James Leggio

In his recent book The Impossible Art: Adventures in Opera (2021), the composer, conductor, and writer Matthew Aucoin develops an intriguing point: opera’s greatness as an art form lies in what he calls its “impossibility.”

Opera is impossible and always has been. Impossibility is baked into the art form’s foundations. The operatic ideal, an imagined union of all the human senses and all art forms — music, drama, dance, poetry, painting — is itself an impossibility. But this impossibility is productive and even liberating: all of opera’s bizarre and beautiful fruits, its cathartic embodiments of the extremes of human psychology, its carnivalesque excesses, its improbable moments of intimate revelation, stem from artists’ ongoing search for this permanently elusive alchemy.

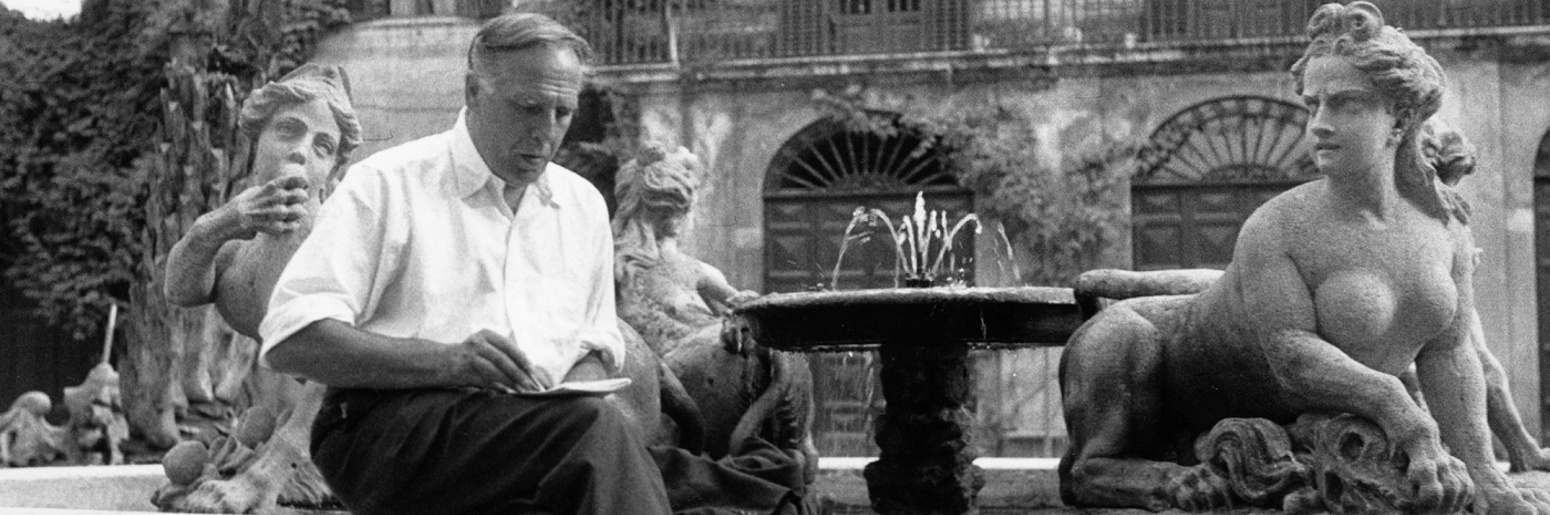

Of his many chapters devoted to individual operas, the one on Igor Stravinsky and The Rake’s Progress (1951), among the last major works of the composer’s so-called neoclassical period, raises especially compelling issues. The Rake turns out to be a prime example of opera’s capacity for “improbable moments of intimate revelation.”

That’s the point I want to pursue here. For, remarkably, the opera’s psychologically rich libretto, by W.H. Auden and Chester Kallman, seems to take on the “impossible” task of disclosing an intimate revelation — by telling an allegorical story about its own creators.

The Rake as a Private Allegory

After Stravinsky saw William Hogarth’s series of engravings A Rake’s Progress (1735) on exhibition in 1947, he decided to commission an opera libretto based on the dramatic “progress” of Hogarth’s libertine, from wealth to destitution and eventual madness. When Auden and Kallman signed on and began to spin out ideas for the text, they made up two major new characters not in Hogarth: a devil, named Nick Shadow, who evoked the familiar plot formula of the Faustian bargain; and a circus-artiste, dubbed Baba the Turk, whose role in the proceedings is much harder to define.

