voice.

Evangelist: Pilate said to him:

Pilate: What is truth?

COMMENTARY:

Pilate’s first question is not unexpected. A little earlier in the narrative, John had written: “ . . . the great crowd that had come to the feast, hearing that Jesus was coming to Jerusalem, took branches from the palm trees and went to meet him and cried out ‘Hosanna, blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord, the king of Israel!’” (John 12:12). The assertion of kingship was made by “the great crowd,” however, not by Jesus, who generally remained evasive or cryptic when questioned by officials on this matter.

Luther interprets this scene in terms of sedition: “The archscoundrels and godless knaves were able to bring no more serious charge against Christ than to accuse him of being King of the Jews. . . . The king of the Jews was the emperor, who had set his governor in charge of Jerusalem” (Luther’s Works, pp.208-9).

When asked if he is the King of the Jews, the prisoner has the calm self-assurance to talk back, and before answering he asks Pilate himself a question — essentially, Where did you get that idea? — as if the prefect were the one on trial, undergoing cross-examination. The accused’s aura of regal authority is to be understood as another mark of his true kingship. As throughout, John’s Jesus is somewhat more godlike (in his remarkable command of the situation), and perhaps somewhat less human (in not visibly dreading his death), than the figure we see in the other gospel Passions.

The astonishing thing about how John composed this scene, however, is the rhetorical skill with which Jesus easily defuses the issue: “My kingdom is not of this world.” When Bach’s chorus comes in with “Ah great king, great for all times,” they too are speaking of his otherworldly, eternal realm, the ideal world described in his ethical and moral teaching. Jesus repudiates any ambition for secular, political authority. The calming chorus gives the audience some breathing room, so they can pause to take in the larger ramifications of what Jesus has just said, with serene understatement, about his ethereal kingdom, before he and Pilate move on.

What Jesus articulates is not, or not only, an ancient version of the separation of church and state, but a realistic acknowledgment of how things stood within the polyglot Roman empire. A conquered nation could retain a measure of self-government and continue to worship its own gods so long as it acknowledged the hegemony of Rome, paid its taxes, and gave lip service to the Roman deities. Rome’s problem with the land of Israel was precisely that this nation of monotheists refused to acknowledge the “pagan” Roman gods, and still harbored aspirations for full, complete autonomy, which they’d lost in 6 BCE, when the system of Roman prefects and procurators was firmly established.

In John’s gospel what Jesus offers, instead, is an acceptance of secular, Roman rule over political matters, which will not interfere with his own religious, apolitical rule over the beliefs and ethical behavior of his followers.

When Jesus expresses this apolitical view in the judgment hall, Pilate is glad to hear it, but still confused: “Then you are a king?” Again, Jesus answers with a haughty certitude that impresses his listener: “I was born for this and came into the world that I might bear witness to the truth.” What kind of person can it be who knows, let alone explains, why they “came into the world,” as if a commando sent on a mission? Pilate may also be mystified by Jesus’ characteristic use of the term “the world” again (or “the cosmos,” in a recent translation), imputing global implications to their brief conversation. And the prefect shies away from the part about “the truth”; his question “What is truth?” could be either a sarcastic putdown of Jesus’ lofty rhetoric or, possibly, the first musings of a would-be philosopher.

Yet he does seem to acknowledge from here on that Jesus is truly a king — of the otherworldly realm the prisoner defined — and Pilate continues to speak of him as a king throughout the remainder of the trial, and even afterward.

•

SCENE 3 (OUTSIDE): PILATE FINDS JESUS NOT GUILTY; BARABBAS CHOICE

(See a video clip, with John Eliot Gardiner conducting.)

Evangelist: And when he had said this, he went out again to the Jews and said to them:

Pilate: I find no fault in him. However, you have a custom, that I release someone to you; do you wish now, that I release the King of the Jews to you?

Evangelist: Then they all cried out together and said:

Chorus: Not this one, but Barabbas!

Evangelist: Barabbas however was a murderer. Then Pilate took Jesus and scourged him.