Aucoin speaks admiringly about “the way Stravinsky imbues Auden and Kallman’s characters, some of whom look a little stilted on the page, with life and warmth.” (The librettists’ plot summary is available here.) The Rake’s main emotional dynamic as written out in the libretto — the “love triangle” of naïve Tom Rakewell, devoted Anne Trulove, and theatrical Baba the Turk — needed music to bring it to life:

A character as impregnably virtuous as Anne does risk being a bore, and I’m afraid there’s a whiff of misogyny in Auden and Kallman’s treatment of her: I can’t help but hear, in her ever-righteous lines, the muffled sound of two male librettists trying to stifle their giggles at the idea of such an improbably saintly woman. (In a reflection on The Rake published a decade after the opera’s premiere, Kallman snickeringly points out that the only thing Anne ever says to her father is “Yes, Father” — “but then, of course, she is a very good girl.”) . . . This blunt fixity of purpose might look one-dimensional on the page, but don’t judge poor Anne just yet — she is the character who is most thoroughly transformed by Stravinsky’s music. And the hint of mockery in the librettists’ depiction of Anne was, to some degree, inwardly directed: the Auden scholar Edward Mendelson has pointed out that Auden, throughout his relationship with Kallman, himself played the long-suffering Anne to Kallman’s recalcitrant Rake.

Calling Anne “impregnably virtuous” carries a faint whiff of Kallman’s own patronizing view of her. Aucoin is on firmer ground in citing Edward Mendelson, editor of The Complete Works of W.H. Auden (Princeton University Press), who offers a fuller account of the drama’s governing structure.

Mendelson illuminates the inner dynamics of The Rake’s Progress, in the second half of his critical biography, the volume called Later Auden (1999), as well as in his annotation of The Rake’s text in the volume Libretti and Other Dramatic Works, 1939-1973 (1993), in Auden’s complete works. Not only is the Anne/Tom scenario “a private allegory about Kallman’s relations with Auden,” but it also leads on to Baba the Turk:

The allegory was rendered more complex by the division of labor in the writing. Auden wrote most of Rakewell’s faithless lines while Kallman wrote most of Anne’s faithful ones. Auden as lover appears in the libretto as Anne Trulove, but Auden as artist appears as Baba the Turk. Her beard is her gift, and she recognizes it as her vocation — a glory, not a curse. The beard, Auden said in a broadcast, “represents her genius, something which makes her what she is and at the same time cuts her off from other people.” In accepting Rakewell’s [marriage] proposal, her mistake “is that she tries to fit into an ordinary family life, to be an ordinary person, and of course the whole thing breaks down.” Her triumphant exit — when she goes back to dominate the stage after her “self-indulgent intermezzo” with Rakewell — crushes into cowed subservience the auctioneer who had tried to reduce her unique exotic treasures (each one given by an admirer whom she names) to the anonymous numbered lots of a sale. Before she leaves she restores Anne to hope and encourages her search for the ruined, absconded rake.

This private allegory underlying Tom, Anne, and Baba makes The Rake a work of “intimate revelation.” Yet though the Anne/Auden and Tom/Kallman parallels seem clear enough, what are we to make of Mendelson’s tantalizing identification of Baba the Turk with “Auden as artist”?

To unpack that insight, let’s spend some time with Baba.

Baba’s Beard

In transforming Hogarth’s images into an opera libretto, Auden and Kallman did away with the wealthy “ancient lady” whom the Rake espouses for financial gain in The Marriage, number 5 of the Rake engravings, and replaced her with Baba. Kallman later said of his work on the libretto with Auden, “the day that Baba the Turk was born and named, we both laughed until we could no longer stand up straight.”

Roger Savage describes her noteworthy physical feature, in the ENO Guide to The Rake: “Tom Rakewell’s ill-matched bride, the circus-artiste Baba the Turk . . . sports, as Auden puts it, ‘a magnificent Assyrian beard.’” Presumably like this one:

In 1958, Auden and Kallman wrote an explanatory verse prologue to the opera, an our-story-so-far introduction, to be spoken to the audience by the singer playing Nick Shadow, before a broadcast on BBC Television of only the last five scenes. The prologue anticipates listeners’ questioning why Baba is in the opera at all, let alone as a marriage partner:

Perhaps you ask, dear viewers, how this man

Could think of marriage and not think of Anne

Who is, I grant, a lovely loving She

While Baba, to be candid, is — you’ll see.

You don’t need a rhymer’s license to figure out that the last line, instead of breaking off with a dash before the end, could have read “While Baba, to be candid, is a He.”

Tom’s shifting preference from Anne to Baba is made plain upon Baba’s entrance (Act II, Scene 2), as described by Aucoin. (Watch a video clip of this scene, from the Glyndebourne Festival in 1975.)

As often as not, Stravinsky ignores the “recitative” marking altogether, transmuting a businesslike chunk of prose into a stretch of beguiling melody. Here, for example, is Baba the Turk’s first entrance, in which she imperiously orders Tom to help her out of her carriage:

ORCHESTRAL RECITATIVE

BABA (interrupting with vexation): My love, am I to remain in here forever? You know that I am not in the habit of stepping from my sedan unaided. Nor shall I wait, unmoved, much longer. Finish, if you please, whatever business is detaining you with this person.

As admirers of Mozart’s operas, Auden and Kallman probably had something specific in mind: a series of parlando outbursts, interrupted by slashing gestures from the orchestra (“My love [SLASH], am I to remain in here forever [SLASH]?” etc.). But Stravinsky takes the opposite tack: his setting isn’t really recitative at all, but rather a sweetly lyrical line in which two bassoons, warbling voluptuously in the instrument’s pungent upper register, wind around Baba’s voice like a pair of pet weasels.

Paul Griffith, in his book on The Rake, published in 1992, analyzes the music of Baba’s entrance from a slightly different angle, while taking us from this initial moment to her part in the trio and the scene’s finale:

Her little arioso, absurdly featuring a pair of bassoons, is in D major, already established as her key in the dry recitative of Act II scene 1 where Tom and Shadow discussed her for the first time. . . . [In the trio:] In parallel verses Anne and Tom . . . [c]ome together at two significant points, first on the word “never”, in roulades which promise to cadence and do not, and then finally in minor thirds on the words “for ever”. The third voice is that of Baba, who expresses her irritation in her own quicker tempo.

The scene ends with a grand saraband, as Tom escorts the veiled Baba to the entrance of their home, amid eager onlookers. The episode as a whole gradually increases in dramatic tension, leading ultimately to the crowning “reveal,” when Baba turns to the crowd and for the first time shows her fabled beard.

Whose Voices Are Whose?

To warrant such a celebrity apotheosis, when Baba becomes this opera’s diva, what (or whom) should her singing voice sound like?

We’ll return shortly to the overall question of who’s who within the libretto’s allegory of Tom, Anne, and Baba. But for a moment, let’s gather some related evidence, by considering who’s who among the chosen models for these characters — purely as singing voices. Whose voices are whose?

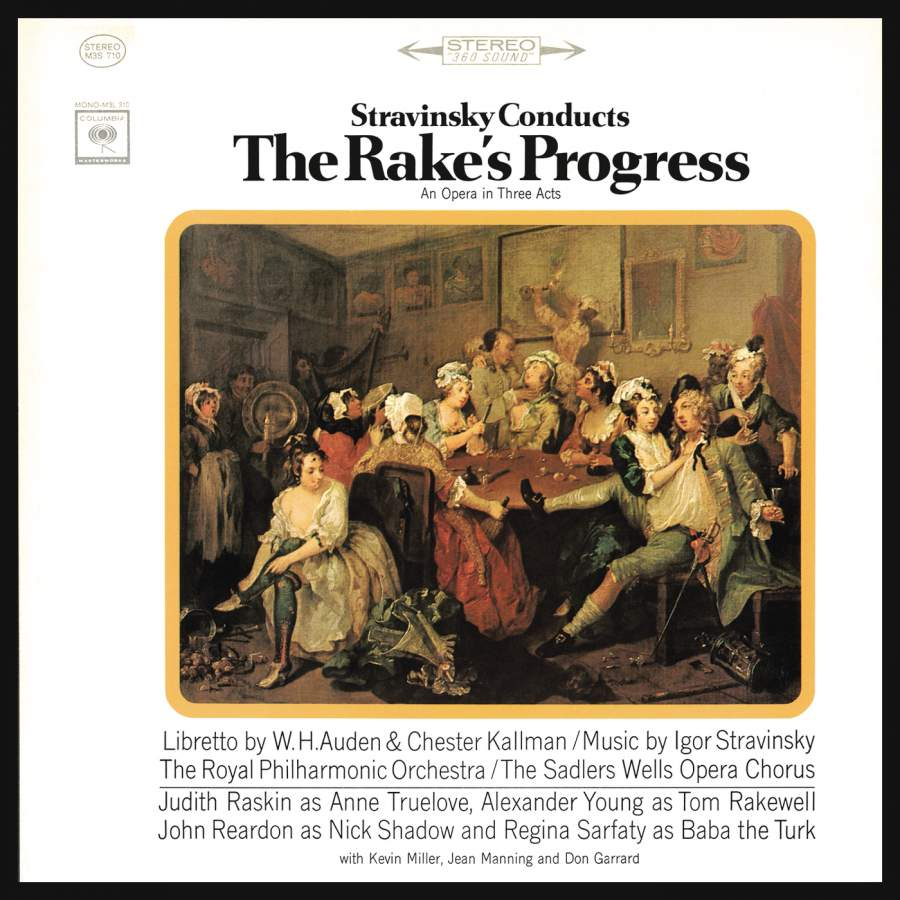

For the libretto booklet included with the Columbia Records LP set of The Rake, released in 1964, Kallman wrote a note, “Looking and Thinking Back” (reprinted in the Libretti volume of Auden’s complete works). The note lists the librettists’ chosen vocal models:

There was, now that I think of it, one more thing we provided Stravinsky with — an index of vocal types. He had asked us, when the libretto was completed, whether any particular voices or timbres of voice had been in our minds during our writing of the various roles. There had been. And so we loaned him a record album with discs of [Eleanor] Steber (Anne), [Ebe] Stignani (Baba), [Jussi] Bjoerling (Tom) and [Willi] Domgraf-Fassbaender (Shadow). I have never asked him, but I am fairly certain that these voices figure in the timbres of the score. More certainly, Baba’s coloratura, conceived in terms of Stignani’s range and evenness of intonation, clearly characterizes her with the same uncaricaturized brio that we wished her words to convey. Also, and more important, the over-all vocal thinking on the part of all three collaborators makes The Rake’s Progress something much more than the polemic anti-Music-Drama that it is too often hailed or dismissed as: it is a tribute to opera in much the same way that Apollon Musagète is a tribute to the dance.