COMMENTARY:

When Jesus repudiated secular authority, he divorced himself from political hotheads like Barabbas. As Luther said: “Barabbas was a rebel and a murderer. He was captured in open rebellion and had committed murder during the rebellion. . . . Pilate acknowledges that he would prefer to release Christ as a preacher of the truth and instead put Barabbas to death as a rebel and murderer” (Luther’s Works, pp.217-18).

But the distinction between political and spiritual kingship is not getting through to the crowd. By bluntly calling Jesus “the King of the Jews,” Pilate merely antagonizes the onlookers, who didn’t have the benefit of hearing the “not of this world” speech during the first interrogation.

Pilate’s Barabbas ploy having failed, he tries another stratagem for avoiding the execution of Jesus: scourging. In the usual course of Roman condemnation, scourging took place as a necessary prelude to death, followed shortly after by crucifixion itself, and in Matthew’s and Mark’s gospels the scourging is inflicted only after Jesus has been sentenced. But in John, scourging is put forward as an alternative to crucifixion. Pilate has Jesus whipped to placate the priests with a lesser punishment which, though severe, was not usually fatal. Scene 5 will show how his plan works out.

In the meantime, Bach builds up Scene 4 into one of the richest musical episodes in the entire work, as he explores the ramifications of the flagellation itself, rather than just Pilate’s tactics.

•

SCENE 4 (INSIDE): SOLDIERS SCOURGE JESUS

(See a video clip, with John Butt conducting.)

Arioso (Bass):

Contemplate, my soul, with anxious pleasure,

with bitter joy and half-constricted heart,

your highest good in Jesus’ suffering,

how for you, out of the thorns that pierce him,

the tiny “keys of Heaven” bloom!

You can pluck much sweet fruit

from his wormwood;

therefore gaze without pause upon him!

Aria (Tenor):

Consider, how his blood-stained back

in every aspect is like Heaven,

in which, after the watery deluge

of the flood of our sins was released,

the most beautiful rainbow

as God’s sign of grace was placed!

Evangelist: And the soldiers wove a crown of thorns and set it upon his head, and laid a purple mantel on him, and said:

Chorus: Hail to you, dear King of the Jews!

Evangelist: And gave him blows on the cheek. . . .

COMMENTARY:

John places this violent episode at the exact middle of his drama — between the two “not guilty” scenes — as the central turning point of the action. Bach, in turn, marks this crux with two vocal compositions as strange as they are moving.

The pause in the narrative for the bass arioso and tenor aria is the imaginative space of time during which Jesus is flogged. In an astonishing act of creative imagination on Bach’s part, the bass arioso (sung in this video clip by the Pilate bass) is among the tenderest and most contemplative of his vocal compositions: its delicate, intimate lute brings in a soft lyricism, while its words speak of the drops of blood from the wounding thorns of the crown as letting tiny flowers blossom forth, bearing “sweet fruit” — the occasion for “bitter joy.” Likewise, the ensuing tenor aria compares the curved and blood-colored whip marks on Jesus’ back to the overarching rainbow of the covenant.

These samples of figurative language are among the more extreme, some might say grotesque, in the popular Lutheran piety that Bach set to music. The poetic texts of the bass arioso (“Betrachte, meine Seel”) and the tenor aria (“Erwäge, wie sein blutgefärbter Rücken”) are both by Barthold Heinrich Brockes, known for his graphic imagery; other poems in this Passion are by Michael Weisse (see the chorale discussed above), Christian Heinrich Postel, or anonymous. But as Andreas Loewe notes, “Brockes’ florid Baroque poetry is toned down by the librettist of the St. John Passion to create a more intimate and personal appeal to the human soul” (Johann Sebastian Bach’s “St. John Passion” {BWV 245}: A Theological Commentary, 2014, p.211)

Readers familiar with the English poets of the seventeenth-century Metaphysical school, sometimes called the Baroque poets (such as John Donne, George Herbert, Thomas Traherne, and Richard Crashaw) will not be surprised by what may seem like metaphorical excesses in Bach’s nonbiblical texts. For the unusual figures of speech found in some of the arias are much like what in English poetry are called “conceits,” famously defined by literary critic Helen Gardner: “a conceit is a comparison whose ingenuity is more striking than its justness” (The Metaphysical Poets, 1961, p.xxiii). For instance, in the poem “The Weeper” Crashaw writes of Mary Magdalene’s two tear-filled eyes: “And now where’er he strays / Among the Galilean mountains, / Or more unwelcome ways, / He’s follow’d by two faithful fountains; / Two walking baths, two weeping motions; / Portable and compendious oceans.” Some of the nonbiblical texts set by Bach are replete with such conceits, of which the bass arioso and tenor aria furnish remarkable examples.