Though it was unlikely that the librettists’ choices would or even could sing this opera onstage — and not simply because only one of them was a native speaker/singer of English — their selection hints at the sound qualities the creative team was listening for, in devising a major work of vocal art. The specific timbre, technique, and musical phrasing, the audible identity of each model as a particular singer, permeate the roles as composed.

It may surprise us at first that only two of the four singers mentioned were known for their Mozart, despite the importance of Don Giovanni as a period exemplar for The Rake. But with Stravinsky composing in a lively potpourri of historical manners, forming overall “a tribute to opera” as an art form, the singers needed to be equipped for the many other operatic styles that pop up in the mélange from time to time as well. Heather Wiebe expresses this point succinctly in “The Rake’s Progress as Opera Museum”:

The opera’s distinctive secco recitative is the most salient trace of Mozart’s musical world. But with its set-piece organization, its rage arias and cabalettas, folklike tunes and sober choruses, this music strays across the entire operatic tradition from Monteverdi and Handel to Rossini and Verdi, with forays into Bach cantatas and Handel oratorios as well as The Beggar’s Opera.

To cope with these wide-ranging vocal demands, the librettists chose some of the most versatile singers of their time. Let’s first look at the other principals, and then come back to Baba.

The American soprano Eleanor Steber had been singing leads at the Metropolitan Opera since 1940 and was known for her Mozart roles, among them Pamina in The Magic Flute and the Countess in The Marriage of Figaro; this TV appearance from 1952 shows her as the Countess, singing “Porgi, Amor” (watch clip). Her French roles are represented by another performance from 1952, “Depuis le jour” (watch clip) from Charpentier’s Louise. In both, she displays the strong yet silvery tone, elegant sense of line, and impeccable diction that were her hallmarks. Steber would certainly have been well-equipped not only for the grand Handelian scena comprising Act I, Scene 3 of The Rake, but also for the poignant lyricism of the Bedlam scene (Act III, Scene 3). Her voice’s ability to sustain a long arc of sorrow was clear in her radio broadcast of Madama Butterfly from the Met in 1949.

The choice of the renowned Swedish tenor Jussi Bjoerling, with his reliably gorgeous spinto voice, indicates that sheer glory of tonal splendor, along with freely ringing top notes, defines the nature of Tom Rakewell the singer: as Wiebe points out, his arias “Love, so frequently betrayed” and “Vary the Song,” along with his Adonis music in the Bedlam scene, “All count among the most self-consciously beautiful moments of the opera.” Not a noted Mozartian, though early in his career Bjoerling did sing Don Ottavio in Don Giovanni, he was far better known for such spectacular fare as Calaf’s aria “Nessun dorma!” from Puccini’s Turandot, here heard in a 1943 radio broadcast (listen to clip). On stage, Bjoerling had a long history of making a deal with the devil, for many seasons taking the title role in Gounod’s Faust (watch clip). Regarding his suitability for an English-language part like Tom Rakewell, the tenor’s lightly accented rendition of Stephen Foster’s “Jeannie with the Light Brown Hair” (listen to clip), recorded in 1949, was a popular success; at his recitals, audiences hoped to hear the song as an encore bonus.

The German baritone Willi Domgraf-Fassbaender, the vocal model for the satanic Nick Shadow, will be unfamiliar to many. Prominent at the Stuttgart State Opera, he also had a long association with the Berlin State Opera, from 1930 to 1948. In 1949 he starred in a highly regarded German-language opera film, Figaros Hochzeit, made in what was then East Germany. Among his audio-only recordings, Guglielmo’s aria “Donne mie” (listen to clip) from Mozart’s Così fan tutte is full of lively wit. Perhaps less expected are his handsomely lyrical, sensitive interpretations of Hugo Wolf’s lied “Verschwiegene Liebe” (listen to clip) and Wolfram’s aria “O du, mein holder Abendstern” (listen to clip) from Wagner’s Tannhäuser. In all of these examples, Domgraf-Fassbaender’s baritone comes across as brighter, lighter, and more agile than the lugubrious, bass-heavy voices sometimes heard as Nick Shadow. His ideal Mozartian timbre would have helped make Shadow sound more like what Edward Mendelson calls that villain: “a Mephisto disguised as a Leporello.”