Then, as we return to the “Trial Before Pilate” drama, Luther takes the unusual step of pointing to a theatrical artifice within the trial as written by John; Luther sees the Roman soldiers as actors in a play: “Because Christ had confessed to Pilate that he is a king, and yet his kingdom is not of this world, the soldiers exploited this confession, as if saying ‘He himself confessed to being a king. Therefore, we will adorn him and crown him as a king.’ Thus they began to act out a Carnival play with him, by dressing him in royal clothes and crowning him with thorns” (Luther’s Works, p.294). It’s telling that Luther can see the trial as displaying calculated histrionics. What the soldiers have in mind specifically is something like the Shrovetide fair, presided over by a “king of fools” who mocked authority by inverting the hierarchy of official rule.

That festive occasion may be responsible for the taunting, jaunty tune with which the chorus, now playing the Roman soldiers rather than the outdoor crowd, sings “Hail to you, dear King of the Jews!” to their victim.

•

SCENE 5 (OUTSIDE): PILATE FINDS JESUS NOT GUILTY; “BEHOLD THE MAN”

(See a video clip, with John Eliot Gardiner conducting.)

Evangelist: . . . Then Pilate went back outside and spoke to them.

Pilate: Behold, I bring him out to you, so that you recognize, that I find no fault in him.

Evangelist: Then Jesus went out and wore a crown of thorns and a purple mantel. And Pilate said to them:

Pilate: Behold what manner of man this is!

Evangelist: When the high priests and servants saw him, they screamed and said:

Chorus: Crucify, crucify!

Evangelist: Pilate said to them:

Pilate: You take him away and crucify him; for I find no fault in him!

Evangelist: The Jews answered him:

Chorus: We have a law, and according to that law he should die; for he has made himself the Son of God.

COMMENTARY:

Pilate sought to appease the high priests by flogging Jesus, and appeal to their sense of mercy by showing him publicly in a bloodied state. The prefect has made a placating gesture, hoping to avoid crucifying someone he dimly understands to be a king.

Luther’s German phrasing of this scene’s famous sentence — “Sehet, welch ein Mensch!” — can be puzzling. In English, we’re used to reading “Behold the man!” But Luther’s German has often been translated as “Behold, what a man!” (anachronistic to some, with its incongruous sense of a he-man). The editors of Luther’s Works opt for “Behold what manner of man this is!” (p.225).

In John’s telling, Pilate again reminds the priests, if elliptically, that they have no right to crucify, a penalty only Rome can carry out (already made clear in Scene 1).

As Adele Reinhartz points out in her detailed annotations of this gospel: “In John it is the Temple party, and not the people as a whole, who call for crucifixion; contrast Matt. 27:25” (The Jewish Annotated New Testament, rev. 2017, p.218), meaning not only the line specifically spelling out “the high priests and servants” but also the group’s next line, tagged only with John’s shorthand term, “the Jews.” And here the Temple party dramatically changes its tactics, and instead of charging Jesus with pretending to secular, political authority, the high priests now suddenly bring up the previously unmentioned subject of blasphemy: “He has made himself the Son of God.” The singing of these words becomes a tirade.

As Luther preaches: “To make oneself the Son of God was such a great sin among the Jews that there could be none greater. . . . Yet such an accusation of blasphemy meant nothing to Pilate, since he knew nothing of Jewish law. And even if the Jews had proven this and had truthfully brought against Christ the charge that he had committed blasphemy, Pilate still could have said: ‘Why do you Jews violate your own law? Your law commands that a blasphemer should be stoned, not crucified . . . crucifixion is not the punishment for blasphemy even according to your law’” (p.229).

Luther’s talent for dramatization, and the manufacturing of imaginary dialogue, rivals John’s own in a passage like this. But in the heat of his fervor, Luther contradicts himself — in the same paragraph saying that Pilate “knew nothing of Jewish law” and yet two sentences later having his imaginary Pilate accurately cite from memory the exact Jewish penalty for blasphemy.

•

SCENE 6 (INSIDE): SECOND INTERROGATION: POWER

(See a video clip, with Jeannette Sorrell conducting.)

Evangelist: When Pilate heard this, he became more afraid and went back inside to the judgment hall and said to Jesus:

Pilate: Where do you come from?

Evangelist: But Jesus gave him no answer. Then Pilate said to him:

Pilate: You don’t speak to me? Don’t you know that I have the power to crucify you, and the power to release you?

Evangelist: Jesus answered:

Jesus: You would have no power over me, if it were not given to you from above; therefore, he who has delivered me to you has the greater sin.

Evangelist: From then on Pilate considered how he might release him.

Chorale:

Through your prison, Son of God,

must freedom come to us;

Your cell is the throne of grace,

the sanctuary of all the righteous;

for if you had not undergone servitude,

our slavery would have been eternal.

COMMENTARY:

It may seem odd that Pilate asks Jesus “Where do you come from?”

He is not, however, asking whether Jesus is from Galilee or from Judea, although that was indeed a point of contention in Luke’s gospel account of the trial (Luke 23:5-6): “[The leading priests] became insistent. ‘But he is causing riots by his teaching wherever he goes — all over Judea, from Galilee to Jerusalem!’ ‘Oh, is he a Galilean?’ Pilate asked. When they said that he was, Pilate sent him to Herod Antipas, because Galilee was under Herod’s jurisdiction, and Herod happened to be in Jerusalem at the time.” In Luke, Pilate plays the Galilee card, hoping to unload this troublesome case onto Herod Antipas, Tetrarch of Galilee. But Herod, politely, sends the offender back.

In his own gospel, John has a wholly different idea in mind. In asking where Jesus comes from, Pilate is referring back to Jesus’ earlier remark, “My kingdom is not of this world.” Pilate is now asking, in effect: If your kingdom is not of this world, then what world are you from?

He asks this of Jesus because he’d been stopped dead in his tracks by the assertion, at the end of the previous scene, that “He has made himself the Son of God.” Like all Romans, Pilate lived in what historian Keith Hopkins called “a world full of gods.” They were everywhere and, problematically, they sometimes mated with humans and begot demigods, such as Hercules (son of Jupiter and Alcmene). Pilate apparently is now worried that Jesus may be such a one, hence his question.

Jesus’ tart response to Pilate — referring pointedly to “power . . . from above” — is not especially comforting, for he thereby accuses the prefect of sin, in allowing an innocent man to be executed. It may be heartening to hear that somebody else “has the greater sin,” presumably the high priests and/or Judas Iscariot. But still, Pilate’s guilt for his impending act of killing an innocent man has now been called out to his face by a lowly itinerant preacher from the boondocks who dares to instruct him on the fine points of judicial sentencing. Pilate, again, finds himself on trial, and liable to be punished no matter how the verdict turns out: he will be punished by political forces if he doesn’t kill Jesus (that is, by Rome, if the priests complain that the prefect tolerates a rival king; or by the priests themselves, in the form of possibly rebellious future behavior). Or, if he does go through with killing Jesus, he could be punished directly by whatever god may be Jesus’ father. In introducing this consideration, this scene brings to the fore John’s characteristic view of Jesus as a more overtly godlike figure than in the other gospels.

No wonder Pilate resolves to set the prisoner free, if he can. His resolution, however, lasts only two or three lines of his dialogue.

In the meantime, the chorale points out how the prisoner’s kingship remains manifest and transforms whatever place he happens to be in: “Your cell is the throne of grace, the sanctuary of all the righteous.” The prison where he’s held contains a “throne” and, like the Temple itself, houses the holy “sanctuary.”

•

SCENE 7 (OUTSIDE): PILATE DELIVERS JESUS TO BE CRUCIFIED

(See a video clip, with Roger Norrington conducting.)