•

The choice of Ebe Stignani for Baba the Turk is the most enlightening. Kallman sets very specific terms: “Baba’s coloratura, conceived in terms of Stignani’s range and evenness of intonation, clearly characterizes her with the same uncaricaturized brio that we wished her words to convey.” Stignani was often thought of as a dark, heavy, “dramatic mezzo-soprano,” suitable for Verdi’s Amneris or Azucena (listen to clip) or Wagner’s Ortrud. But what Kallman praises is not her dramatic chest-voice heaviness but rather her agile coloratura, which she could execute high or low; she was in fact the more flexible “coloratura mezzo-soprano,” fit to sing, for instance, Zaida in Rossini’s The Turk in Italy, which she performed, or Rosina (listen to clip) in The Barber of Seville. For future reference, remember that she also sang the “trouser” role of Orfeo in Gluck’s Orfeo ed Euridice (listen to clip).

A handy Wikipedia page devoted to the mezzo-soprano voice, and clearly indebted to Richard Boldrey’s authoritative Guide to Operatic Roles and Arias (Caldwell, 1994), gives Baba the Turk as an example of the category “coloratura mezzo-soprano,” which it describes this way:

The coloratura mezzo-soprano has a warm lower register and an agile high register. The roles they sing often demand not only the use of the lower register but also leaps into the upper tessitura with highly ornamented, rapid passages. . . . What distinguishes these voices from being called sopranos is their extension into the lower register and warmer vocal quality. Although coloratura mezzo-sopranos have impressive and at times thrilling high notes, they are most comfortable singing in the middle of their range, rather than the top.

Many of the hero roles in the operas of Handel and Monteverdi, originally sung by male castrati, can be successfully sung today by coloratura mezzo-sopranos. Rossini demanded similar qualities for his comic heroines, and Vivaldi wrote roles frequently for this voice as well.