Evangelist: The Jews, however, screamed and said:

Chorus: If you let this man go, you are not a friend of Caesar; for whoever makes himself a king is against Caesar.

Evangelist: When Pilate heard this, he brought Jesus outside and sat upon the judgment seat, at the place that is called the High Pavement, in Hebrew however: Gabbatha. But it was the Sabbath-day at the Passover at the sixth hour, and he said to the Jews:

Pilate: Behold, this is your king!

Evangelist: But they shrieked:

Chorus: Away, away with him, crucify him!

Evangelist: Pilate said to them:

Pilate: Shall I crucify your king?

Evangelist: The high priests answered:

Chorus: We have no king but Caesar.

Evangelist: Then he delivered him to be crucified. They took Jesus and led him away. And he carried his cross, and went up to the place that is called the Place of the Skull, which is called in Hebrew: Golgotha.

Aria (Bass) and Chorus:

Hurry, you tempted souls,

come out of your caves of torment,

hurry — where? — to Golgotha!

Take up the wings of faith,

fly — where? — to the hill of the cross,

your salvation blooms there!

Evangelist: There they crucified him, and two others with him on either side, Jesus however in the middle. Pilate however wrote a signpost and set it upon the cross, and there was written on it: “JESUS OF NAZARETH, THE KING OF THE JEWS.” This signpost was read by many Jews, for the place where Jesus was crucified was near the city. And it was written in the Hebrew, Greek and Latin languages. Then the high priests of the Jews said to Pilate:

Chorus: Do not write: “The King of the Jews,” rather that “He said: ‘I am the King of the Jews.’”

Evangelist: Pilate answered:

Pilate: What I have written, I have written.

COMMENTARY:

At the trial’s end, the high priests outmaneuver their Roman ruler; unexpectedly, they drop the relatively esoteric matter of blasphemy as quickly as they had brought it up, and revert to their winning issue of governmental authority. Through their public declaration of political allegiance, “We have no king but Caesar,” they manage to call Pilate’s own allegiance into doubt: they blackmail him with a thinly veiled threat to complain to the emperor about undue leniency toward a rival king. Only then does he give in.

Several incidents in the known historical record of the prefect’s rule might have led the evangelist to portray Pilate going down in final capitulation. According to Josephus (Jewish Antiquities 18:55-59), the priests had bested Pilate before, in the notorious “episode of the standards” (26 CE), when they forced him to back down after he’d brought standards with images of the emperor into the Fortress of Antonia, adjacent to the Temple. Even more damagingly, in the “episode of the shields” (31 or 32 CE), as reported by Philo (Embassy of Gaius 38:299-305), Pilate hung golden shields, inscribed with the epithet “son of god” for the emperor Tiberius, inside the courtyard of the prefect’s Jerusalem palace, which led the priests, through Herodian princes, to protest to Tiberius himself, who impatiently ordered Pilate to move the shields to the official prefectural residence, in Caesarea Maritima. (See Paul L. Maier, “The Episode of the Golden Roman Shields,” 1969, for the view that in this “one bizarre incident . . . Pilate seems more sinned against than sinning.”)

As the priests’ new moment of triumph over Pilate approaches, Bach gives their first two choral passages in this scene a certain fugal excitement, suggesting perhaps an unseemly gleefulness at having at last forced a death sentence. In their third chorus, cynically “accepting” Caesar as their only king, the priests strategically avoid mentioning that the only true king of the land of Israel is the God of Moses.

Note that, in writing the outcome here, John meticulously records the exact date and time: that is, the trial ends at noon on the Day of Preparation, with the Passover itself beginning at sundown. Identifying the specific day and time symmetrically reminds us of the very first scene, in which Caiaphas and the other priests “did not go into the judgment hall, so that they would not become unclean; rather that they could partake of the Passover.”

The temporal specifications are exact because the logic of John’s account turns precisely on date and time. One of the great peculiarities of his gospel, setting it firmly apart from the synoptic gospels (Matthew, Mark, and Luke), is his adjustment to the calendar of what Christians generally call Holy Week. The synoptics present the Last Supper as Jesus celebrating the paschal feast with his disciples on the Passover, where he establishes the related sacrament of eating the eucharist; he is then crucified the following afternoon (15th of Nisan, in the Jewish calendar). John, however, has his own agenda. In John, the supper with the apostles is a regular meal, which the gospel text indicates takes place “before the Passover,” and John never mentions the eucharist anywhere; Jesus is then brought before Pilate during the morning of the Day of Preparation, with the trial concluded at noon (14th of Nisan).

In other words, because in the Jewish calendar a day extends from sunset to sunset, Jesus’ Last Supper, arrest in the garden, trial, and death all take place on one and the same day. In the synoptic gospels, that day is the 15th of Nisan (i.e., April 4, 33 CE). In John’s gospel, that day is the 14th of Nisan (i.e., April 3, 33 CE).

John’s change to the calendar date of the crucifixion has enormous theological implications, for it means that Christ, the Lamb of God, dies on the cross in the afternoon of the Day of Preparation — just when the priests are slaughtering the lambs in the courtyard of the Temple for the Passover feast, which will take place that evening.

For what was emerging as a new religion, seeking among other things to distinguish itself from the Judaism of the first century CE, this changed everything. With the Lamb of God offered up as the ultimate sacrifice, it could now have been argued that there was no longer any need for the Jewish priests to continue slaughtering lambs at the Temple. In effect, John has Jesus, through his sacrifice, destroy one of the central, defining features of the Temple: its role as the place of sacrifice to God, which Jesus had already disrupted at the so-called Cleansing of the Temple. In this sense, Jesus did indeed “destroy” the Temple: “But the temple he had spoken of was his body” (John 21:20). Destroying the temple of his body, crucified on the Day of Preparation in place of slaughtered lambs, he thereby, it is asserted, rendered moot the sacrificial function of the actual Temple.

John has Jesus spend so much time talking about the metaphorical destruction of the Temple in part because, as everyone of John’s era of 100 CE of course knew, the Temple of Jerusalem — that is, officially, the Second Temple, built by Herod and “cleansed” by Jesus — had in fact been destroyed by the Roman army in 70 CE.

John takes advantage of what is sometimes called “retrojection,” the writer’s device of projecting a later event onto the past: he uses his knowledge of the Temple’s ultimate fate to allow its historical demise to be “foreshadowed” in Jesus’ preaching in 30-33 CE. That is, John has Jesus knowingly offer the new temple of his body as a substitute for the ill-fated Temple of Jerusalem that would vanish four decades after his death.

The Politics of Pilate’s Signpost: “JESUS OF NAZARETH, THE KING OF THE JEWS”

Although Bach’s trial scene proper ends with the transitional bass aria that sends the listener on the “flight” to Golgotha, nonetheless, in the extract above I’ve included as well the exchange between Pilate and the high priests about the signpost on the cross. Here, they continue their argument. Having lost in the outcome of the trial, Pilate puts up a sign reasserting his view of the man. And defying the priests, he refuses to change the precise wording when they demand: “Do not write: ‘The King of the Jews,’ rather that ‘He said: I am the King of the Jews.’” John, too, wants one last opportunity to highlight Christ’s regal status, moving toward the close of his account of the death of a king.

As a cautionary political statement, Pilate’s signpost appears in three official languages — Hebrew, Greek, and Latin — though not in the vernacular Aramaic spoken by Jesus and most other Second Temple-era Jews. In citing this linguistically complex public announcement, recent studies, as mentioned earlier, prefer to use in Jesus’ “title” a word from geopolitics rather than religion. Shaye J.D. Cohen says of Jesus, “As ‘king of the Jews’ (perhaps ‘king of the Judeans’ would be better) he was sentenced to death by the Romans” (From the Maccabees to the Mishnah, 3rd ed., 2014, p.231). And in David Bentley Hart’s The New Testament: A Translation (2017), occasionally cited above, Pilate’s question “Are you the king of the Jews?” is newly translated instead as: “Are you the king of the Judaeans?”

The signpost, retranslated as “JESUS OF NAZARETH, THE KING OF THE JUDEANS,” is further adjusted in Hart’s translation to read “JESUS THE NAZOREAN THE KING OF THE JUDAEANS.”