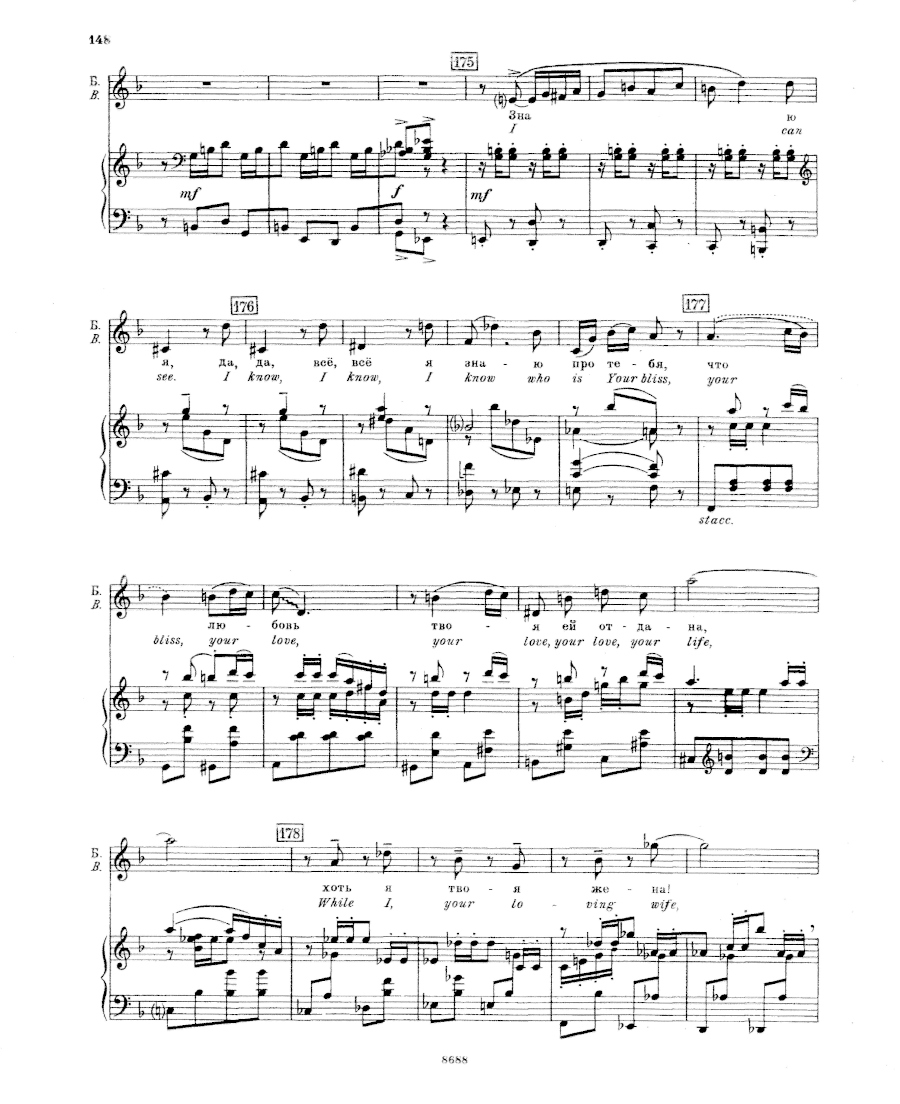

In composing for Baba, Stravinsky exploited the special qualities of this vocal category — “not only the use of the lower register but also leaps into the upper tessitura with highly ornamented, rapid passages.” The leaps from a strong lower register to high passagework, which Stignani handled “with ease of intonation,” are the very definition of what Baba must do in the often problematically staged Breakfast scene (Act II, Scene 3) and Auction scene (Act III, Scene 1) in The Rake. There, the singer must skillfully negotiate what voice teachers call the passaggio, in this case meaning the treacherous transition zone between the chest voice and the middle voice and, again, the danger zone between the middle voice and the head voice. Stignani managed the passaggio extremely well, but for merely mortal singers, an ugly break between registers always lurks as a danger.

Looking at Baba’s part in the vocal score, especially her jagged aria “Scorned! Abused!,” it can seem that Stravinsky’s writing deliberately makes it more difficult to manage the passaggio. In this clip, the role is sung by Kate Howden, who — under the direction of Barbara Hannigan — sails through relatively unscathed. But in less highly skilled hands, especially when the role is allowed to become a (dare I use the word?) travesty, the extreme stress on vocal agility can make seeming technical inadequacy part of the grotesquerie of the character. The wide, irregular intervallic leaps in this vocal line can undermine the credibility of the character when, as sometimes happens, Baba is cast as much for slapstick comedy as for superbly controlled coloratura singing. Encouraging audiences to respect the coloratura is a challenge that student singers have often been eager to take up.

An ordeal for mezzo-sopranos, the gratuitous strain inflicted on Baba’s passaggio by the “rage” music may imply that the role in some sense has another, differently abled, kind of vocal category at the back of its mind, one that could do what even mezzos cannot.

The character’s daunting “Scorned! Abused!,” pushing at the edges of capability, may reveal the creative team’s knowledge of an appropriately-equipped kind of voice that, once dominant on the London stage, no longer existed.

The London Opera World in Hogarth’s Rake

As mentioned earlier, many of the hero roles in the operas of Handel and Monteverdi, today often sung by coloratura mezzo-sopranos, were originally written with the voices of eunuchs in mind.

When Stravinsky saw Hogarth’s engravings of A Rake’s Progress at the Art Institute of Chicago in April 1947, he began to reimagine them as a series of scenes in a staged opera. Indeed, one of the most allusive of the engravings — plate 2, The Levée — displays rich operatic content.

The Yale Center for British Art website details the image’s features:

This plate shows the Rake, having just come into his fortune, adopting aristocratic habits. He is surrounded by hangers-on, including a fencing master, dance master, jockey, landscape gardener, and harpsichordist. The score on the music stand is a fictional opera, “The Rape of the Sabines,” in which the “ravishers” are played by well-known castrati and the “virgins” by scandal-laden sopranos. The scroll tumbling over the back of the harpsichordist’s chair lists gifts given to the visiting castrato Farinelli. . . . The print on the floor at the end of the scroll depicts Farinelli seated on a pedestal receiving the hearts of wealthy women, one of whom calls out “One God One Farinelli” — a direct quotation from an actual incident, and an example of the adoration Farinelli inspired in his audiences. The Italian opera is thus given a central role in the Rake’s downfall, standing for all that is decadent.

Decadent in more ways than one. The barbaric practice of castrating prepubescent male singers, generally from poor families (mostly in Italy) who were paid a fee, waned at the end of the eighteenth century, but of course was still very much in evidence in Hogarth’s time. London remained a center of Handel’s influence, where his Italian operas such as Giulio Cesare featured castrati in principal male-character roles, in this case both Cesare and Tolomeo.

On the continent, Mozart too wrote castrato roles, in as many as seven of his operas, from his early Mitridate, re di Ponto in 1770 to the late-career La clemenza di Tito in 1791.

The eighteenth-century London opera world, as seen in The Levée, may suggest how Stravinsky’s Rake, composed with Handel and Mozart in mind, alludes to singers like those.

•

Just to be clear about the vocal issues, an article in the medical journal Lancet explains the special mechanics of the castrato singer:

Removal of the testes results in the absence of male-type growth of the larynx. In the only recorded post-mortem examination of a castrato the dimensions of the larynx were strikingly small, with the vocal cords the length of a female high soprano. However, in a castrato somatic growth continued unhindered, resulting in a voice very different from that of the prepubertal boy. Although there was the high pitch of the child, soprano, or contralto, it was associated with fully grown resonating chambers provided by the pharynx and oral cavity as well as an adult thoracic capacity, made even more effective by intensive voice training. Yet although the pitch may have been similar to that of a female, the timbre of the voice was different. A contemporary critic described the castrato sound as being “as clear and penetrating as that of choirboys but a great deal louder with something dry and sour about it yet brilliant, light, full of impact.”

Like media megastars today, the great castrati singers of the eighteenth century were so famous as to be known simply by one-word names: Caffarelli (1710-1783), Cusanino (1704-1760), Pacchierotti (1740-1821), Senesino (1680-1759) — and, most especially, Farinelli (1705-1782), who figures conspicuously in Hogarth’s The Levée — were cultural superstars in London and throughout Europe.

Yet they also aroused a marked unease in some quarters.

For instance, in Tobias Smollet’s novel The Expedition of Humphry Clinker (1771), the character Lydia Melford describes a visit to the Ranelagh pleasure gardens, in Chelsea, and hearing the castrato Tenducci:

There I heard the famous Tenducci, a thing from Italy — it looks for all the world like a man, though they say it is not. The voice to be sure is neither man’s nor woman’s but it is more melodious than either; and it warbled so divinely that while I listened I really thought myself in paradise.

We know from such accounts that the leading castrati were treasured for their vocal pyrotechnics and haunting tone. But they were also sometimes mocked as anomalous stage presences, as Smollet’s calculated use of the terms “a thing” and “it” insinuates.

More bluntly, Roger Pickering wrote in Reflections upon Theatrical Expression in Tragedy (1755):

Farinelli drew every Body to the Haymarket. What a Pipe! What Modulation! What Extasy to the Ear! But, Heavens! What Clumsiness! What Stupidity! What Offence to the Eye!

Baba, too, possessed of an assertively distinctive individuality, can strike a nerve, as did the castrati clique of Hogarth’s era, by bodying forth an implicit challenge to the ruling binary gender-categories of their times.

With the crisscrossing identities in eighteenth-century London stage music, Auden and Kallman’s uncontrollable laughter at the birth of their Baba may have been triggered by all that is extravagantly overdetermined in this character.

Baba as a Countertenor

Amid the great reemergence of the countertenor as an admired vocal category, in 1999 the Chicago Tribune noted:

Countertenors, in short, have come a long, long way since the 1950s, when Alfred Deller, the British countertenor who put the breed on the map, found himself the subject of snide put-downs from male musicians at orchestra rehearsals. “I see we have the bearded lady singing tonight,” one concertmaster is supposed to have said.

In the TV film version of The Rake produced in Sweden in 1995, conducted by Esa-Pekka Salonen, the role of “the bearded lady” was indeed sung by a countertenor: the gifted Brian Asawa. (In a great loss to music, Asawa died in 2016 at the age of forty-nine.)

Alex Ross, in the New York Times, reviewed a wide-ranging recital by Asawa in 1994:

In a remarkable recital on Monday night at the Walter Reade Theater, Brian Asawa showed the kind of pure, effortless countertenor voice that comes along only once in a long while. It is hard to convey the uncanny effect of his full, fluid, lustrous tone, poised in the extreme upper register without the slightest strain. Close your eyes for a moment, and you would think you were hearing a mezzo-soprano.

Mr. Asawa sang not only with great technical assurance but with substantial and versatile musical understanding. . . . His ventures into 20th-century music hold particular interest; although modern operatic roles for countertenors are few and far between (Oberon in Britten’s Midsummer Night’s Dream is the major one), a singer of this magnitude might cause all that to change.

The next year, Asawa appeared in the TV film of The Rake’s Progress.

Although the Rake film from Sweden is not without flaws, director Inger Åby does creatively encourage us to rethink the opera’s private allegory, especially with respect to Baba the Turk. In his assumption of the role, Asawa, with his trim goatee, makes it clear that this is indeed a male singer — portraying a character who is in fact in this instance not a woman but a man. (This production, as it happens, appeared a couple of years after Neil Jordan’s acclaimed film The Crying Game, with its famous “reveal.”)

Åby’s direction carefully prepares for the beard reveal. Notably, in the Brothel scene (Act I, Scene 2), while the sex workers start to undress Tom, for a moment they fit him out with the madam’s own black-lace corset. About to initiate him into the world of carnal joy, they nonetheless see in him a kind of prettiness that renders the corset not entirely a joke. As performed here, this may be among the most melancholy, introspective orgy scenes in the operatic repertoire (watch clip), with Tom lingering over the words “my sorrow and my shame.”

Baba’s entrance scene (Act II, Scene 2) is just as carefully constructed. On screen, in relatively tight shots, the trio — with Greg Fedderly (Tom), Barbara Hendricks (Anne), and Asawa (Baba) — plays out with an emotional intimacy difficult to achieve on stage (watch clip). The saraband closing out the scene culminates in a tableau of exceptional tenderness. After removing the veil, revealing the tidy goatee (far from the Assyrian prototype), Baba goes on to gently, sensuously, remove Tom’s powdered wig. The close-up camera shows how these “intimate revelations” bring both of them to near-ecstasy: Tom, for once not the self-centered cipher he seems to be elsewhere in the opera, learns what it means to fall unexpectedly, helplessly in love. At least for a while.