Deploying the word “Judean” (also spelled “Judaean”) in this scene has the effect of refocusing the proceedings on a king’s secular, national, territorial authority — his power over places, with place-names like Judea or Galilee or Rome — on which grounds the high priests successfully prosecuted their case.

The contrary argument made by Jesus, however, was based on an (otherworldly) king’s authority over no places — un-places “not of this world” — as suggested in our English word utopia, which means “no place.” Jesus, it could be said, claimed to rule over a utopian domain of ideal ethics. We may have to find a new way of naming the topography of his native realm amid the scholarly preference for historical place-names.

Curiously, Pilate’s retranslated signpost declares that a man from Nazareth, and therefore a Galilean — a subject of Herod Antipas, Tetrarch of Galilee — is the true ruler of Judea, a jurisdiction he’s not even from.

Pilate’s Afterlife

In the score of the St. John Passion, Jesus and Pilate are both classified as basses, as was conventional. There are no solo arias for bass at all in Part 1. Yet when Pilate steps on stage in Part 2, bass arias begin to appear: the tender arioso at the scourging; the “To Golgotha” aria at the end of the trial; and the “My dear Savior” aria, sung in direct address to Christ on the cross. Within the economy of performance practice, often the bass who sings Pilate also sings one, two, or all three of these.

What are the artistic ramifications of a bass voice associated with Pilate taking on the fervent prayers of the faithful in these three numbers? In his sermons, Luther provides a clue: he does not stop at calling Pilate “a reasonable man, and a wise Gentile and Roman,” and goes on to hail him for being “God’s hired man and servant without knowing it” (Luther’s Works, pp.222, 227).

Given that Pilate is Jesus’ one and only defender in the trial, it’s not so surprising that Coptic and Ethiopian churches, which believe he became a Christian, venerate the prefect as a martyr and saint; his feast day is June 25. Even in John, Pilate looks like a plausible candidate to be Jesus’ first gentile Roman convert: he has listened closely to Jesus’ words and championed him before a hostile public.

Bach’s musical opportunities for the bass also bring out the prefect’s capacity for self-transformation, especially as portrayed in Christian Gerhaher’s sympathetic performance as Pilate. He is shown in an unusual intimacy of exchange with Jesus in the trial — and then goes on to sing the last bass aria in the supplicant posture, and with the wonder, of a new believer in Christianity, a highlight of the Peter Sellars/Simon Rattle production.

Helping to draw the St. John Passion to its conclusion, the authoritative bass soloist possesses the conspicuous credentials of having sung the presiding figure of Pilate. In the closing section, after Jesus has expired, the bass joins the soprano, alto, and tenor soloists in a series of “voices of the believers” arias that redirect the congregation’s attention away from death and toward the living church they belong to.

(July 2020)

Selected Video Recordings of the St. John Passion

Asterisk (*) indicates subtitles.

Karl Richter, Münchener Bach-Orchester (1970)*

Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Concentus Musicus Wien (1985)

Masaaki Suzuki, Bach Collegium Japan (2000)

Sigiswald Kuijken, La Petite Bande (2012)

John Eliot Gardiner, English Baroque Soloists (2013)*

Itay Jedlin, Festival d’Ambronay (2014)

Roger Norrington, Zürcher Kammerorchester/ZKO (2014)*

Peter Sellars/Simon Rattle, Berliner Philharmoniker (2014)*

David Chin, Malaysia Bach Festival (2015)

Peter Dijkstra, Concerto Köln (2015)

Bernd Eberhardt, Göttinger Barockorchester (2015)

Kay Johannsen, Stiftsbarock Stuttgart (2015)

Frieder Bernius, Barockorchester Stuttgart (2016)

Jeannette Sorrell, Apollo’s Fire (2016)*

John Butt, Dunedin Consort (2017)*

Jeffrey Grossman, TENET and the Sebastians (2017)

Jos van Veldhoven, Nederlandse Bachvereniging (2017)

Barnaby Smith, Academy of Ancient Music (2019)

Philippe Herreweghe, Collegium Vocale Gent (2020)