Not everyone found the production convincing on this score. David Schiff wrote in The Atlantic:

. . . there has always been confusion about whether Baba is supposed to be a woman or a man. Last year the Public Broadcasting System showed a Swedish movie of The Rake’s Progress in which Baba was clearly a man, sung by a male alto with a short goatee. Instead of solving the problem, the TV movie just showed that in our enlightened age a drag queen is less threatening than a woman with a beard — and proved that Baba makes no sense at all as a cross-dressed man.

Whatever the personal sources of the character may have been, I think that Baba was Auden’s way of embodying his love for the genre of opera in all its glorious absurdity. Baba breathes the spirit of opera itself — for she is nothing less — into the dead bones of The Rake. She throws the whole tidy moral universe of The Rake into confusion by showing us how dull it has grown. Morality is fine, she seems to say, but could we have some entertainment, please? And not a moment too soon. She seizes the stage in an ascending series of coups: a grand entrance, a funny patter song, and, before her grand exit, a breathtaking moment of compassion and renunciation that would have made Hugo von Hofmannsthal, who could well have been Auden’s model as a librettist, weep with pleasure.

Baba was Auden’s joker in the pack, his way of trumping his own moral pessimism by asserting the power of art over nature.

Still, one might reply, if Baba’s role is to “throw the whole tidy moral universe of The Rake into confusion,” what better way to challenge it than by taking the beard quite literally, as a marker of Baba’s true sexual identity, and see what happens when, to repeat the prologue’s implication, a “She” is displaced by a “He.”

•

Of course this pronoun usage, second nature to the librettists as they wrote in the late 1940s, reflects the now increasingly remote era when the gendered pronouns she and he stood unchallenged. To many today, these ever-present parts of speech (along with their possessives, her and his) have the effect of enforcing an outmoded binary system. Acknowledging how our language changes, in 2019 the Merriam-Webster online dictionary chose as its “Word of the Year” the pronoun they. The dictionary’s team described the innovative new sense that earned the word’s recognition: “Used to refer to a single person whose gender is intentionally not revealed, or — Used to refer to a single person whose gender identity is nonbinary.”

Auden and Kallman were no longer around to witness the shift to they. But in creating Baba the Turk, they did help expose the inadequacy of the binary terms she and he. Their prologue’s rhyming throwaway line, evading a specific term, says instead “you’ll see.” The Swedish film capitalizes on that, and follows through with what you will indeed see.

•

Another critic of the Rake film found the countertenor’s casting untroubling, but also unauthorized. Martin Bernheimer wrote in the Los Angeles Times:

The only controversial casting involves Brian Asawa, a youthful countertenor assigned the flourishes of Baba, the bearded lady whom Tom marries (a role Stravinsky intended for a mezzo-soprano in the manner of Ebe Stignani). Asawa sings with astonishing purity of tone, steadfastly avoids all hint of caricature and stresses sensuality without even attempting a female impersonation. Although the homoerotic impulses that result make a certain kind of ironic sense in context, it isn’t the sense the composer had in mind.

Whether or not it’s the sense the composer had in mind, is it a sense that perhaps the librettists could have had in mind? When Bernheimer observes that Asawa “steadfastly avoids all hint of caricature,” the critic shows how the countertenor meets Kallman’s defining requirement for a Baba singer: “uncaricaturized brio.”

Since then, other countertenors have taken the role. For instance, in the 2017 Aix-en-Provence Festival production (watch video), Andrew Watts sang Baba, though to different effect.

•

Where does Baba the Turk wind up in the critics’ appraisal of who’s who in The Rake?

As noted at the outset, in reading the libretto allegorically, Auden can be seen in Anne, loving and faithful, while Kallman plays the wandering, promiscuous Tom. Edward Mendelson, in turn, highlighted the underlying allegory of Baba as Auden the artist.

But other permutations are certainly possible. For example, Sascha Bru has argued that “Baba may refer to Sheilah Richardson, in whom Auden thought he had found the means to ‘free’ himself from his homosexuality when he proposed to marry her.” In the opera, Baba quickly flees from the role of spouse and goes back to the circus.

Following up on that, here’s another possibility in the shifting permutations of who’s who: perhaps Auden can be thought of, in just the Baba episodes, as Tom — who, like Auden himself, rashly acquired a high-spirited, theatrical life partner he could never hope to control.

This improbable multiplicity of meanings surrounding a bearded lady may be counted among Matthew Aucoin’s paradoxical “impossibilities” in opera.

Unlike the new usage of the word beard that became common in the 1970s, the beard in The Rake’s Progress actually reveals, rather than disguises, the true identity of its creators.

(June 2022)